Painting in action: Shozo Shimamoto

Shozo Shimamoto making a painting by hurling glass bottles of paint against a canvas at the “2nd Gutai Art Exhibition”, Ohara Kaikan, Tokyo, c. October 11–17, 1956. Courtesy Shozo Shimamoto and the former members of the Gutai Art Association, and of Museum of Osaka University.

“Create what has never been done before!”. Encouraged by the words of Jirō Yoshihara, artists at the first Gutai Art Exhibition came together to create a revolutionary body of work which epitomised the complex discourse of originality and authenticity of both the pre- and post-war period in Japan. On view at Cardi Gallery Milan, an outstanding selection of works by artist Shozo Shimamoto, co-founder of the movement, presents the dynamic spirit of Gutai. Through performative and dynamic performative elements the artist became a significant point of reference for post-war expressionist action painting, inspired by and in creative symbiosis with American artists of the time such as Jackson Pollock.

“Even if my method seems shocking and violent – crushing bottles and shooting cannons at the canvas – because I am an artist my purpose is to make the work beautiful, to show the beauty of everything. I’m just working on creating beauty.”

(Shozo Shimamoto)

Widely regarded as one of the most influential Japanese artists, Shozo Shimamoto was the co- founder and original member of the post-war art movement, The Gutai Art Association. Through various artistic practices, the members of Gutai sought to explore the abstract, establishing the creation of art and beauty within a moment of destruction, decay and damage. Enclosing two meanings the term translates to the “concrete” and “embodiment”, inviting the artists to physically engage with the artwork, object, the concrete form. The ethos of the movement largely followed the belief that an artwork is the physical result and representation of the gestural artistic transfer to the work’s surface. Working with approximately 59 avant- garde Japanese artists, the group, founded by Shimamoto and Yoshihara, was active from 1954 to 1971 and produced a complex yet historically important body of work that sought to reflect on the experienced violence of the war. Emerging from the Kansai region, known for its traditionalism the group aimed to fully transform Japanese Art, introducing innovative artistic techniques. The re-incarnation of art and culture in post-war Japan followed a deadly and violent period, seeing the Hiroshima bombing and the events of the Second World War. Part of this rebirth was a return to the question of material and the desire to break boundaries and seek innovation. Working with a variety of media, from technology, installation, performance to gestural abstraction. Establishing art within a multi-genre context, Shimamoto and the other members rejected formal terms such as painter and embraced the artist as an emblematic term to describe the encompassing act of making an artwork for which the act of making was part of the result.

“Let’s bid farewell to the hoaxes piled up on the altars and in the palaces, the drawing rooms and the antique shops. They are monsters made of the matter called paint, of cloth, metals, earth, and marble, which through a meaningless act of signification by humans, through the magic of material, were made to fraudulently assume appearances other than their own. These types of matter [busshitsu], all slaughtered under the pretense of production by the mind, can now say nothing. Lock up these corpses in the graveyard. Gutai Art does not alter matter. Gutai Art imparts life to matter. Gutai Art does not distort matter.”

(Gutai Art Manifesto, Jirō Yoshihara 1956)

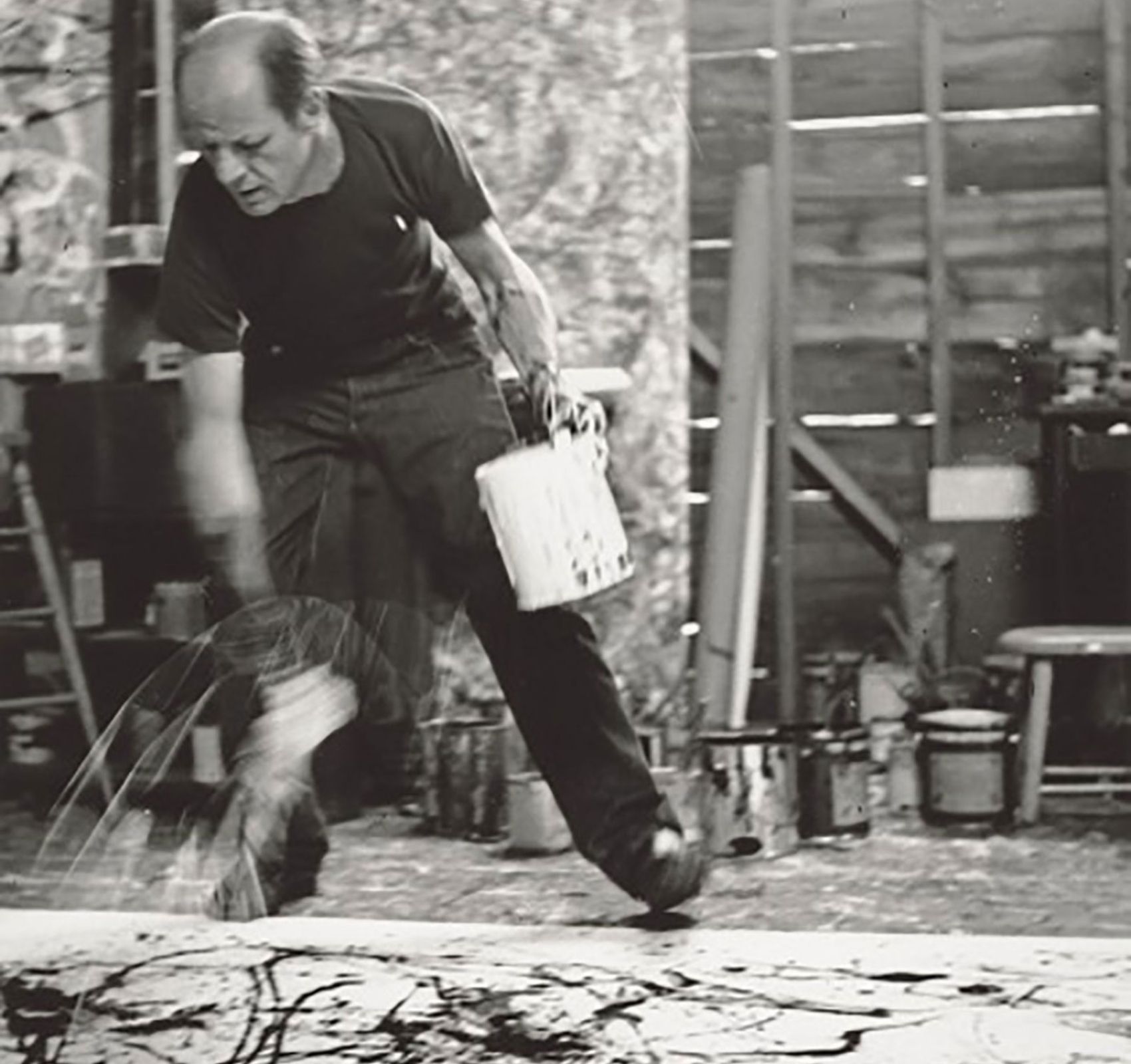

Jackson Pollock working in his studio

Detail of Jackson Pollock, Red Composition, 1946

Credited with the invention of the movement’s name Shimamoto gained international recognition with his essential contribution to the legacy of Gutai. The artist’s dynamic, visually abstract practice was widely informed by the group’s aim to merge material properties with human qualities. Appropriating developing art theory of the 1960s concerning Abstract Expressionism as well as Ephemeral Art, Shimamoto’s practice often involved the smashing and throwing of vases and bottles filled with paint or the slashing of the canvas, also referred to as action painting. Similar to other avant-garde movements of the post-war era, the rejection of the painting and representational forms within art was a significant leitmotif for the Gutai group. Shimamoto’s destructive intervention to the canvas perfectly embodied the spirit of the movement which favoured concept over form, seeking to expand the notion of art beyond the boundaries of the traditional painting. His practice was furthermore fundamentally shaped by action painting. This term is attributed to a selection of painters from the post-war era whose technical approach emphasised elements of gestural physicality that became an essential element of the result of the artwork. One of the most famous artists of this category is undoubtedly the American Jackson Pollock who his globally acclaimed for his famous large-scale drip paintings. Artists such as Pollock, Yves Klein or Georges Mathieu were greatly influenced by the activities of the Gutai movement which anticipated various artistic practices such as Body Art, Happenings and other performative painterly gestures such as elements found within action painting.

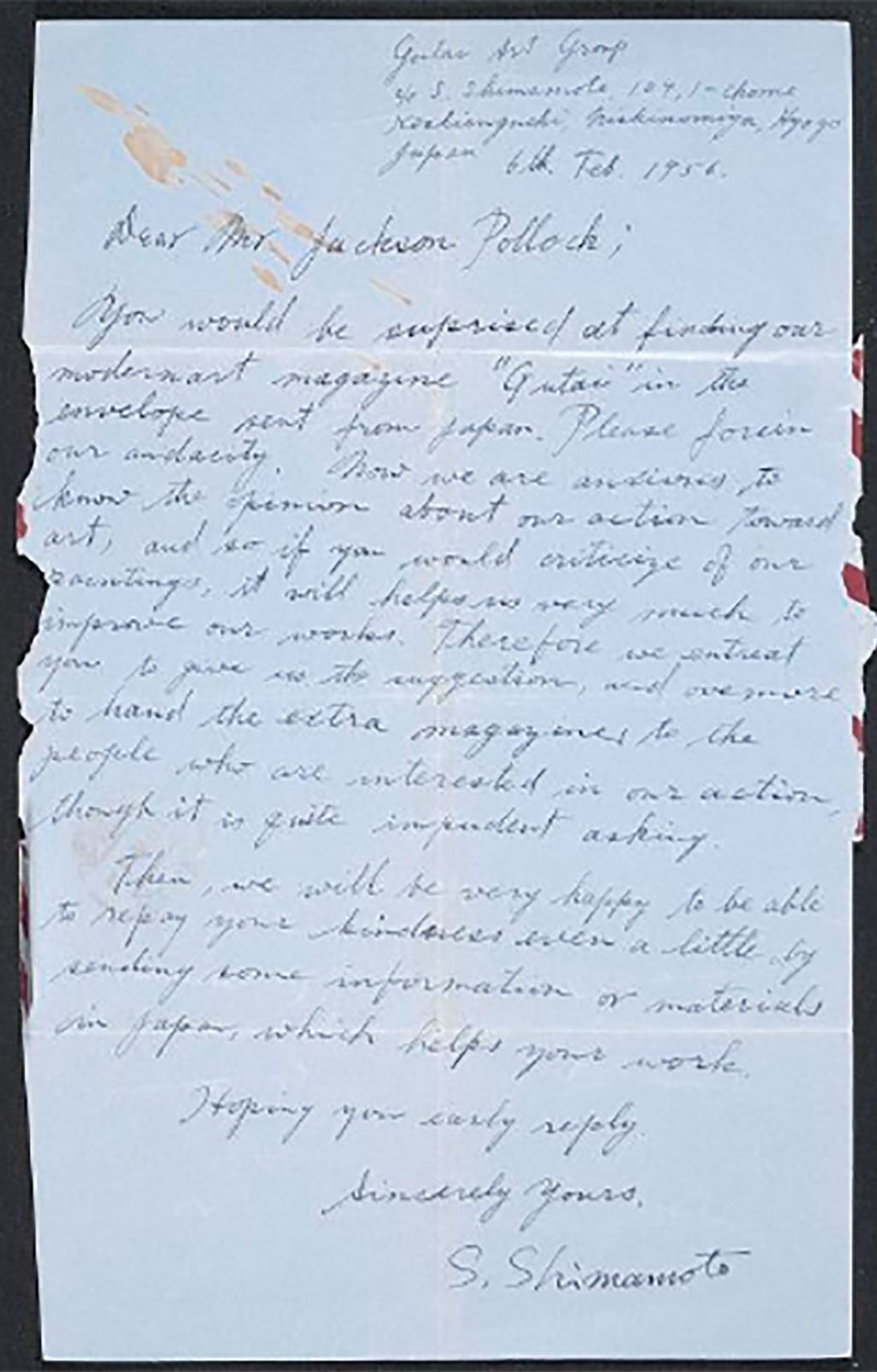

On behalf of the Gutai group, Shimamoto wrote to Pollock in 1956 informing the American artists about the existence of the group and its motivations. Enclosed he sent copies of magazines and the Gutai journals that were later found in Pollock’s possession following his death. The journals play a key role in the establishment of the group globally. The document, the first Gutai Journal from 1955, was an important tool of communication for the group and the very first collaborative project that the artist evolved before the organisation on an exhibition.

Dear Mr. Jackson Pollock,

You would be su[r]prised at finding our modern art magazine “Gutai” in the envelope sent from Ja – pan. Please [forgive] our audacity. Now we are anxious to know the opinion about our action toward art, and so if you would criticize of our paintings, it will helps us very much to improve our works. Therefore we entreat you to give suggestions and overmore to hand the extra magazines to the people who are interested in our action, though it is quite impudent asking. Then we will be very happy to be able to repay your kindness even a little by sending some information or materials in Japan, which helps your work. Hoping your early reply.

Sincerely yours,

S. Shimamoto

[About Yoshihara] “It is not so much his own art as his independence of mind, his defiance of bureaucracy, his willingness to seize the opportunity of a clean slate afforded by the historical situation of postwar japan, and his encouragements to be as radical as possible that explain the attraction he exerted on artists who were a generation younger. His interest in performance and in the theater-the only domain where he was as innovative as the other members of Gutai-also played a major role in defining the group’s activity. It is this performative angle from which Gutai looked at Pollock that resulted in one of the most interesting, albeit short-lived, “creative misreadings” of twentieth-century art. Because they knew next to nothing about the context that had presided over the invention of Pollock’ s drip technique, because they read it through cultural codes that were utterly foreign to the American artistic ambience, the Gutai artists were able to zero in on aspects of Pollock’s art that would become available to Western artists (notably the post-Minimalist proponents of “antiform”) only fifteen years later.”

Hal Foster here described a survey of Pollock’s art from a purely unique Japanese perspective saturated in the cultural and political landscape of the country. These readings were intensified through an academic exploration that for example, saw Harald Rosenberg’s notion of abstract expressionism as “arena for action” as a crucial manifesto that would inspire and contextualise the works and performances of Shozo Shimamoto greatly. Within the avant-garde formation, Shimamoto was specifically concerned with the rejection of the paintbrush, a tool which had traditionally dominated the painting. Similarly to Pollock, Shimamoto’s methods were closely connected to the body, its movement and gestures. In a written essay titled “Idea of Executing the Paintbrush” Shimamoto writes in 1957 addressing painters and encourages them to embrace paint as the medium, rejecting, “executing” the brush. The artist thus began to employ alternative methods of transferring paint to a canvas or other objects such as through the throwing and smashing of paint-filled bottles or cannons, at times even with by utilising a bicycle, umbrellas or vibrating devices. The action and the performative, “the arena”, was consistently the focus of the work. After its creation, Shimamoto’s canvasses are often titled after the locations in which the public creation of the work tool place.

Today, Shimamoto’s works are largely presented in permanent collections around the world in permanent collections such as at the Tate Collection, London, the National Museum of Modern Art, Rome, the Contemporary Art Museum, Tokyo, the Pompidou Centre, Paris, the Fondazione Morra, Naples, Italy. His work has also been included in significant exhibitions at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles and the Jeu de Paume, Paris. In 1996 Shimamoto was nominated to win the Nobel Peace Prize. In 2013 the artist died in Osaka.

Shozo Shimamoto Bottle Crash performance

Shozo Shimamoto performance