Mono Ha: The School of Things

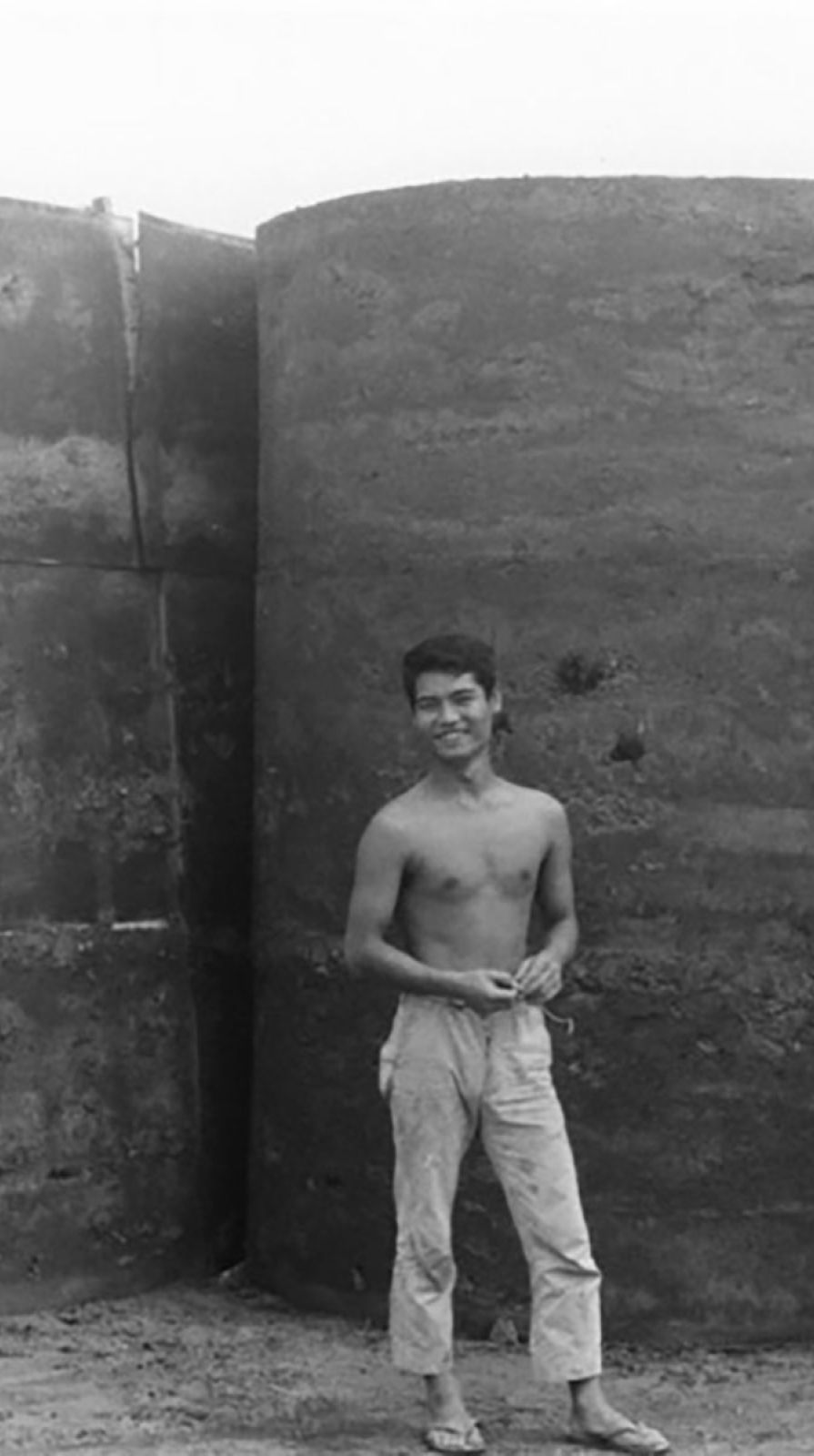

Phase Mother Earth, 1968. Production shot. Susumu Koshimizu (left), Katsurō Yoshida (center), Nobuo Sekine (far right).

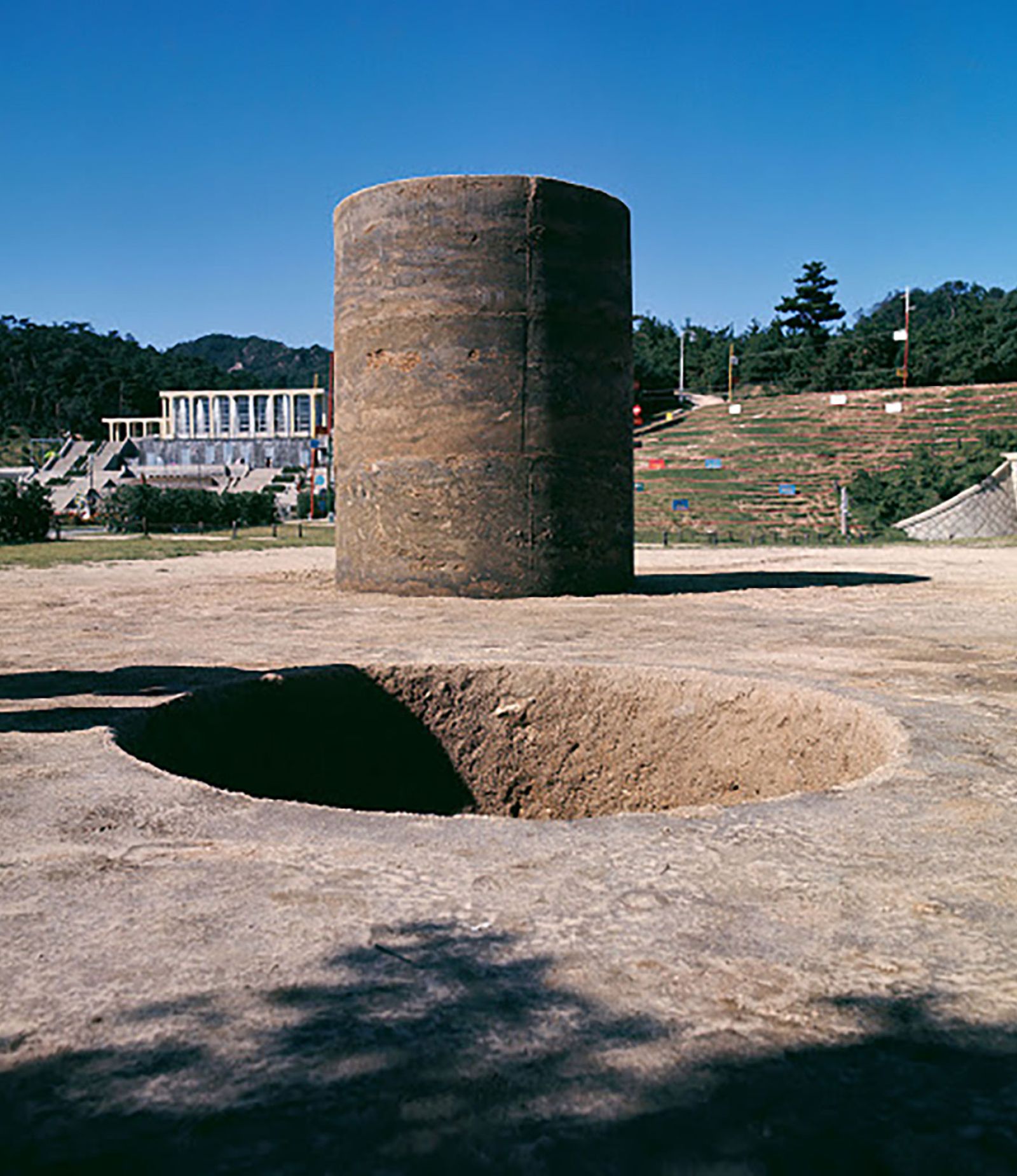

“Faced with this solid block of raw earth, the power of this object of reality rendered everybody speechless, and we stood there, rooted to the spot… I could feel the passing of time’s quiet emptiness… That was the birth of Mono-ha”.

United in their concern for the metaphysical element within the contemporary art practice, the artist of the Mono-Ha art movement radicalised the Japanese post-war art practice. Translated to “The School of Things”, the term loosely refers to a group of artists with no direct associations with each other but their strive to create anti-modernist and conformist. Similar to the structure of the Arte Povera movement, these artists also shared affinities towards the utilisation of everyday material and nature. Initially formed by the artists Lee Ufan and Nobuo Sekine, the movement would later also include Japanese artists such as Kishio Suga, Susumu Koshimizu, Kōji Enokura, Jiro Takamatsu, Noriyuki Haraguchi and Noboru Takayama.

Nobuo Sekine, Phase of Nothingness, 1969. Installed at the Japanese Pavilion, 35th Venice Biennale, 1970.

The artists of the Mono Ha group developed a critical confrontation with many concurrent Western art movements of the time. Within the artist’s experimentation with installation art and earth art, the Mono-Ha group made use of elements and references while upholding a strong critique and rebellion against the traditional values of Western Modernism.

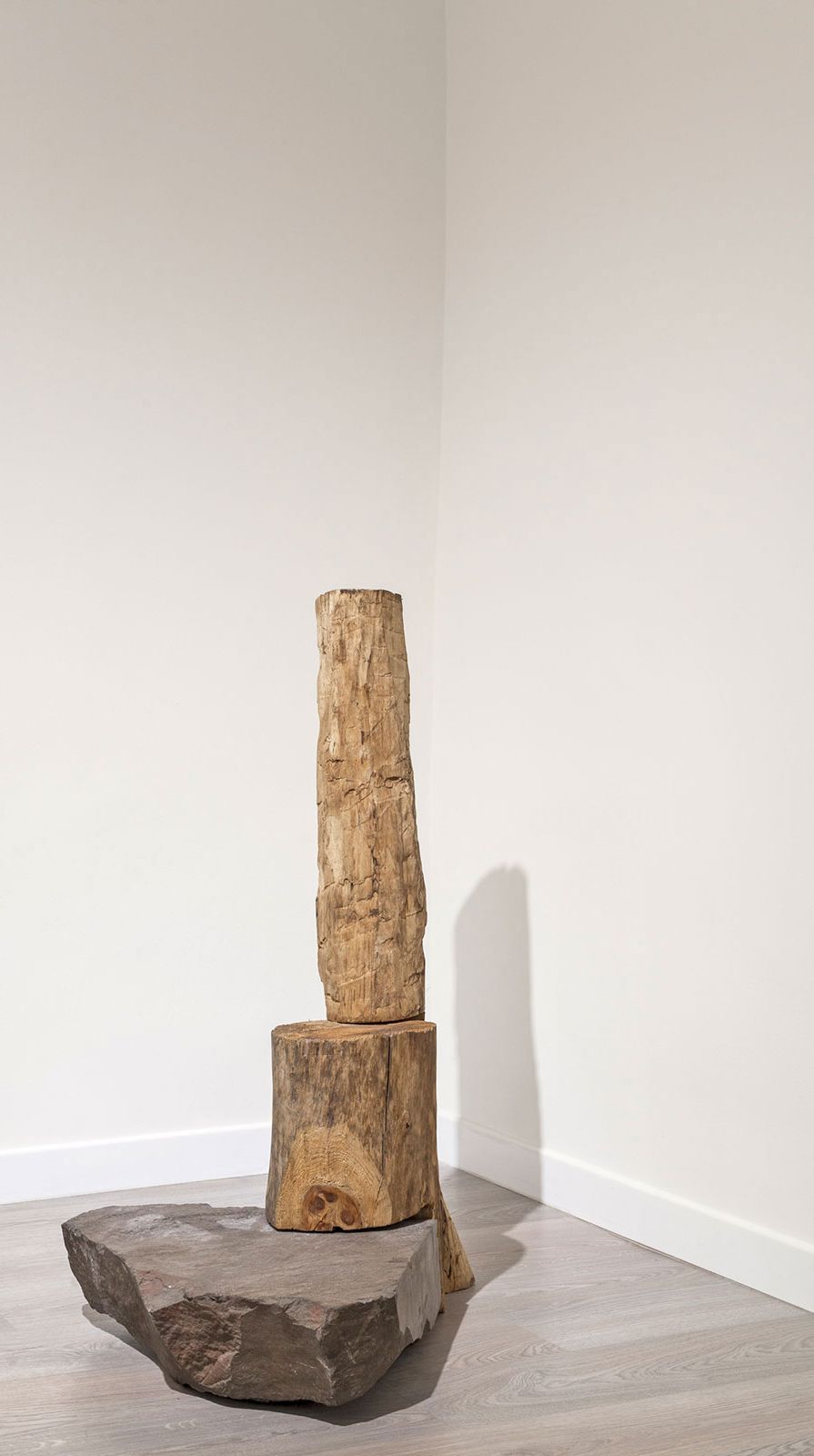

Lee Ufan, Relatum, 1968.

The core belief and action of the Mono-Ha were to remove the central role of the artist as someone who is more than just a creator of things, but moreover “a re-arranger of things into artworks”. Challenging the role of the artist and the meaning of art itself, these artists drew attention to the symbiotic relationship between the artwork, as the thing, and its environmental space that surrounds its exhibition. Although the movement responded in rebellion to Western art movements, its similarities to Minimalism and, moreover, the Italian Art Povera are undeniable. Artists of the Mono-Ha worked with both natural and industrial materials such as paper, wood, stone, soil or steel. Their arrangement of “things” (mono) reconfigured these various elements in an often minimalistic way, reducing the object to its primary form.

Founded by Lee Ufan and Nobuo Sekine, the movement emerged during political and cultural tensions of the 1960s. A majority of its members graduated from Tokyo’s Tama Art University, where they were involved in student protests. Within this intense political setting, their works evoked reflection and meditation, and their presence recalled a re-evaluation of art as a symbol and, moreover, an expression of creation. Nobuo Sekine’s “Phase – Mother Earth” marked for many the beginning of the movement. The work consisted of a cylindrical hole dug into the ground with its excavated earth compacted into a cylinder of exactly the same dimension. Sekine here outlined his exploration of topology, an investigation of space in which the topological shape is not seen as measurable but rather as a “thing” that morphs in reduction and extension. In a fusion of West and East, Sekine employed Western mathematics and Eastern philosophy such as Zen.

At odds with the art world structure today, the works of the Mono-Ha embraced the ephemeral. After their exhibitions or performances, a lot of the works were often completely destroyed. Both artists and collectors were unable to preserve them, which makes the works of this movement incredibly rare and of iconic status.

Tribute to Mono-Ha at Cardi Gallery London.

Tribute to Mono-Ha at Cardi Gallery London.

Artist Lee Ufan.

Tribute to Mono-Ha at Cardi Gallery London.

Tribute to Mono-Ha at Cardi Gallery London.

Noboru Takayama, Yuusatsu, 1973.

Nobuo Sekine’s, Phase – Mother Earth, in 1968.

Nobuo Sekine’s, Phase – Mother Earth, in 1968.