Tracing Arte Povera and Pop Art through film

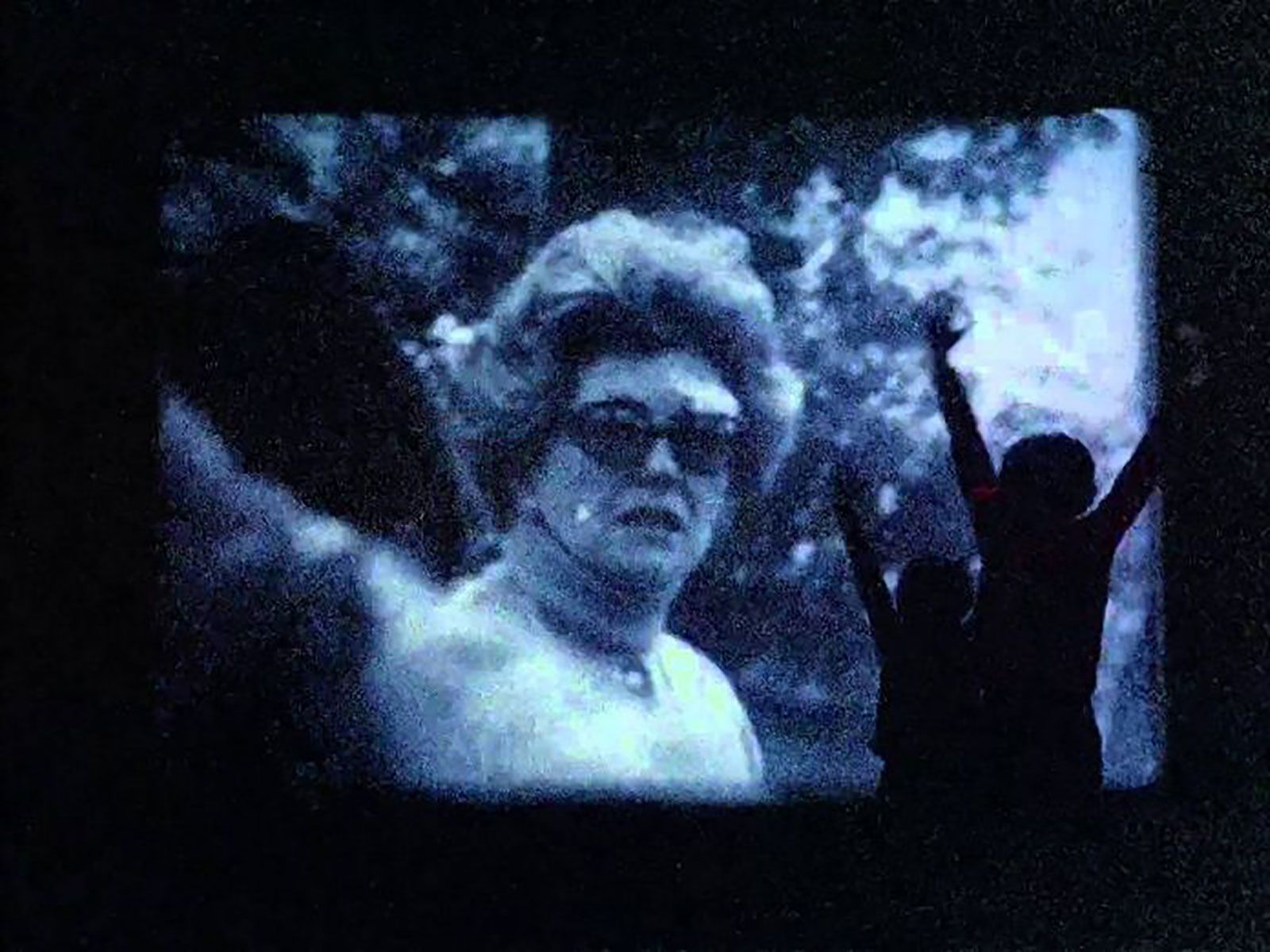

Mario Schifano, Umano non Umano.

As the subject of much scholarly discussion, ties between visual arts and cinema or film are saturated in decades of artistic experimentation. In the early 1960s in Italy, visual artists such as Michelangelo Pistoletto, Mario Merz, Marinella Pirelli and Mario Schifano were heavily involved in experimental film making. “The New American Cinema” group highly influenced the art scene in Rome and Turin, informed through Italy’s Neoavanguardia, history of experimental film traced through Futurist cinema and the subsequent role of propaganda film during fascist rule. Experimental cinema during the late 1960s became an intermediary format joining the Zeitgeist of Pop Art with the present aesthetics and materialism of Arte Povera in an unusual yet intense artistic dialogue.

Post-War Italy experienced “il boom economico”, an economic boom that was particularly dominant in the late 1950s to mid-1960s. While this strong economic growth brought prosperity to a mostly poor and rural country, the boom moreover reconstructed Italian’s society and culture. Transformed into an industrial state that could perform competitively on the global stage, Italian’s main cultural export became what is known as “La Dolce Vita”, the sweet life. Following the physical and moral devastation of the war and decades of reigning fascism, a strong economy prompted fundamental cultural and anthropological shifts in Italian society. These were primarily triggered by the emergence of capitalism, promoting a liberated modern way of life that advertised a vibrant lifestyle for the middle class. Born was an entertainment industry competitive with the rivalling American Hollywood machine. Rome’s “Cinecittà Studios” became the hub of Italian film production, establishing a strong mainstream film culture that was naturally met with efforts to challenge and subvert. The radical cultural shift of the late 1950s can only be compared to the activities of the Italian Futurists at the turn of the century, prompting an unparalleled desire to expand artistic expression. The performative, as the ultimate vehicle of individual expression, entered multiple art formats: music, theatre, poetry and ultimately the visual arts.

The European emergence of experimental cinema was greatly intensified through the developments overseas. Experimental film in the US was radically informed by both politics and a flourishing underground scene. Throughout Europe, art festivals and events began screening and hosting American performance art, such as the collective “The Living Theatre”. The group performed increasingly during the early 1960s in Italy where some of their most acclaimed theatric works were created. Works such as Bertolt Brecht’s “Antigone of Sophocles” (1967) or “Mysteries and Smaller Pieces” (1964) defined essential conceptual strategies promoting the rejection of the stage and ultimately eliminating set boundaries between art and life, identity and reality. Fundamental to the group’s practice was the concept of media, a rejection of traditional media, embracing the body as an intermediary form of ultimate human expression. Another American collective that appeared in the Italian art scene during the time was the “New American Cinema” (NAC), a group of independent filmmakers that began producing counter- culture films in the late 1950s. The NAC school included household names of American experimental film such as Kenneth Anger or Jonas Mekas. These filmmakers confronted audiences with radical subversions and abstractions of iconography referencing history, pop culture and in Anger’s case, an extreme obsession with sexuality. Demonstrating the potential of ultimate expression through film, it is argued that these American cultures highly influenced the organisational structures of film collectives in Italy. While the style and aesthetics of Italian experimental cinema strongly differed from the creations of the American counter figures, its institutional and organisational character prompted the emergence of similarly formed groups and collectives across various artistic hubs.

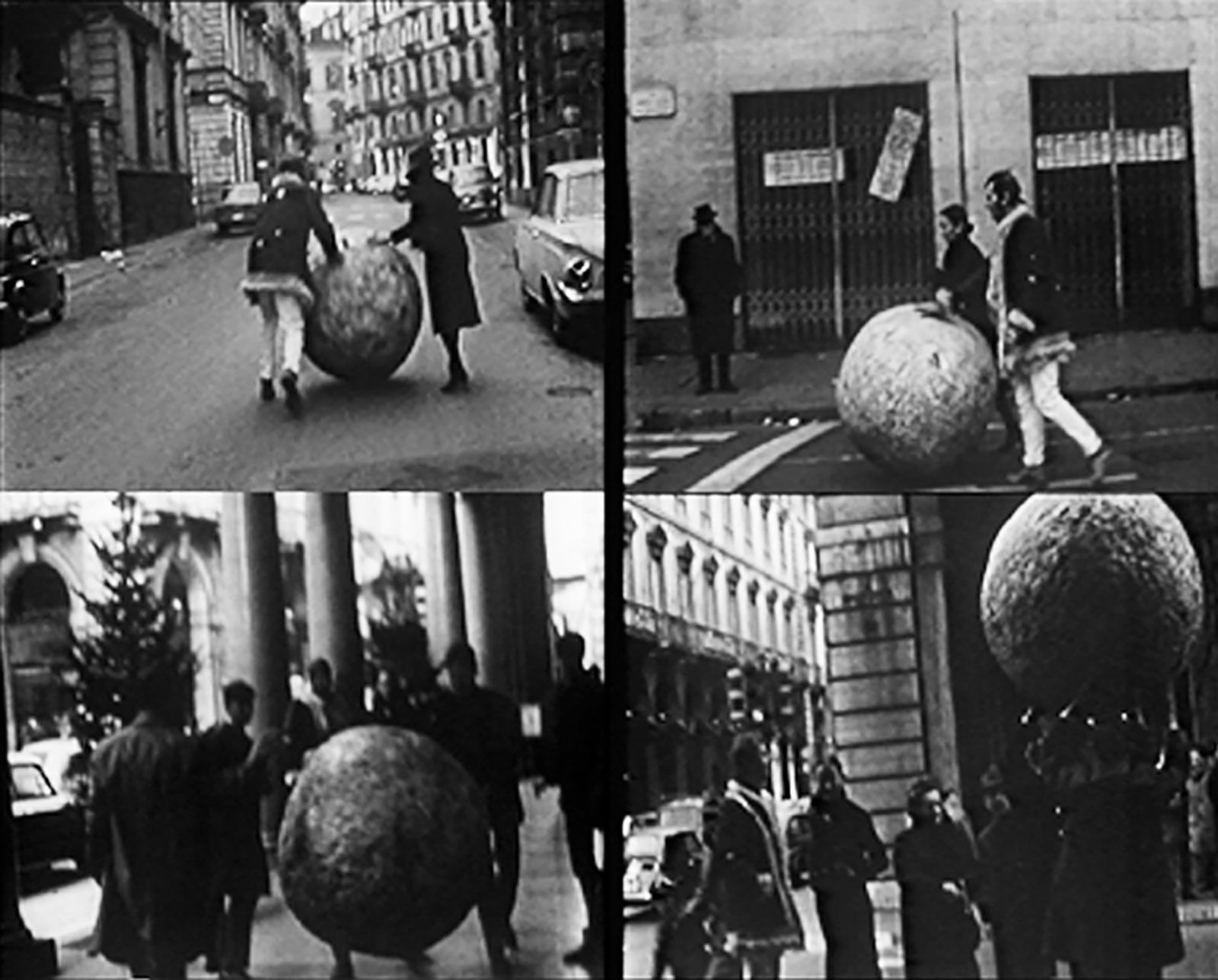

Excerpt from the film BUONGIORNO MICHELANGELO/ GOOD MORNING, MICHELANGELO, 1968 by Ugo Nespolo

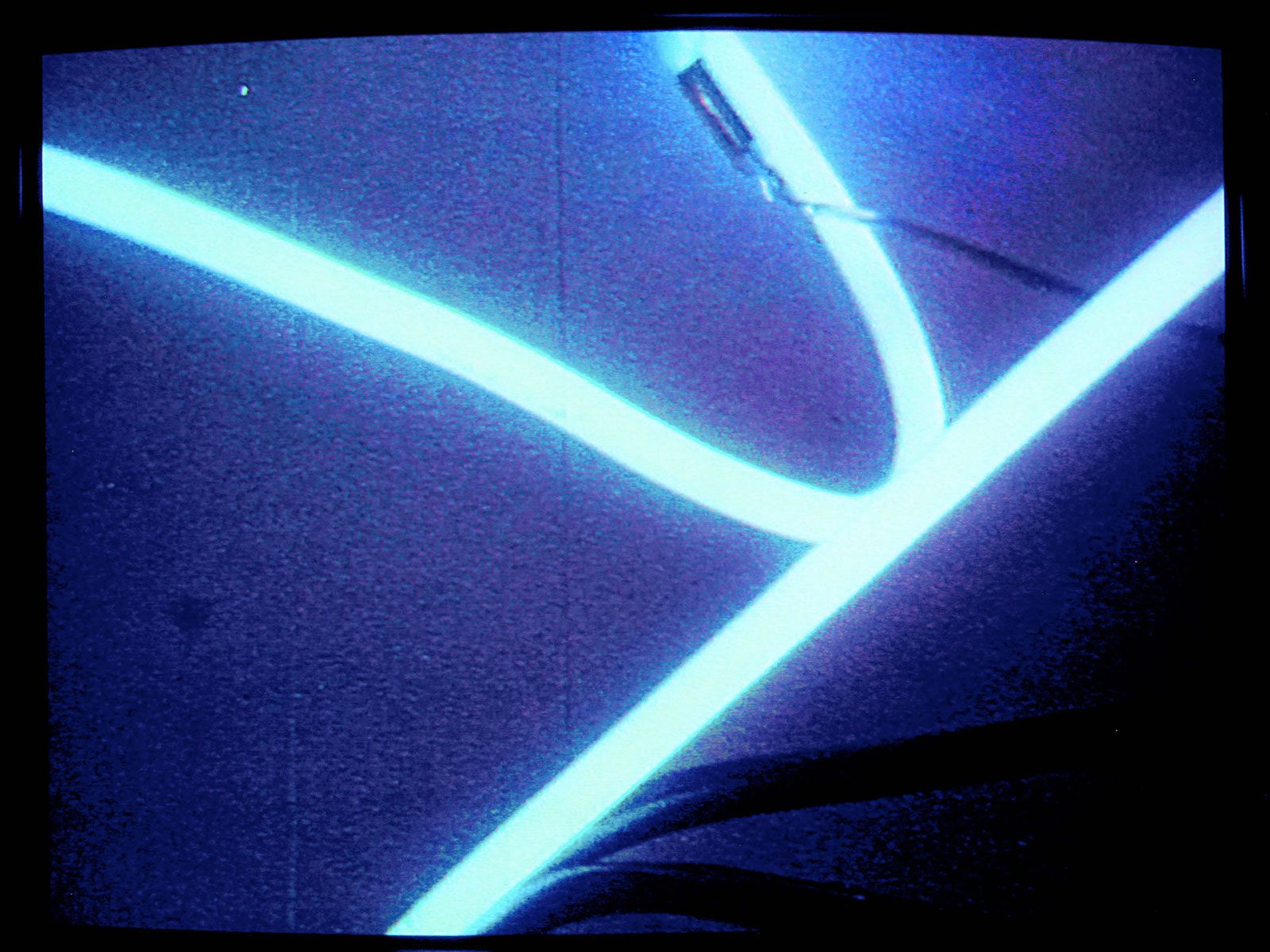

In Turin, artist Michelangelo Pistoletto’s practice became the focus of the films by artist Ugo Nespolo, whose painting and sculptural practice was influenced by an array of art movements of the time. Nespolo, however, remains particularly acclaimed for his experimental cinema works in which he often featured his friends and peers such as Lucio Fontana, Enrico Baj and in particular, Pistoletto. Films such as “Buongiorno Michelangelo/ Good Morning, Michelangelo” (1968) follows the artist as he takes his artwork to the streets in a performative, yet playful nature, rolling a ball of newspapers “La rosa bruciata” (1965) out of the gallery of “Christian Stein” along the roads of the city. Working with artist Mario Merz, Nespolo also directed the film “Neonmerzare” (1967), documenting a light tube installation at the gallery of “Gian Enzo Sperone” in Turin. This film perfectly exemplified the juxtaposition of documentary film making and abstract non-narrative aesthetics mirroring the subjects on display. In this same sense, Nespolo also worked with Alighiero Boetti, who at the age of 27 had a solo exhibition at the gallery Christian Stein, where the director documents the work on display extensively before abruptly introducing the audience’s reaction to the artwork.

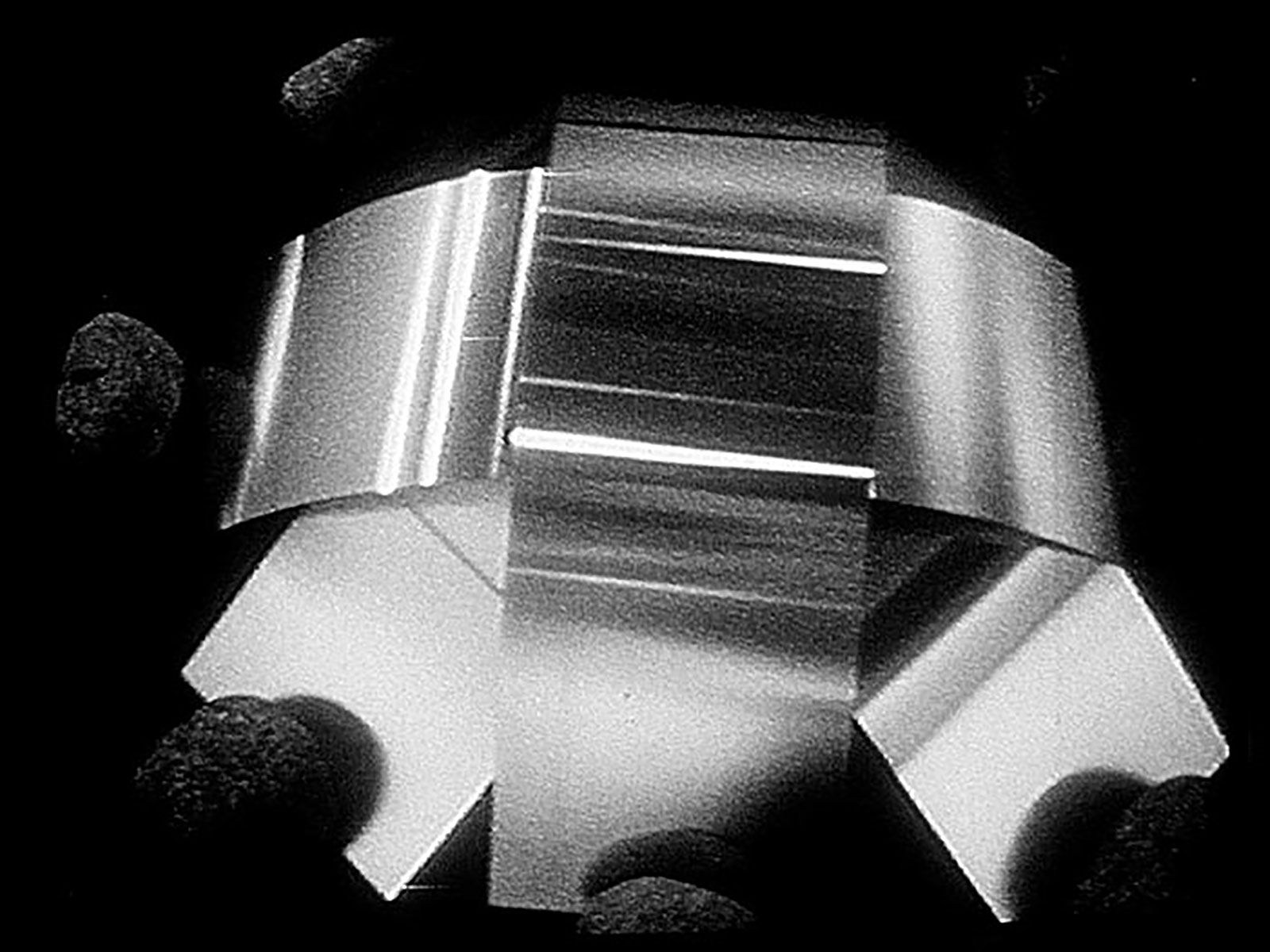

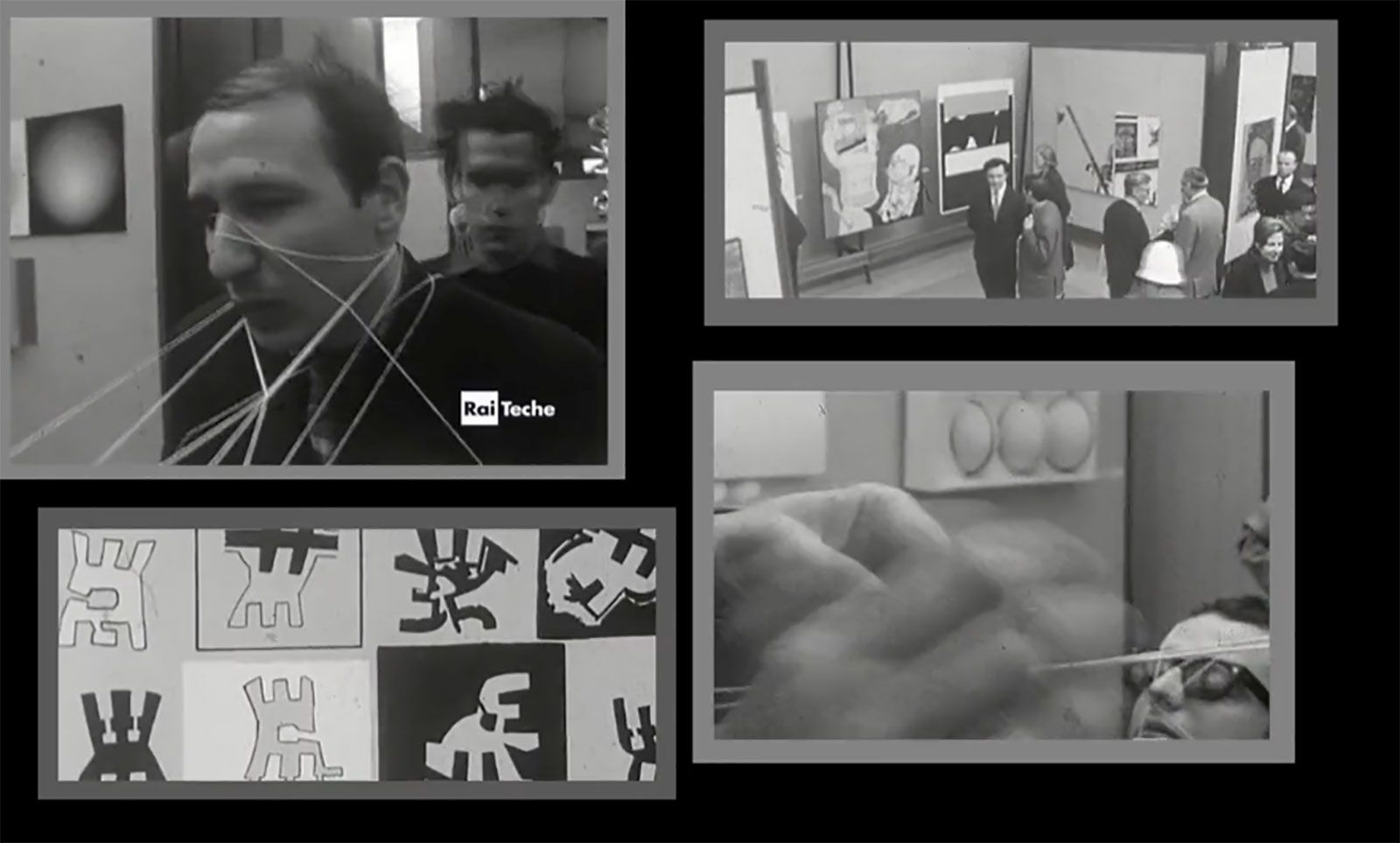

Stills from Ugo Nespolo’s BOETTINBIANCHENERO, 1968.

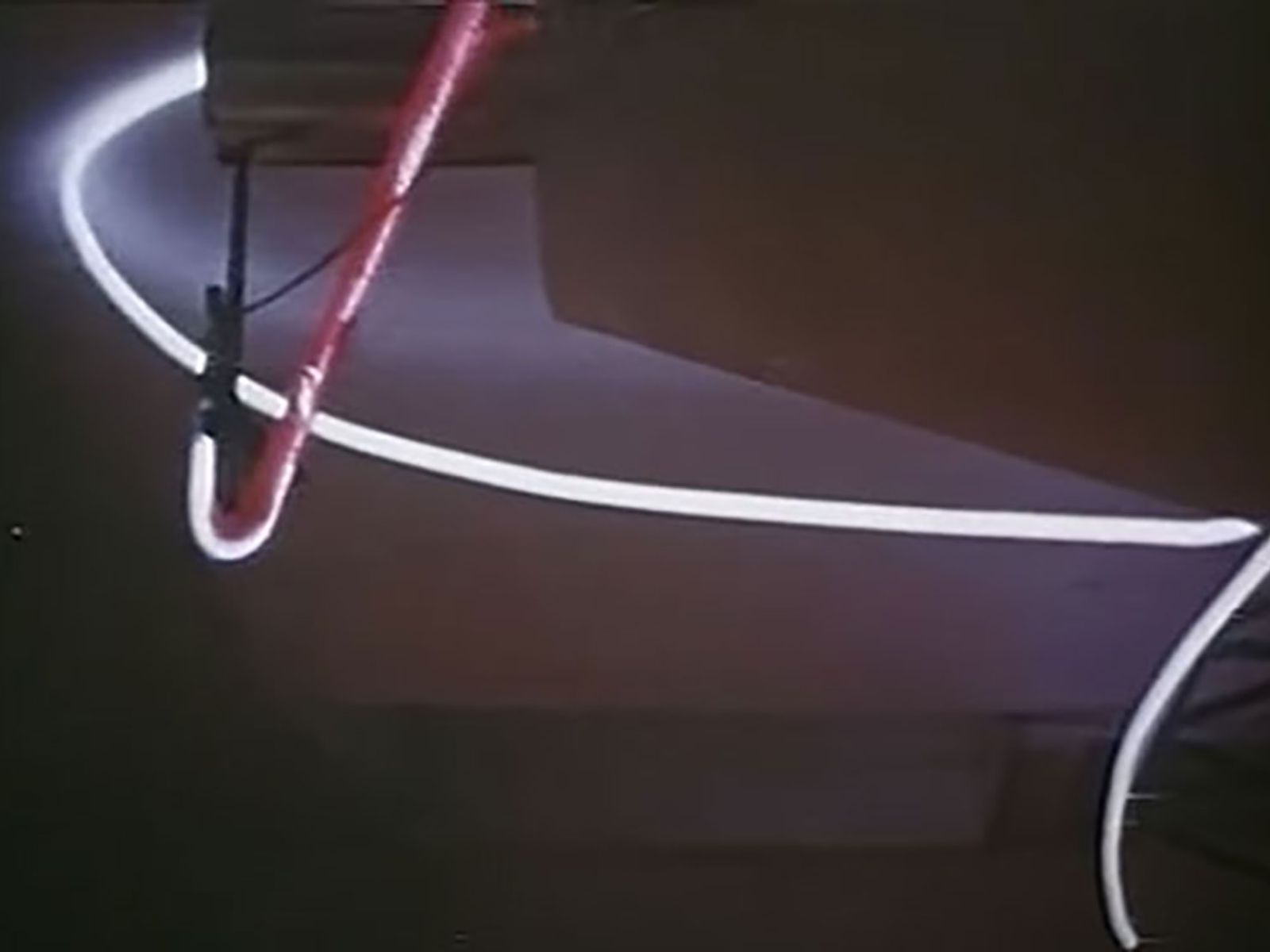

Still from Ugo Nespolo’s Neonmerzare, 1967.

Stills from Ugo Nespolo’s BOETTINBIANCHENERO, 1968.

Still from Ugo Nespolo’s Neonmerzare, 1967.

Ugo Nespolo’s Performance Fluxus at GAM Torino, 1967.

In “Pistoletto & Sothebys” (1968), filmmaker Pia Epremian recorded Pistoletto and his daughters Cristina and Maria Pioppi as they perform figures such as Edgar Degas, Vincent Van Gogh or Orpheus and Eurydice. Filmed at the artist’s studio space the characters engaged in the performance of short scenes acting and reenacting in front of a visual backdrop featuring an array of referential material such as photos depicting pop culture iconography. The audio playing was a mixture of random vocal sounds ranging from the piano sounds to simply noise. Epremian was an essential figure within this historical contextualisation as one of the only female filmmakers. As so-called “first-person cinema”, her practice specifically highlighted the predominate cinematic nature of these experimental films that focussed on the production and artistic experimentation of the time.

One of the only female artists working with video and formats of experimental cinema at the time was Marinella Pirelli. Her wide-spanning practice remained arguably uncharted, but her presence within the local art milieu in both Rome and Milan amongst the prominent Arte Povera artists of the time left a significant mark in the avant-garde scene. Trained as an illustrator, Pirelli worked in visual merchandising and the graphics during the late 1940s in Milan. Designing costumes for the local theatre “Il Carrozone”, the artist begins seeking the world of cinema flourishing at the time in Rome. Relocating to the capital in 1950, Pirelli began immersing herself in the world of Italian cinema, befriending screenwriters such as Ugo Pirro, Franco Solinas and Rodolfo Sonego. A year later she began working as designer for the film production house “Filmeco” producing animated advertisements. In the following decades Pirelli intensified her personal studio practice and finds herself amongst Mario Merz, Jannis Kounellis and other pioneering conceptual artists of the time. During these years she increasingly dedicated herself to the medium and format of the cinema. Pirelli’s experimental film practice concerned itself with environments, the body, the gaze and with cinema as apparatus itself, while experimenting with the boundaries of space and light.

“I was three years old when I realised I could remember: for example the birth of my sister, fourteen months younger then me. And later on, recalling this very moment I said to myself: ‘If I remembered, then I also must have had had conscious thought.’ And so I said: ‘I will memorise it’, and I was doing this with all sorts of things that were capturing my attention (flowers, lights, colours, people, gestures, sensations). That’s because I wanted that every present moment was total; me always as a whole of all the things that I was and knew, plus the new moment, to not loose anything, always knowing that every single thing is transitory, lost, over, immediately dead, or better, different. So here is the adventure: the making of a thought, the approaching of the day, the entering of the darkness.” (Marinella Pirelli, 1966)

In Rome, artist and filmmakers such as Franco Angeli, Luca Patella, Pino Pascali and Mario Schifano were more directly informed by Pop-Art influences. From 1967 to 1970, a short yet intense period, the “Cooperativa Cinema Indipendente”, “Cinema Co-operative” emerged as an organisation producing the largest amount of films of this style during the year 1968. Based on “The New American Cinema Group”, the group operated amid the visual arts, holding screenings and productions at Roman art galleries such as “La Tartaruga” of Plinio De Martiis and “L’Attico” of Fabio Sargentini. Amongst the many professionally educated emerging filmmakers, visual artists such as Mario Schifano appropriated this type of film making as an extension to his painterly practice. At a certain moment in time, the artist contemplated giving up painting entirely in favour of cinema. Considered as one of the important representatives of Italian Pop-Art, Schifano’s paintings were as concerned as much with iconography and political properties of imagery as one could argue Italian cinema was at the time. His film works “Souvenir” (1967) and “Anna” (1967-70) were specifically saturated with Pop-Art type imagery, while works such as “Vietnam” (1967) explicitly references the Vietnam war utilising found anti- imperialist footage.

The Rome school revealed itself to be critical of mass media’s intrusion in our daily life, confronting the media’s juxtaposition of violence and capitalism. While these subjects were highly informed by the themes emerging through Pop-Art, many of these experimental films produced by visual artists focussed on materiality and production, a pure practice of Arte Povera. Although the presence of consumer culture through imagery and commentary remained present, these productions did not result from Pop-Artists wanting to encode related signifiers. Instead, they documented the lives of artists left alienated and exploited as a consequence of the growing consumer culture.

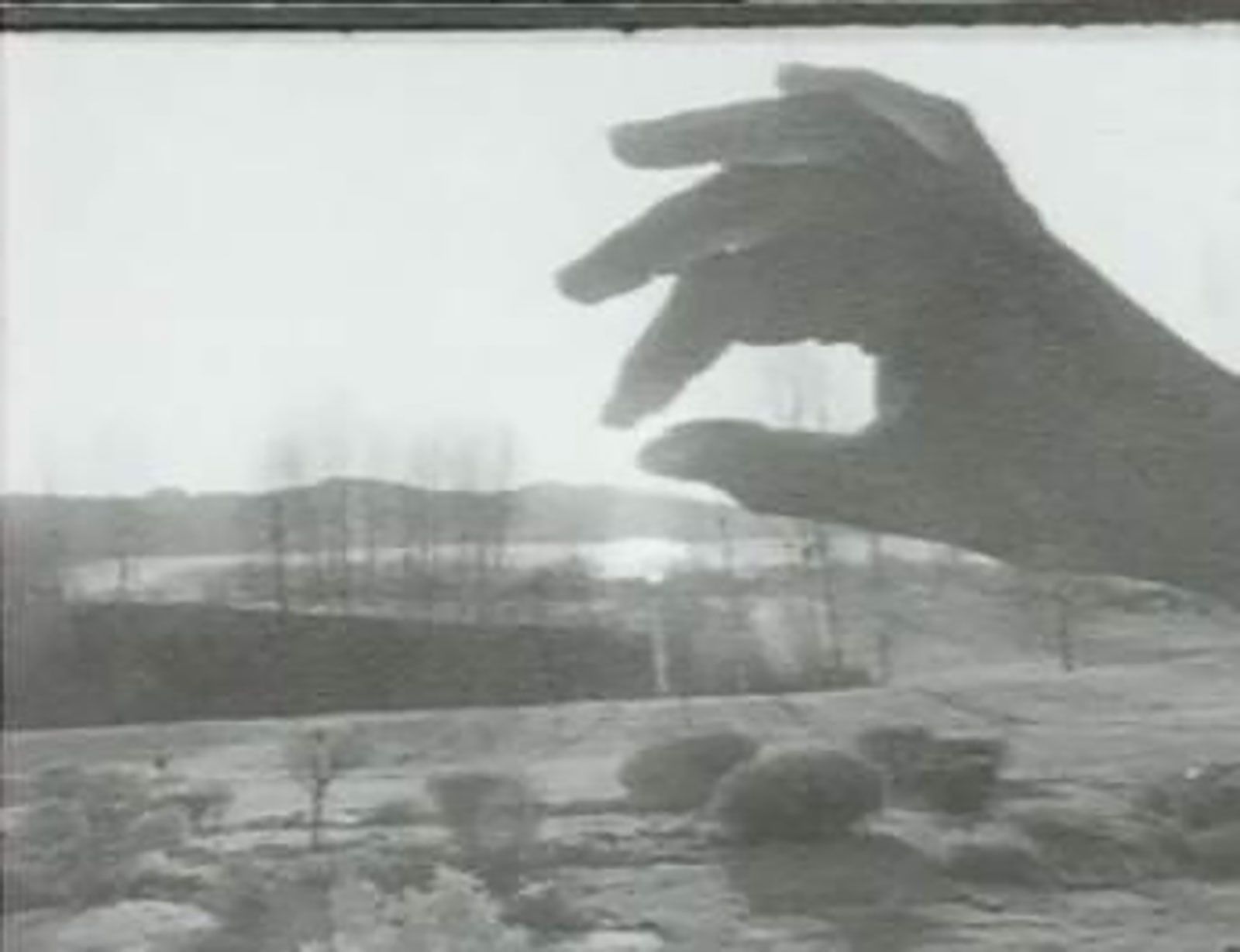

Marinella Pirelli at work.

Marinella Pirelli, Appropriazione A propria azione Azione propria, 1973. Courtesy Archivio Marinella Pirelli, Varese.