Pop Art in transfer: the Biennale that wasn’t

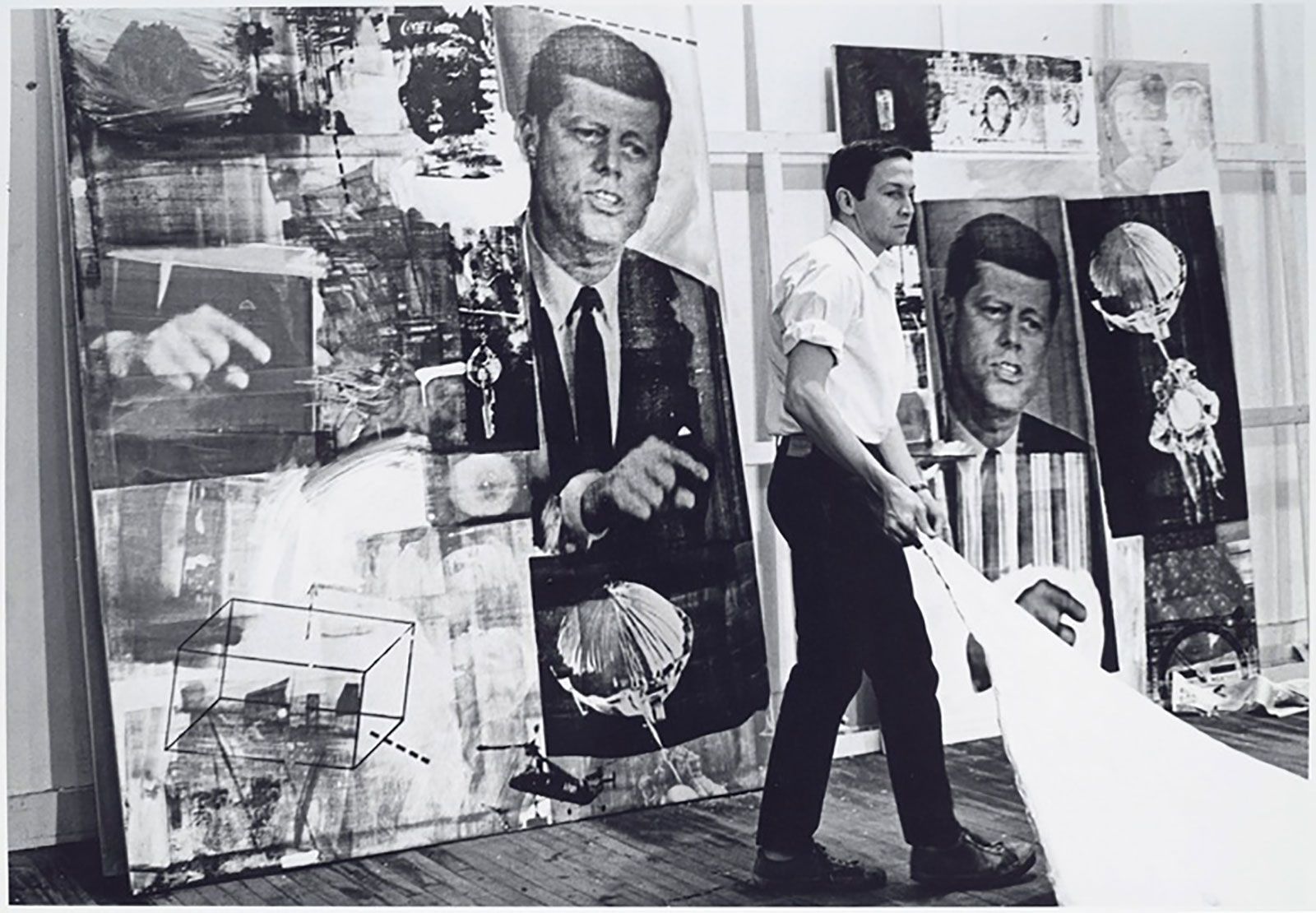

Robert Rauschenberg in preparation for the 32nd Venice Biennale, 1964

When Robert Rauschenberg won the Golden Lion for his silkscreen paintings at the 32nd Venice Biennale in 1964, the art world witnessed the beginning of a pivotal shift within European and American Pop-Art. Whereas the American artists gained recognition and validation amongst the European avant-garde, countries such as France and Italy viewed Rauschenberg’s win as an emblem for American expansionism, the “last frontier” of cultural dominance. Amongst pop artists such as Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol and Mario Schifano, the décollage artist Mimmo Rotella was meant to present a pioneering selection of new works that would have placed him amongst his American counterparts. Read more in Cardi Gallery’s Online Magazine this week about how a biographical moment of arguably small significance in Rotella’s life impacted the course of European Pop Art and the legacy of the artist until today.

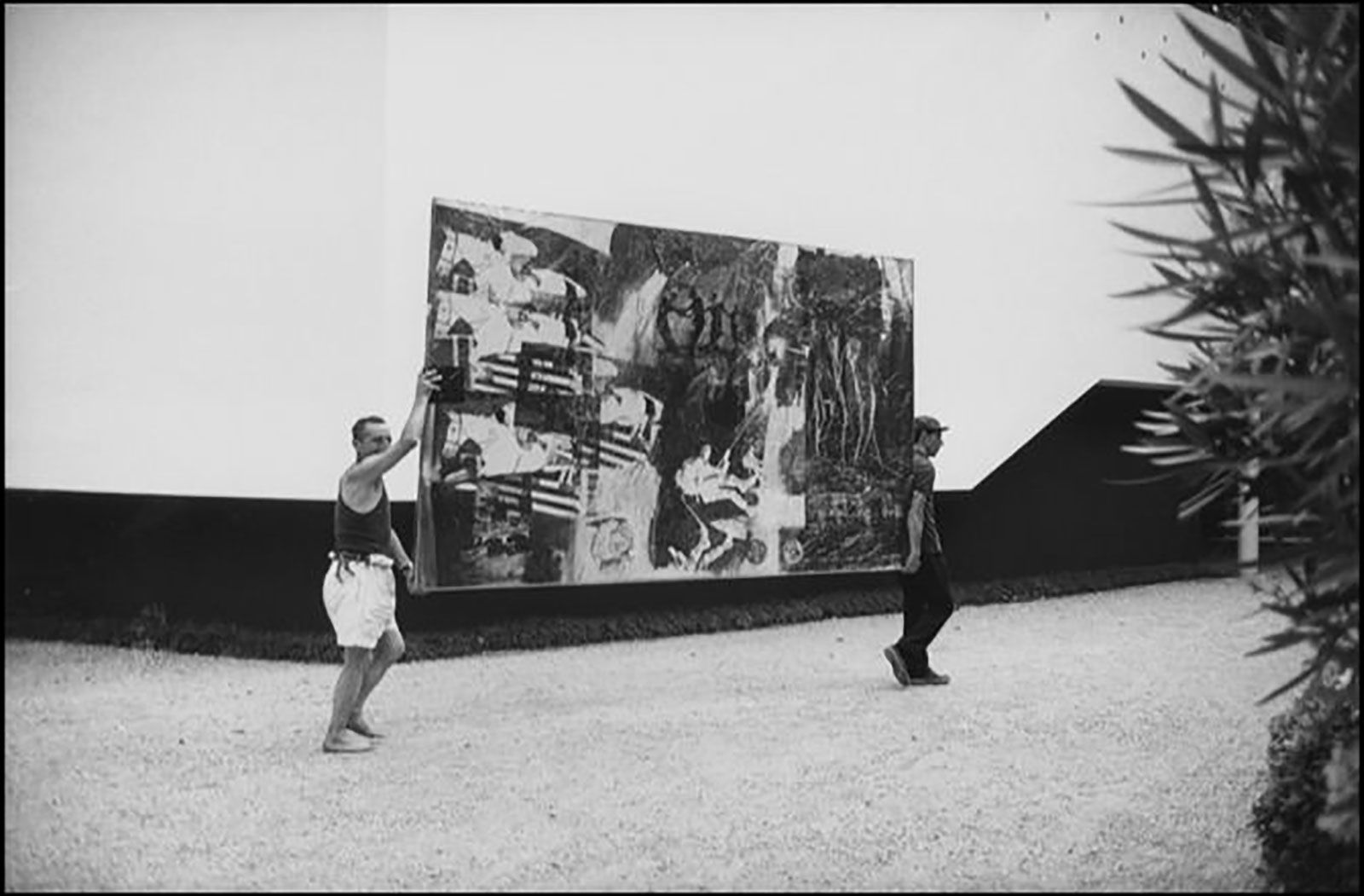

Installation of Robert Rauschenberg’s, Express, at the 1964 Venice Biennale. Photo by Ugo Mulas

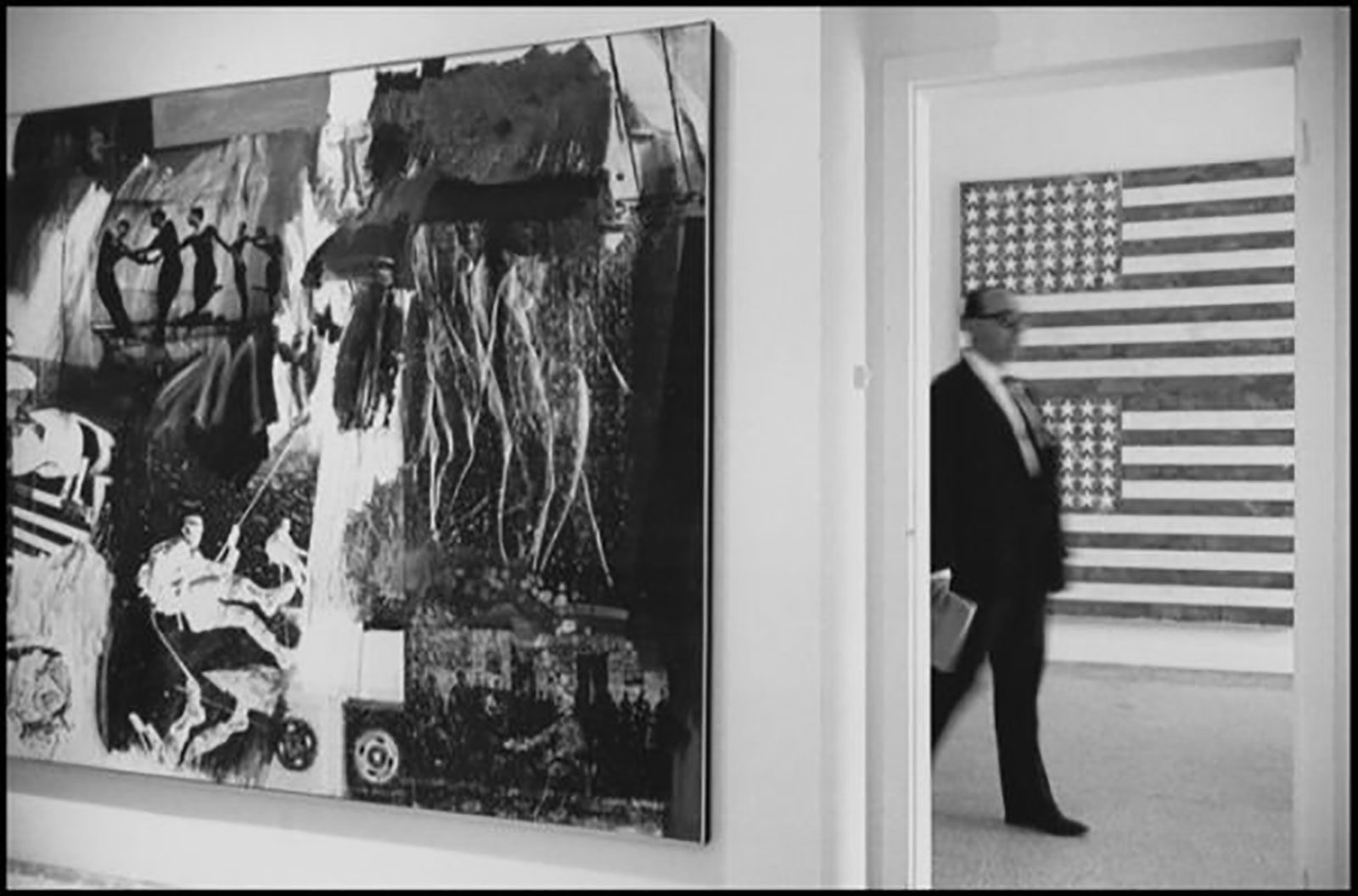

Robert Rauschenberg installed at the 32nd Venice Biennale, 1964 in the background Jasper John’s Double Flag, 1962

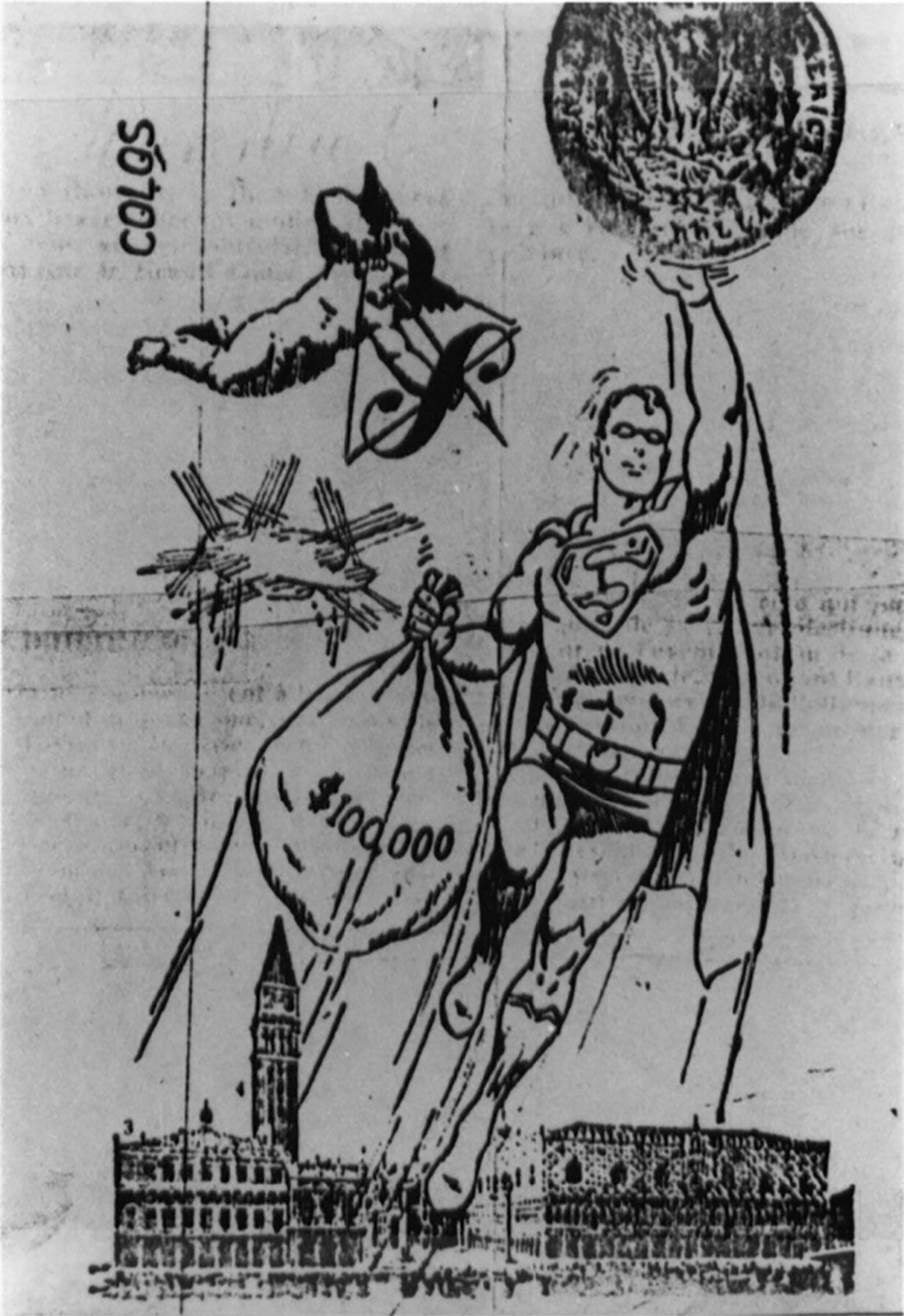

Rauschenberg’s win of the prestigious Golden Lion award became controversial for various reasons. For one, the artist initially decided to showcase only one painting at the U.S. Pavilion in the Garden for which he would have had to be ineligible to receive the grand-prize. At the time, the rest of his paintings were displayed at the American consulate and due to a last-minute consultation with the commissioner of the U.S. Pavilion Alan Solomon they were quickly moved to the Biennial’s main exhibitor space. While this last-minute effort to manipulate the country’s representation in the context of the prize’s eligibility requirements was met with harsh criticism, it was furthermore the cultural implications of Rauschenberg’s win that prompted an uproar of concern within Italy’s arts community. Amongst the European avant-garde at the time, the American efforts to promote Pop-Art were seen as an attempt to expand American pop-culture on a global scale. The era of the Kennedy administration heralded a time of economic and cultural optimism that embraced the culture and the arts as a harbinger of progression. Promises of liberalism following years of Eisenhower’s conservatism saturated the landscape of American culture, directly influencing the activities following art movements such as that of the abstract expressionists. Within this context, Rauschenberg emerged on the international art scene as a form of cultural envoy, emblematic of the importance that the progression towards an avant- garde represented for the cultural efforts of the American administration at the time. Enlisted to mark a prosperous societal departure from the post-war era the avant-garde was an essential emblem of new American values. Before 1964, the French had traditionally dominated the awards of the coveted Golden Lion Award. Outraged reactions across Europe started to proclaim the end of the European School. In France, the headline of Arts magazine read: “In Venice, America Proclaims the End of the School of Paris and Launches Pop Art to Colonize Europe”. The newspaper “Observateur” published a satirical drawing of Rauschenberg displaying him as the American Superman character flying of the Doge’s Palace holding up the prized golden coin and a sack with price money.

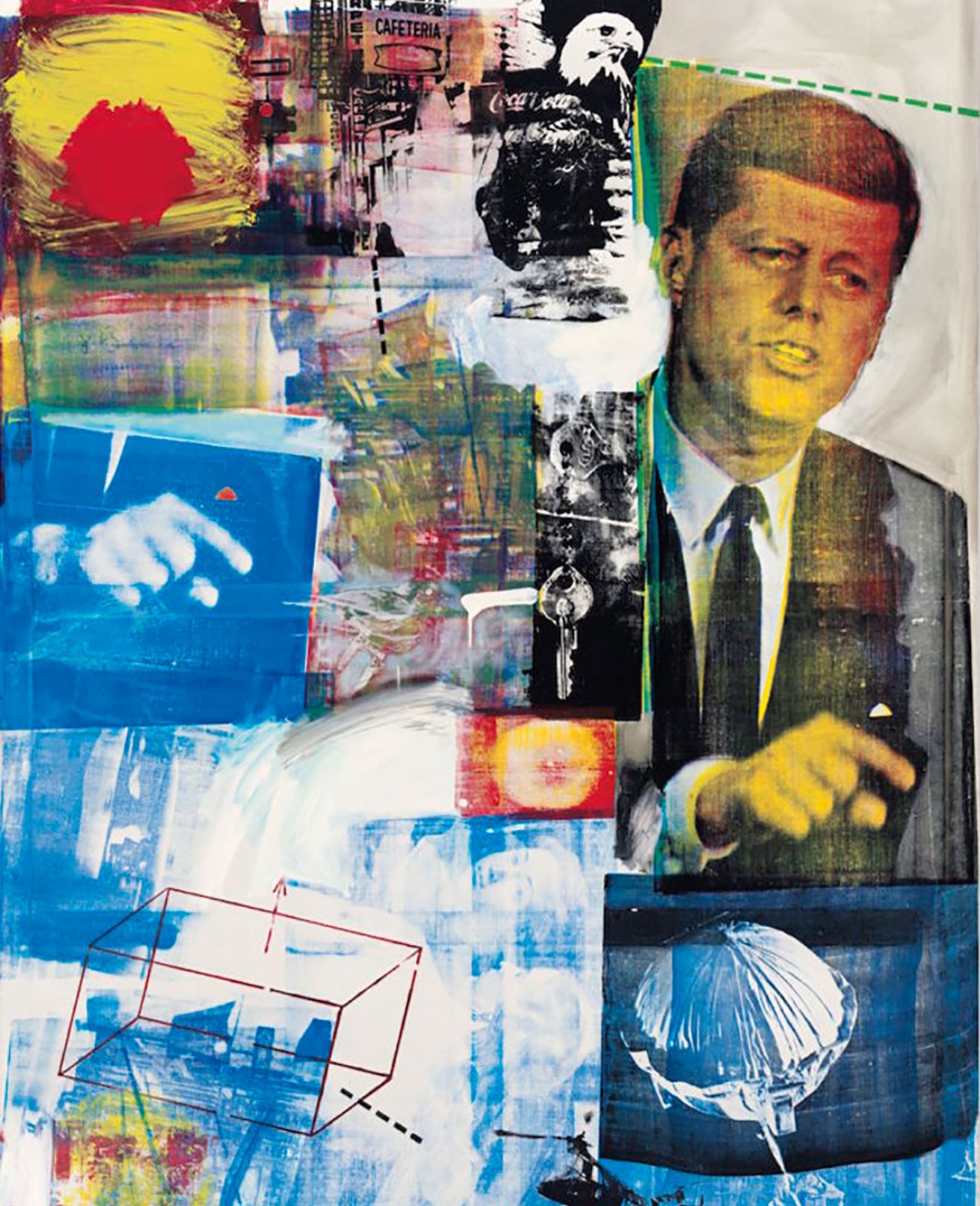

The 32nd Venice Biennale marks a moment in time where Rauschenberg’s win manifested a broader acceptance that in the words of Alan Solomon: “The whole world recognizes that the work art centre has moved from Paris to New York”. Europe’s critical voices reacted to this statement in turn: “The whole world? Our entire little world is excited by this declaration of war. All we talked about was the Americans’ demands”. Rauschenberg’s participation and win of the Golden Lion ultimately introduced the U.S. as a new cultural leader. The artist’s specific language of pop-art imagery was directly informed by American culture at the time, acting as a vehicle for the Americanised icons of power and influence. Specifically, the French art critics at the time were dismayed by the charged military imagery and symbolism Rauschenberg appropriated. Its important here to consider that at the Biennale, every artistic work became politicised. Within the context of increasing American global consumerism sweeping through post-war Europe, it seemed as though even the high culture was not able to succumb to capitalistic influences. Rauschenberg’s silkscreen paintings indeed represented a new age of American Pop-Art saturated by the imagery of war, politics and consumer culture through American products such as Coca Cola etc. While the triumph of Pop-Art in both Europe and the U.S. promoted the aestheticisation and further monetisation of consumer culture, Rauschenberg specifically symbolised a celebration of American society and belief in American liberalism. Moreover, this moment marked a departure of an antiquated notion of modernism that was still being upheld by french art critics specifically and was later also embraced by American art critics such as Clement Greenberg who found himself not far from the European opposition, clinging onto traditional formalism.

Editorial Cartoon, Des dollars chez les Doges, France Observateur, June 25, 1964

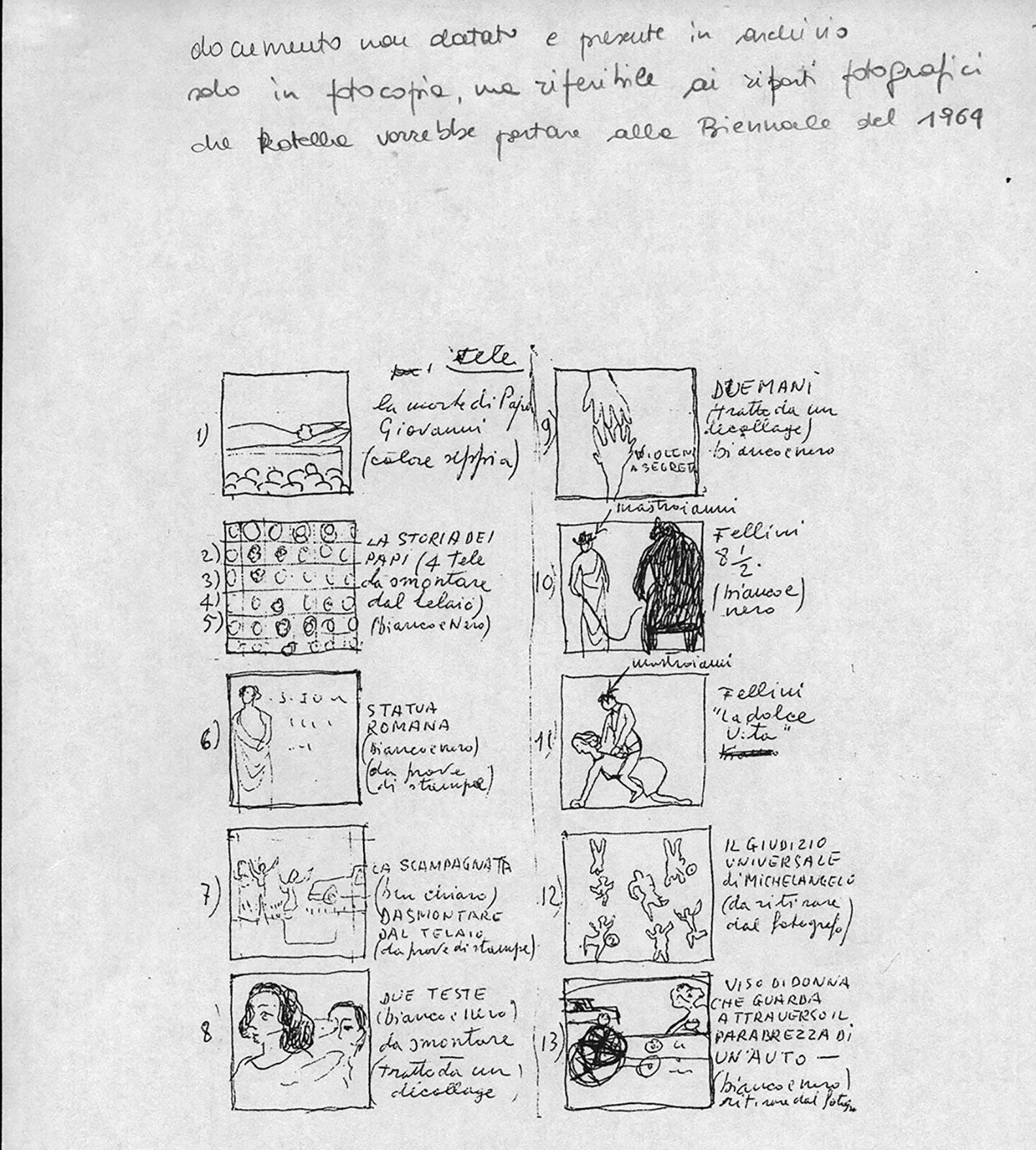

Drawing for the proposed installation at the 32nd Venice Biennale

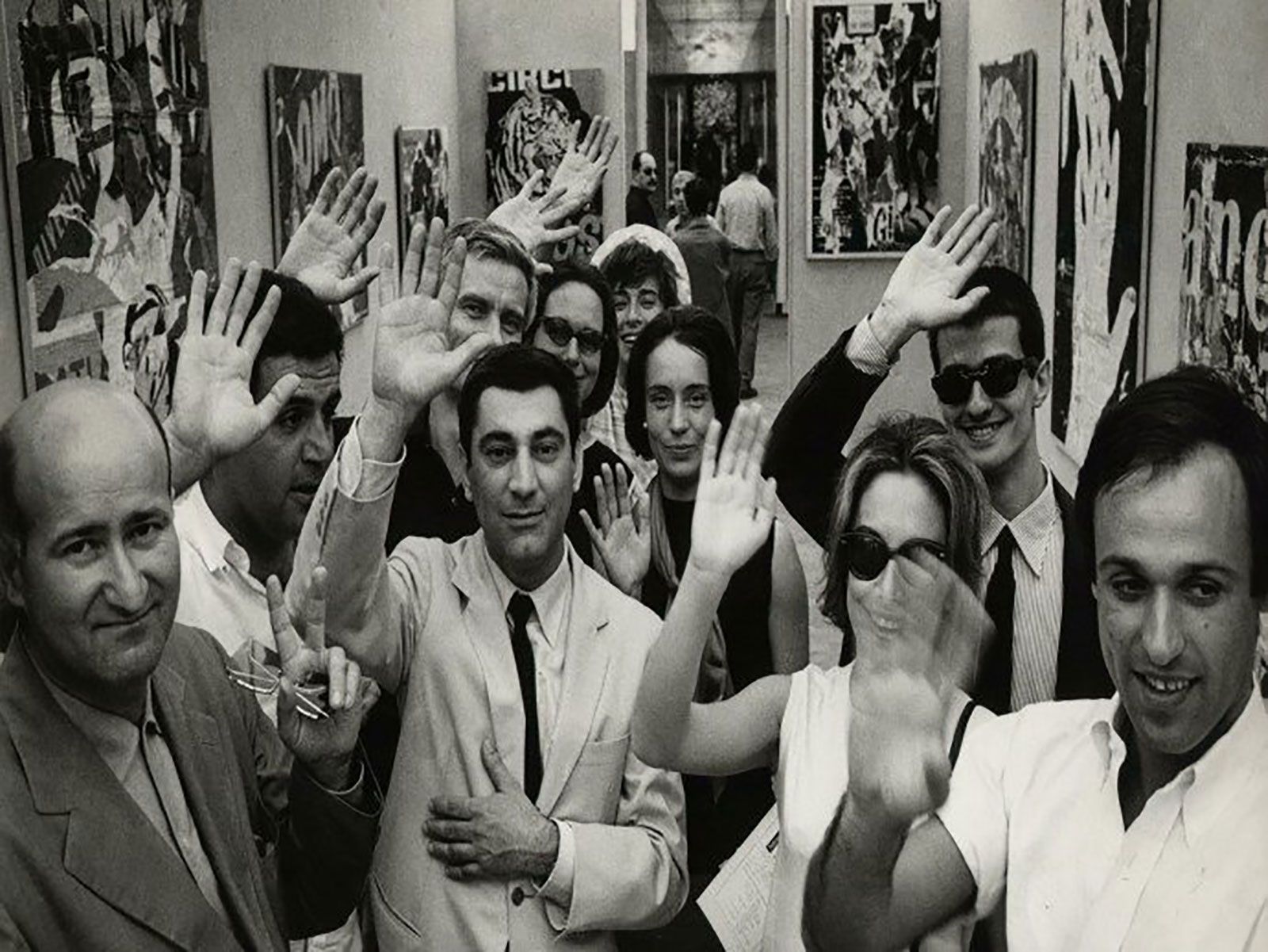

Rotella’s friends at Rotella’s Biennale exhibition including Mario Schifano (on the right), waving to him through the camera

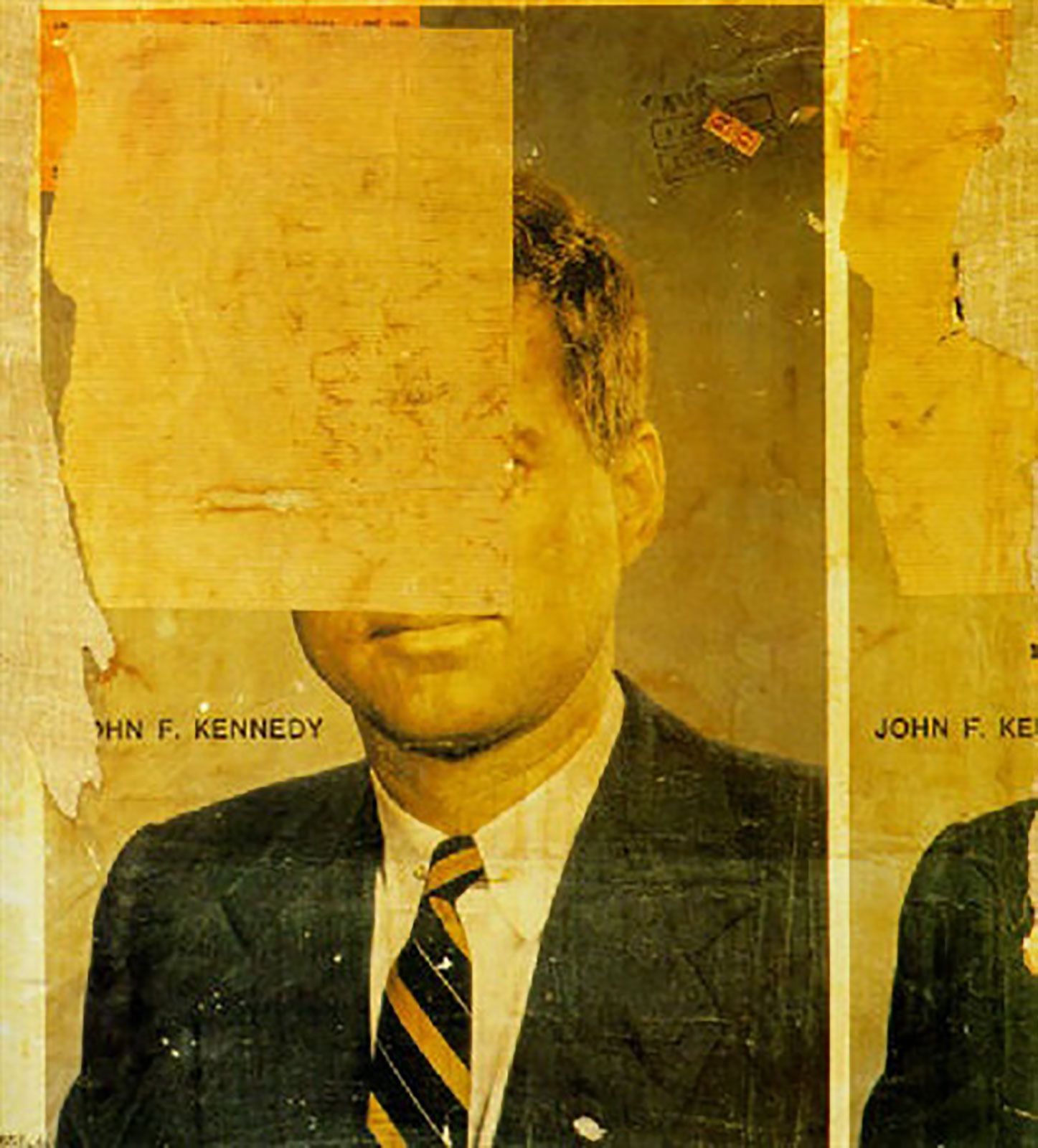

Mimmo Rotella, John F. Kennedy, 1963

Robert Rauschenberg, Buffalo II, 1963

Amongst the European Pop-Artists, Mimmo Rotella was a key figure who through his décollages, torn advertisement and film posters, introduced the imagery of iconography of film stars as early as 1961. In anticipation of the Venice Biennale, Rotella prepared a new body of work triggered by yet another artistic crisis and an urge to reinvent his practice. At the height of his artistic career and critically acclaimed exhibition history, Rotella devoted himself to the exploration of a mechanical and photographic technique, the photo emulsion. In contrast to the productions of Warhol and Rauschenberg, he sought to refrain from gestural representation. While Warhol’s silkscreens according to Germano Celant represented “a sign of the exhaustion of the artist’s gesture”, Rotella aimed to utilise the photographic emulsion as a tool of direct transfer, visualising the reality depicted through the mass media of the time as closely as possible.

In February 1964 Rotella was charged for the illegal possession and trafficking of drugs, as well as the possession of pornographic material. Ultimately released from prison after five to six months due to insufficient evidence, the sentencing provoked in Rotella an intense frustration with the Italian law and its artistic community. Part of the betrayal the artist recounted to have felt was directly in connection with the preparation of that year’s edition of Venice Biennale which prior to his imprisonment Rotella had prepared in collaboration with his art dealer and gallerist Plinio De Martiis. The preliminary selection of works was meant to introduce the public to Rotella’s pioneering photo emulsions for the very first time, taking advantage of the global stage and critical limelight provided by the honour to participate at the Venice Biennale.

Rotella entrusted his friend De Martiis to continue to develop the imagined installation for his dedicated room at the Biennale while he began his prison sentence at the Regina Coeli prison. In the following months however, the letter correspondence between the artist and his affiliates on the outside revealed an increasing concern, even disinterest Rotella’s new body of work. Beginning of April that year the critic and Rotella’s close friend Pierre Restany wrote to him: “Plinio is not happy with them, given their resemblance to Warhol’s pictures. I believe for my part that your spirit is completely different.”. Similar doubts were expressed by Giorgio Franchetti who was one of Rotella’s most important collectors at the time and wrote to him directly: “(…) there has just been an exhibition of Warhol’s, focused entirely on photographic transfers. This would certainly give rise to misunderstandings“. While we can not identify for certain wether it was the concern to appear too identical to the American artist or the commercial fear of presenting a new body of work that until that date had remained unexposed to the market, the archived letters reveal an unfortunate development outside of Rotella’s ability to intervene.

Mimmo Rotella, Jacqueline Kennedy, 1963

Andy Warhol, Nine Jackies, 1964

“I just take images and photograph them. The only thing I’m interested in is this pure act of approbating the image and reproducing it on the canvas”

(Mimmo Rotella)

The decision was thus made by De Martiis to showcase a selection of décollage works which Rotella had made the years before his sentencing. Unable to attend his display at the Biennale, his friends and peers including artist Mario Schifano sent him a photograph from his exhibition waving to him through the camera. Once released from prison in the summer of the same year Rotella visited the exhibition before its closing date with friend and artist Lucio Fontana. As a consequence of the events of this year Rotella decided to transfer permanently to Paris where in collaboration with Restany, he eventually showcased the photo emulsion a year later during an exhibition at “Galerie J” in Paris in 1965 for the occasion of a small scale exhibition titled “Vatican IV”.

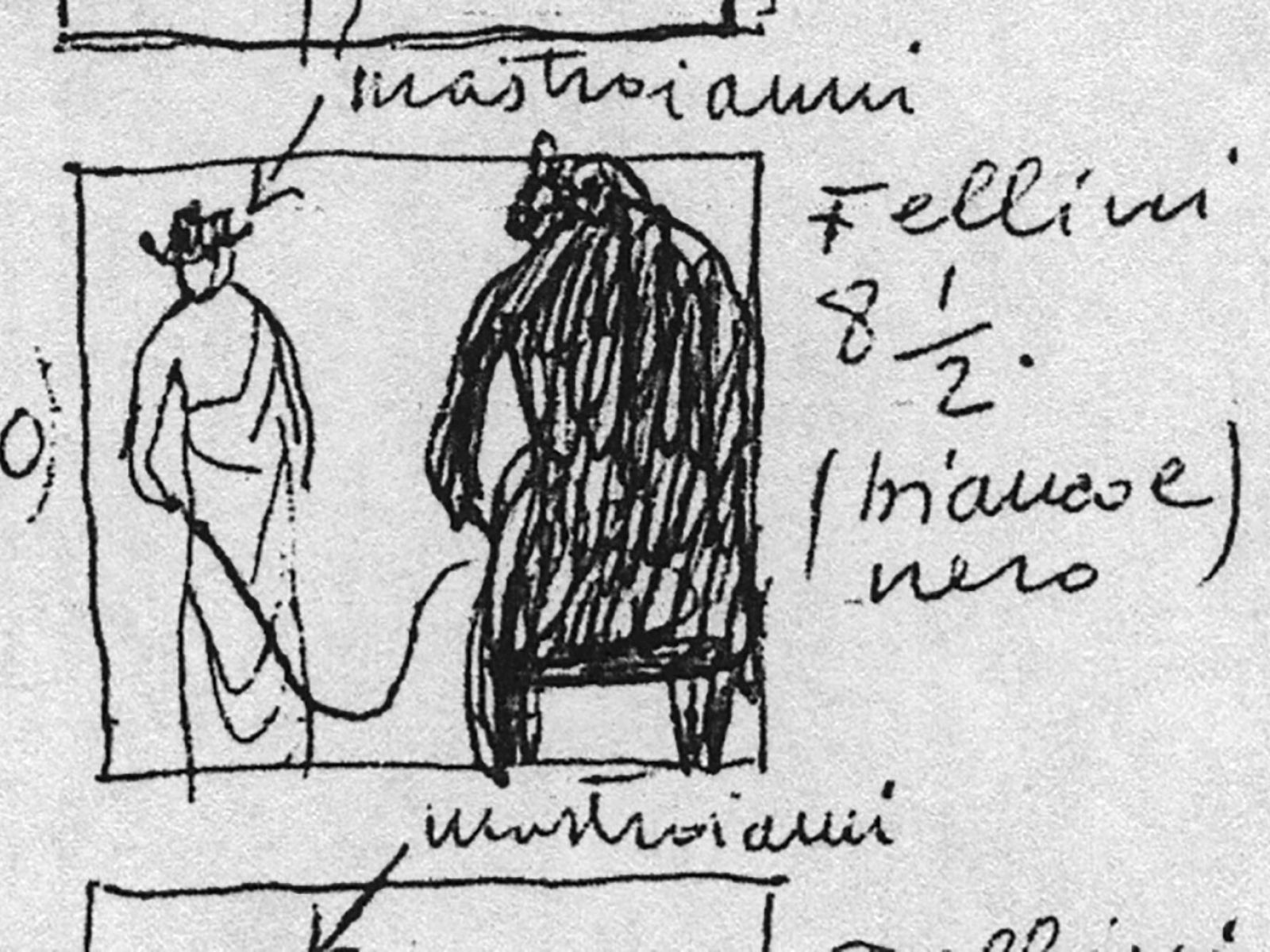

At TEFAF New York Online Viewing Room this year, Cardi Gallery is proud to present one of the works featured within the original list of works to be presented at the 32nd Venice Biennale: “8 1/2” (1963). The work belongs to a series of photo emulsions dedicated to the film productions of famous Italian director Federico Fellini. Coloured in a blue monochrome tone the work displays a still from a scene of the film “8 1⁄2” that since its debut in 1963 has been recognised as Fellini’s most acclaimed production. The composition of the figures suggests the image source stems from advertisement material. Additionally, the number eight, paired with the illustration of a scissor, is visible on the work’s right-hand side. Rotella appropriated the image from a pivotal moment of Fellini’s film, referred to as the “Harem” scene, visualising the protagonist Guido Anselmi’s internal conflict further contributing to his deteriorating state of mind. Anselmi, portrayed by actor Marcello Mastroianni, dreams about a confrontation with all the woman that throughout his life, have embodied different personal fulfillments of his imagination.

We may be left to wonder how a presentation of a new body of work at the Venice Biennale might have influenced the artist’s legacy. Curator of the exhibition “Mimmo Rotella. Beyond Décollage: Photo Emulsions and Artypos. 1963-1980” Antonella Soldaini wrote in her exhibition essay: “The failure to show the photo transfers in his room in Venice was to leave its mark on the history and fortune of this kind of work; in fact they would not burst onto the public scene and be represented, as the artist would have wishes, at an event with international clout like the Venice Biennale, but would be shown at less significant occasions […] in reality Rotella, by moving to Paris, would distance himself from the nerve centre of the international art scene which, following the award of the Grand Prize at the Venice Biennale to Robert Rauschenberg and the substantial presence of American Pop Art at the event, had inexorably shifted to New York. With the consequences that his new production of reportages would remain limited to European circles and only later be presented to the scrutiny of the critics and public on the other side of the ocean.”

Cardi Gallery invites you to read Antonella Soldaini’s full essay of the importance of Rotella’s photo emulsions “The Photo Emulsion and the myth of the artwork’s objectivity” in our new exhibition catalogue for the major Mimmo Rotella retrospective on view at Cardi Gallery London until the 12 of December 2020.

Mimmo Rotella’s 8 1/2, 1963 in the original sketch for the 32nd Biennale

Mimmo Rotella, 8 1/2, 1963