Pop Art: Aesthetics of consumption

“American Supermarket” at Bianchini Gallery in 1964.

The “American Supermarket” at the Bianchini Gallery in 1964 celebrated a pivotal moment in art history. At first sight, the space seemed to have been transformed into a supermarket. However, in reality, it was an exhibition showing the works of several Pop artists such as Robert Watts, Tom Wesselmann, Claes Oldenburg and Andy Warhol. As one of the first exhibitions that confronted the public with Pop art and the eternal question of: “What is art?”, it further introduced new icons. The appropriation of commercial imagery such as logos and advertising language represented a rapidly growing consumer culture and at the same time illustrated the vulnerability of a seemingly affluent capitalistic society in times of global distress.

When Mimmo Rotella started to tear down posters in the streets of Post-war Rome in 1953, the artist invaded a space that had been radically transformed since the war. A space where previously news bulletins and reports from the war were made accessible to Rome’s citizens, the rapid economic expansion introduced a new type of media and consumer culture to the public space. Rotella became fascinated with the presence of vibrant imagery ranging from film advertisements to the promotion of household consumer products. Similar to the “Affichistes” in France, a movement that Rotella is often associated with, the artist aimed to present a new reality reflecting the dreamy landscape of the city and urban life. At the time, a radical intervention as a counter medium to painting, these artistic activities of the early 1950s have been credited as trailblazing, foreshadowing Pop art and Street art.

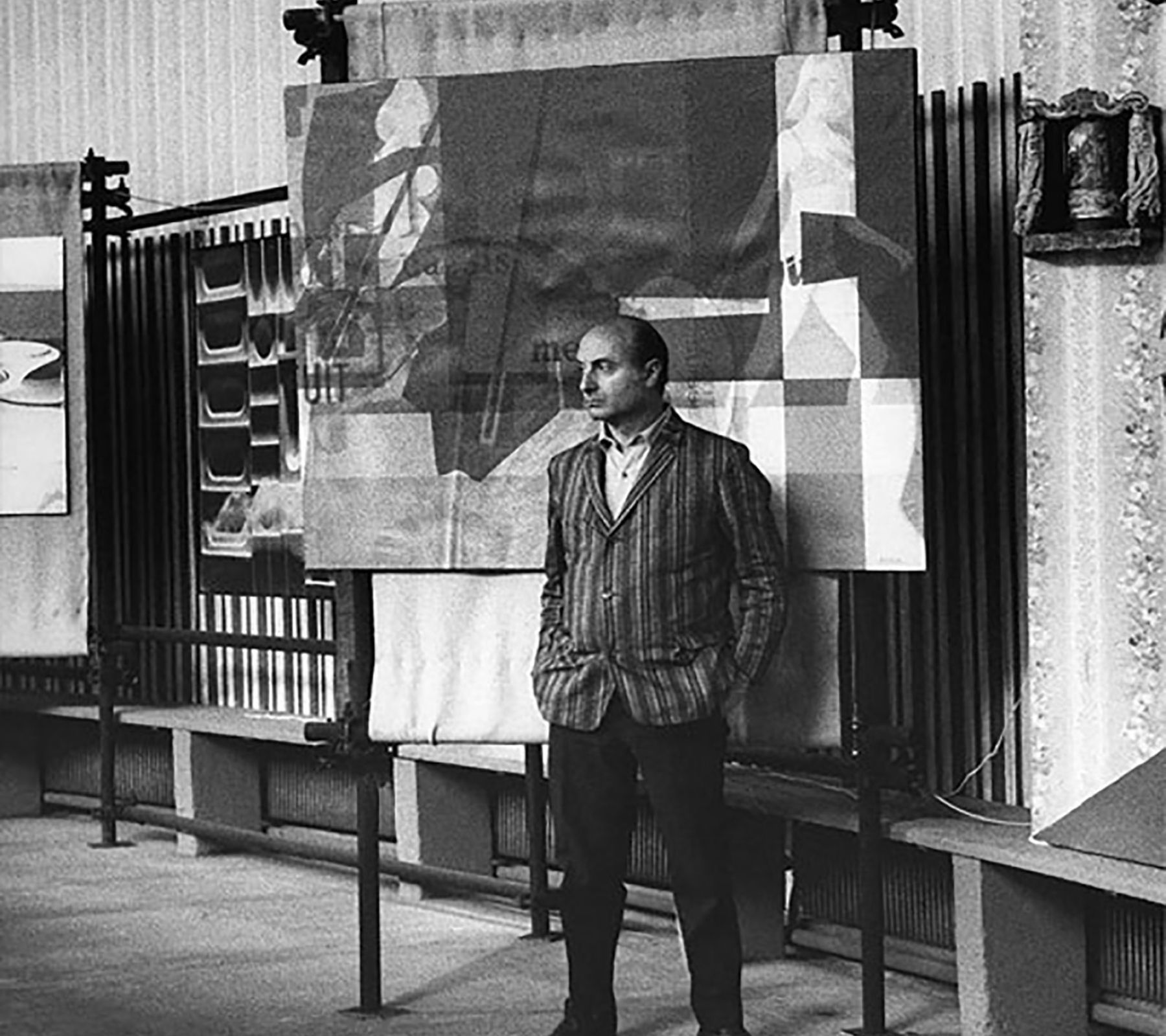

Mimmo Rotella in front of an Artypo in 1967.

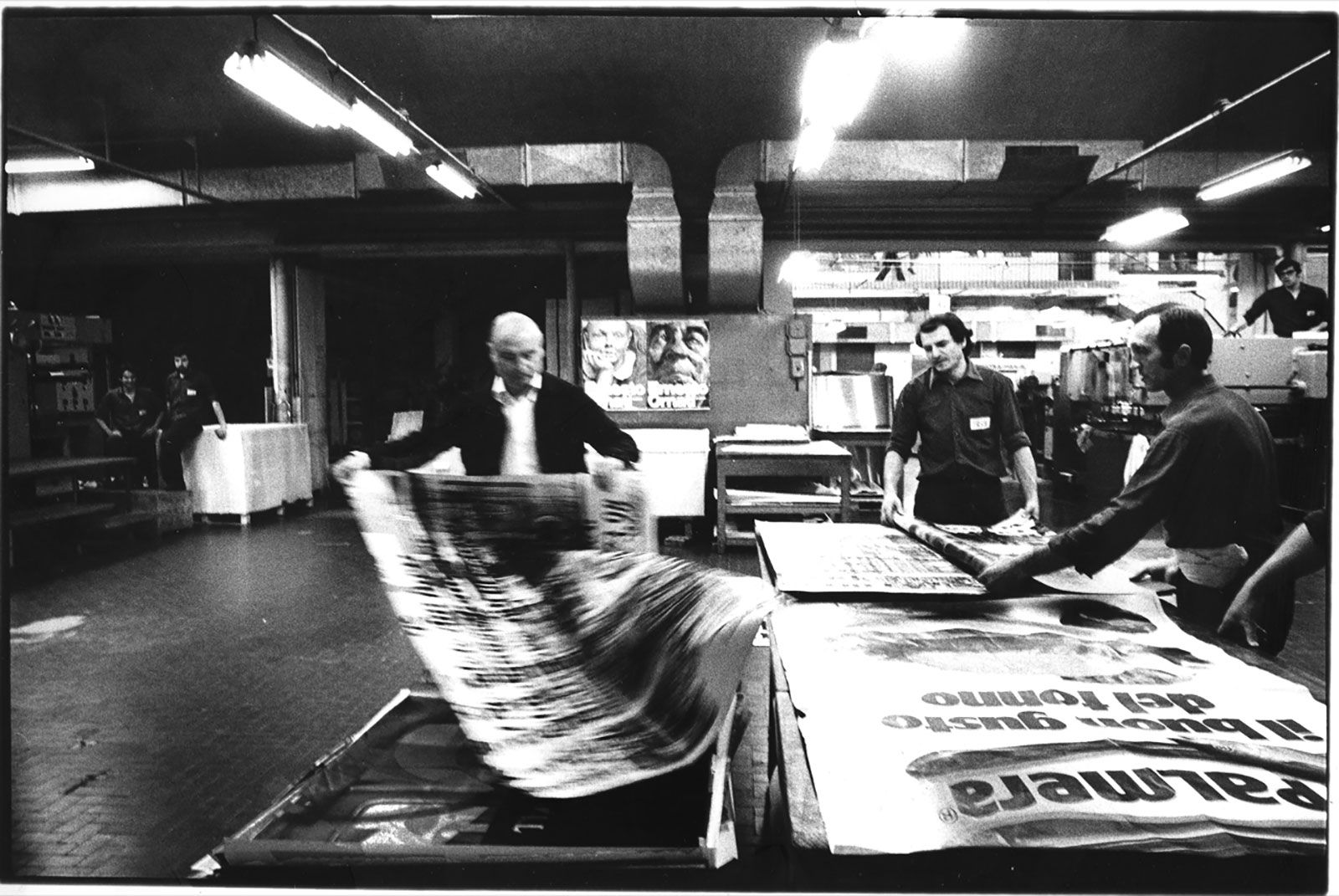

Mimmo Rotella in 1975 at the printer shop.

While the production of the décollages, fragments of layered and torn posters applied to canvas, made Rotella famous during these years, the artist sought a new technique in the early 1960s. Art critic Pierre Restany recalled that the artist showed him his first “reportages”, photo emulsions, in 1963. There is not much known about what might have triggered Rotella to explore a new medium. He is quoted to have said: “I felt the need for renewal, for the discovery of something new, and out of this came the reportage.” The technique of the photo emulsion offered the artist a unique representation of the subjects he was interested in. Within art history, we find ourselves at the very beginnings of Mec-Art, another movement that Rotella was a leading figure of. Mechanical art production and the parallel developments of New Dada, Nouveau Réalisme and Pop-art represented an evolution in the arts which introduced a new visual language sourced from advertising and the mass production of consumer goods. Rotella’s photo emulsions allowed the artist to depict reality in the most direct form to photographic transfer, emulsified on canvas. The subjects captured are countless images ranging from film, popular culture, politics, religion to adverts. They all share a common factor, recognisability.

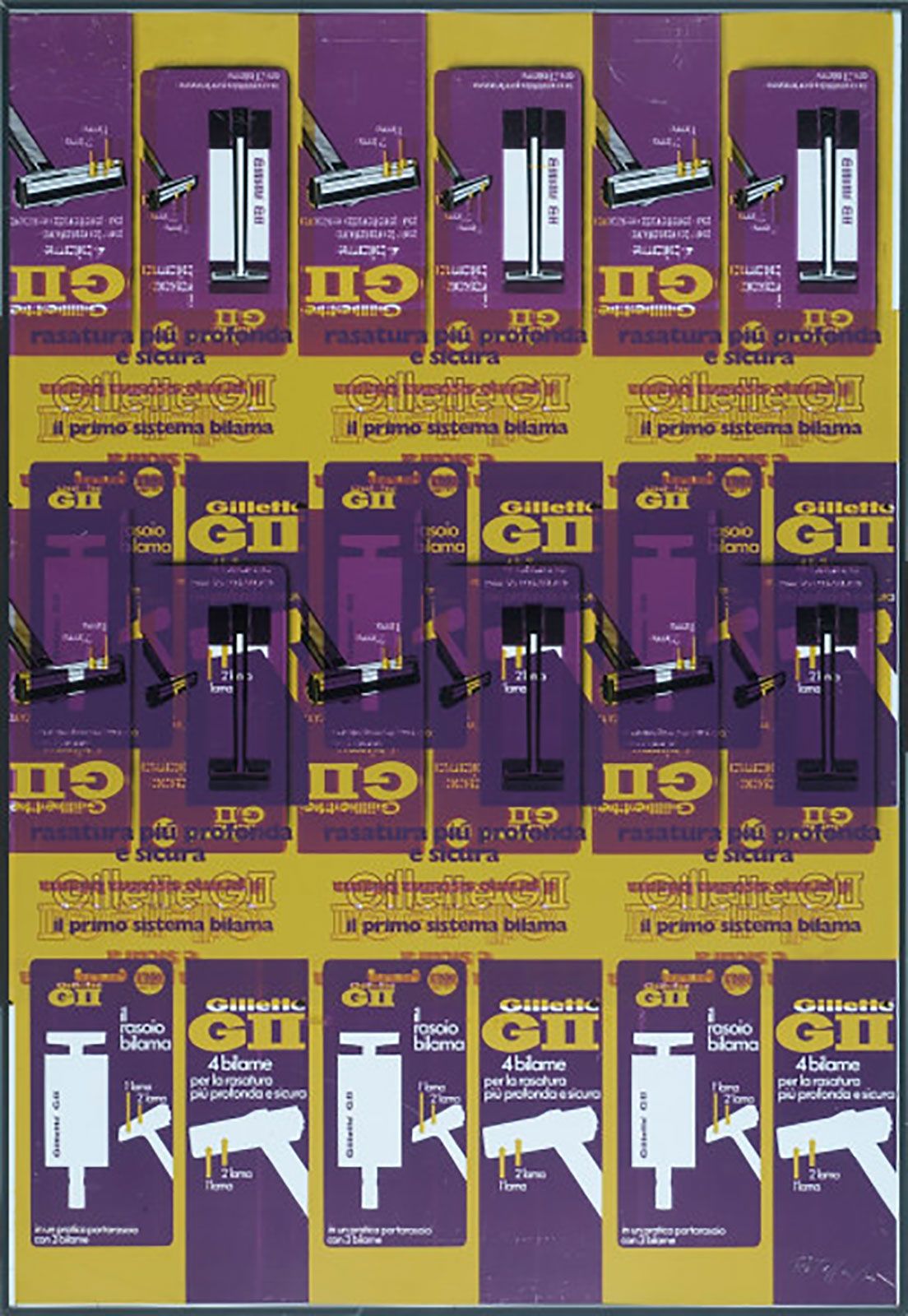

With the development of the artypo in 1965, Rotella discovered another technique that would further assert his place within the Mec-Art movement in Europe. In contrast to the photo emulsions, this practice directly appropriated the printing proof sheets utilised at the commercial printers for the production of street advertisements. Reducing the artistic intervention to a minimum, Rotella produced directly from the distributive source of consumer culture. In Rotella’s artypos, several stylistic elements play a vital role in evoking the commercial properties present in the mid 20th Century. Repetition, reproducibility and recognition were all formal elements that the artist appropriated within the compositions. Some of the works juxtaposed several different image sources creating new meaning and space for interpretation. Often single fragments are isolated and centred on the surface of the works, other times the back of the artypo will reveal a layer not visible on the front of the work at all.

Mimmo Rotella, Bilama, 1975.

Mimmo Rotella, Brindisi, 1966.

Ranging from a complete abstraction of adverts to the full representation of logos and typography the artypos explore the landscape of advertisement and consumer manipulation that the public was arguably more aware of at the time. Here Rotella played with the iconography the artist was very well known for through his décollages which presented films icons of the time such as Marilyn Monroe. With the artypo however the signifiers became less dominant and hierarchies between image and meaning vanished, fully realising a pure and neutral realisation of an art “object”. Restany defined this body of work as “ready-made sur-image”, that through the actions of appropriating existing imagery created its own “super-image”. The art critic also referred to Rotella as “the first purely plastic artist in contemporary printing”. In this essence, the artypos reflected the spirit of the time, reflecting a new “plastic” aesthetic, mirroring consumer society.

Meanwhile, in the Us, Andy Warhol, leading figure of the Pop-Art movement, rose to fame with the appropriations of popular icons such as Marilyn Monroe and consumer icons such as Campbell soup as seen is his famous “Campbell’s Soup Cans” series. His practice was strongly linked to advertisement and consumerism. In 1949 when Warhol firstly arrived in New York, he began working as a visual merchandiser, illustrator for magazines and books including Vogue, Seventeen and Glamour magazine. Starting in 1952, the artists who had previously exhibited drawings begins experimenting with techniques associated with the commercial industry, such as photo-static machines. Working as a commercial artist, Warhol implemented early artistic approaches monetising his private practice such as publishing promotional catalogues for clients and eventually in 1957 established “Andy Warhol Enterprises, Inc”.

“The new art is really a business. We want to sell shares of our company on the stock market”.

Andy Warhol, Campbell’s Soup Cans, 1962.

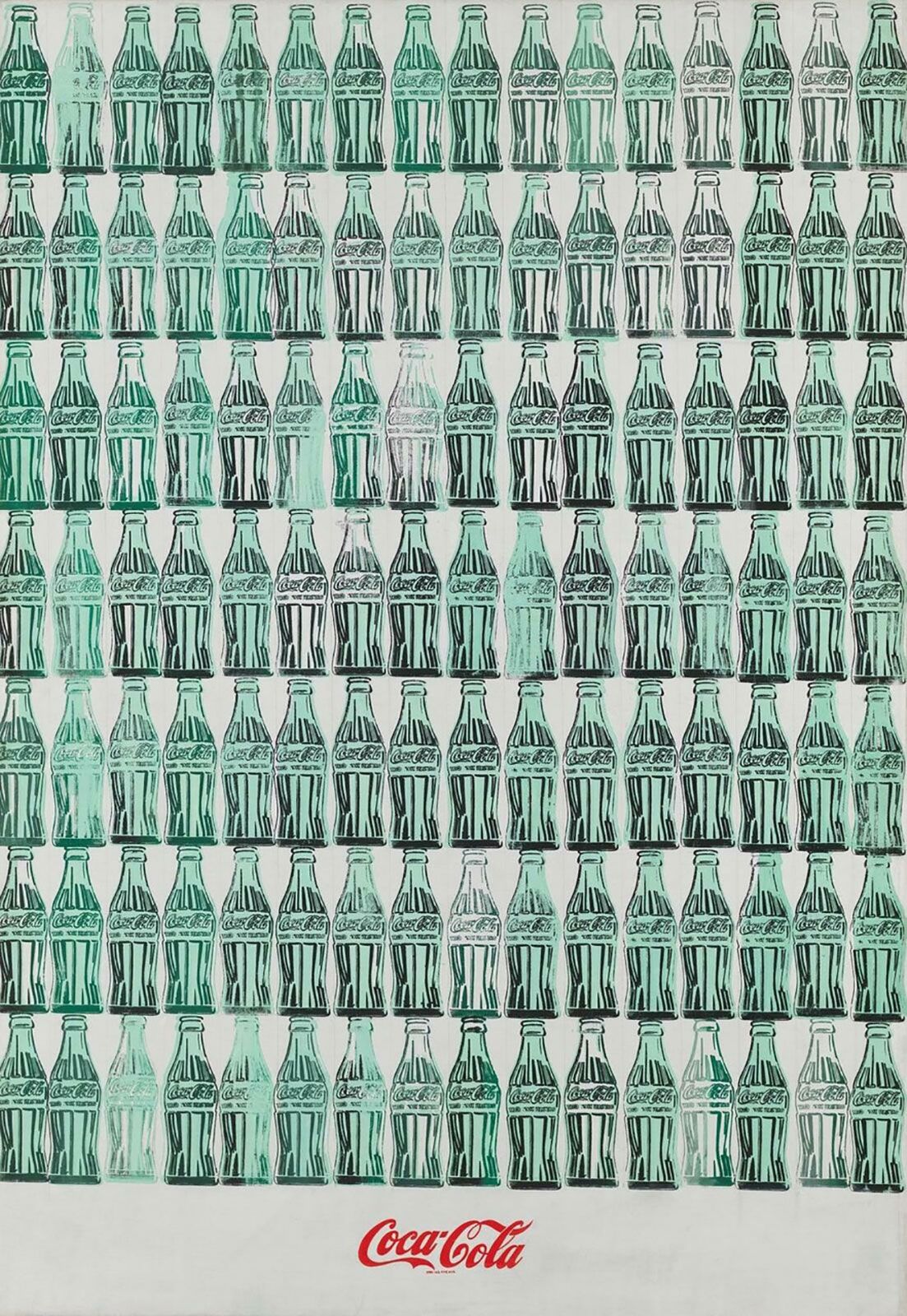

Warhol would refer to his productions of the time as “Business Art”, entering an era in which the artist became consumed with the idea of mirroring corporate practices within the visual arts. This transition might be considered natural taking into account his education and background in advertising; however, at the time, this brazen Warholian conception of commercialisation and monetisation of art practices was met with criticism. In Victor Bockris’ “The Life of Death of Andy Warhol” a drunken encounter with Willem De Koonig at a party in 1962 is described in which the abstract expressionist reportedly told his Pop Art nemesis: “You’re a killer of art, you’re a killer of beauty, and you’re even a killer of laughter“. Embracing capitalism, Warhol’s body of “Business Art” harshly confronted American commodity culture and shaped the art market as we know it today. In essence, pop art was promoted and publicised just like any other consumer product at the time. Appropriating the same strategies as seen in consumer culture, Pop artists also directly depicted consumer imagery, establishing an artistic production and creativity as a commodity that directly referenced consumer products and culture. Warhol’s “Green Coca-Cola Bottles” (1962), one of the earlier silkscreen paintings, displays multiple single images of Coca-Cola bottles aligned in seven regular rows arranging sixteen bottles across the canvas. Its repetitive pattern and standardised format are highly evocative of industrial processes. The brand Coca-Cola, known to everyone inside and outside the elitist art world, made it possible for the broader public to relate to an artwork. Its recognisability was affirmed through the utilisation of commonly known symbols, democratising art for the very first time.

Moreover, as seen in Rotella’s photo emulsions which subjects often depicted pivotal moments in the history of the time, such as the first astronaut’s walk in space as seen in “L’astronaute” (1966), Pop art served as a vehicle to comment on politics. “What was important, I believe, was to get away from abstract art, which was very present in galleries, and do something that was corresponding to the time in which we were living” (Joan Rabascall). While its subjects were not always necessarily direct depictions of political imagery, pop artists mirrored and critiqued a newly present culture of mass media that utilised imagery and language as a manipulative and capitalistic instrument.

Andy Warhol, Green Coca-Cola Bottles, 1962.

In stark contrast to the abstract expressionism at the time, pop artists such as Robert Rauschenberg or Jasper Johns viewed these abstract works as critical, removed from reality and elitist. Ironically, the origins of Warhol’s soup cans have been related to an artistic metaphor utilised by De Kooning himself. In 1960, the abstract expressionist artist had been featured in a movie in which he is interviewed by Michael Sonnenabend and asked: “I want to ask you a question, if you are creating yourself as you painted your picture?” De Kooning responds:

“Everything is already in art. Like a big bowl of soup. Everything is in there already, and you stick your hand in and you find something for you”.