Marisa Merz: the woman in Arte Povera

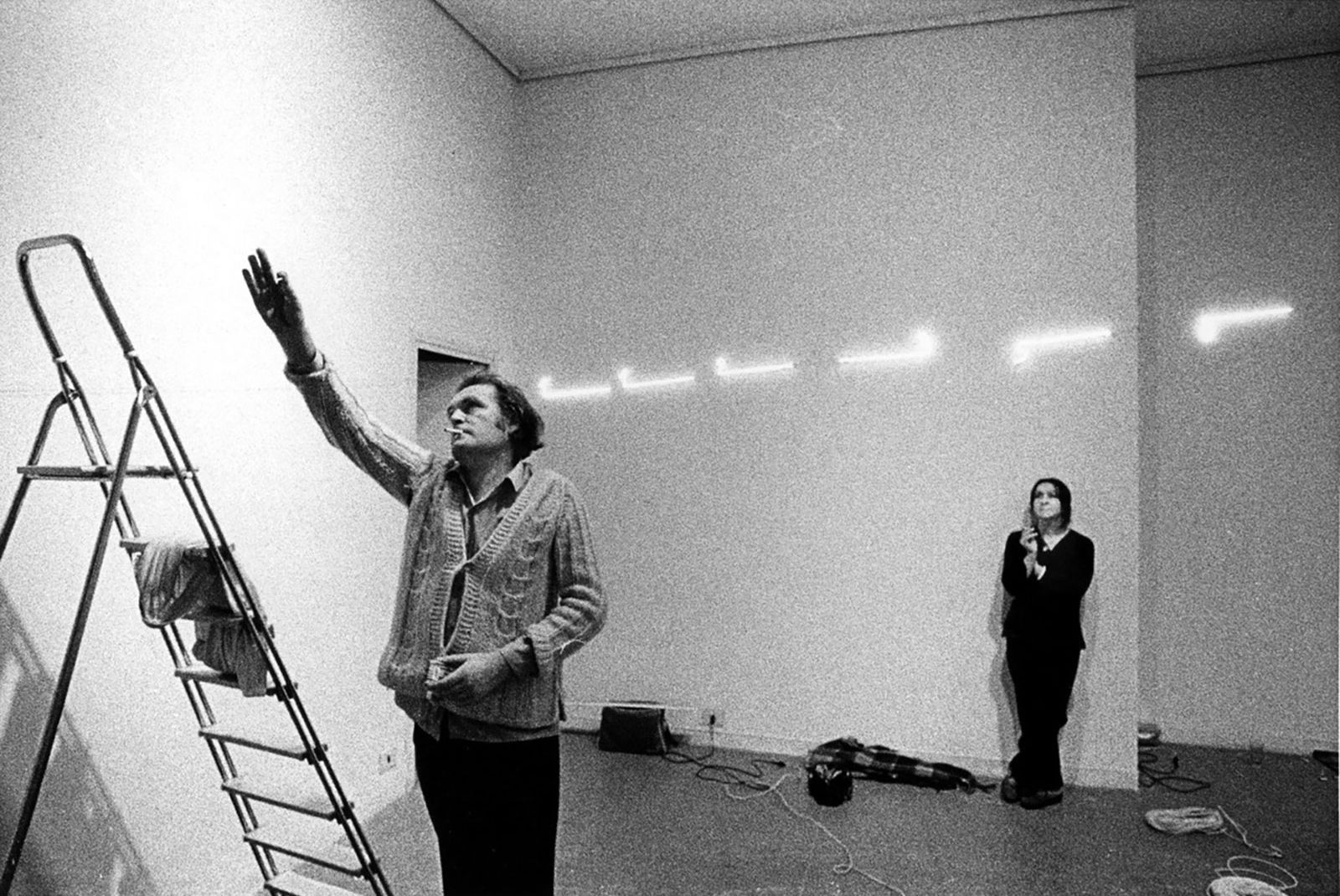

Marisa Merz working with Mario Merz at the Galleria L’Attico in 1969

“When we say “beautiful” we are alive”

The legacy of Turin-born artist Marisa Merz is often defined by her exceptional presence within the male-dominated Arte Povera movement. Alongside its key figures, Merz is recognised as one of its most influential protagonists, and most notably as the sole woman ever associated with the group’s activities. Married to Mario Merz, the duo is remembered for their incredibly collaborative partnership that resulted in many renowned bodies of works. Since the turn of the century, however, her individual practice stood increasingly in focus as her artistic career finally established itself beyond the associations to Mario Merz.

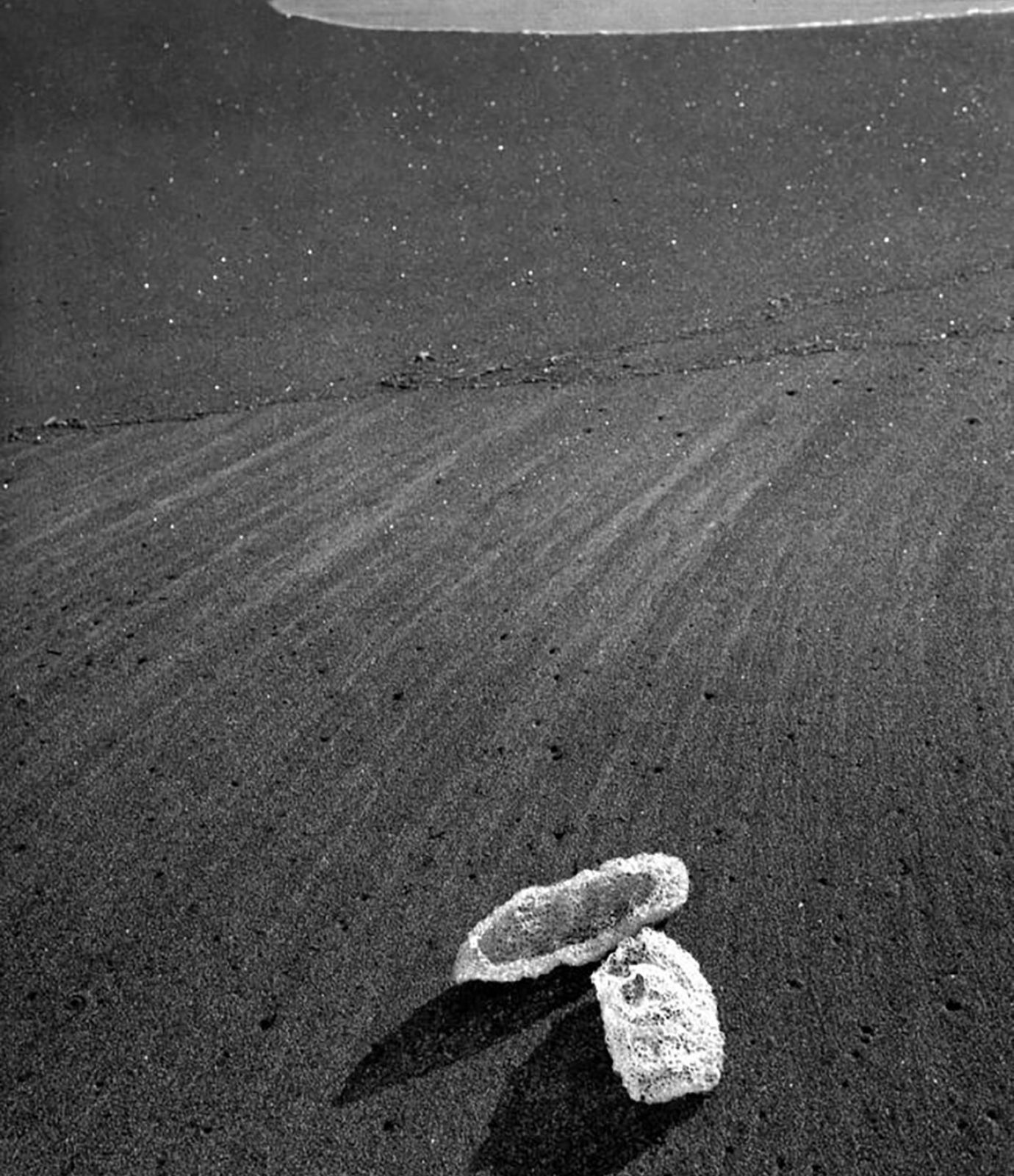

Marisa Merz “Scarpette (Little Shoes)” (1968)

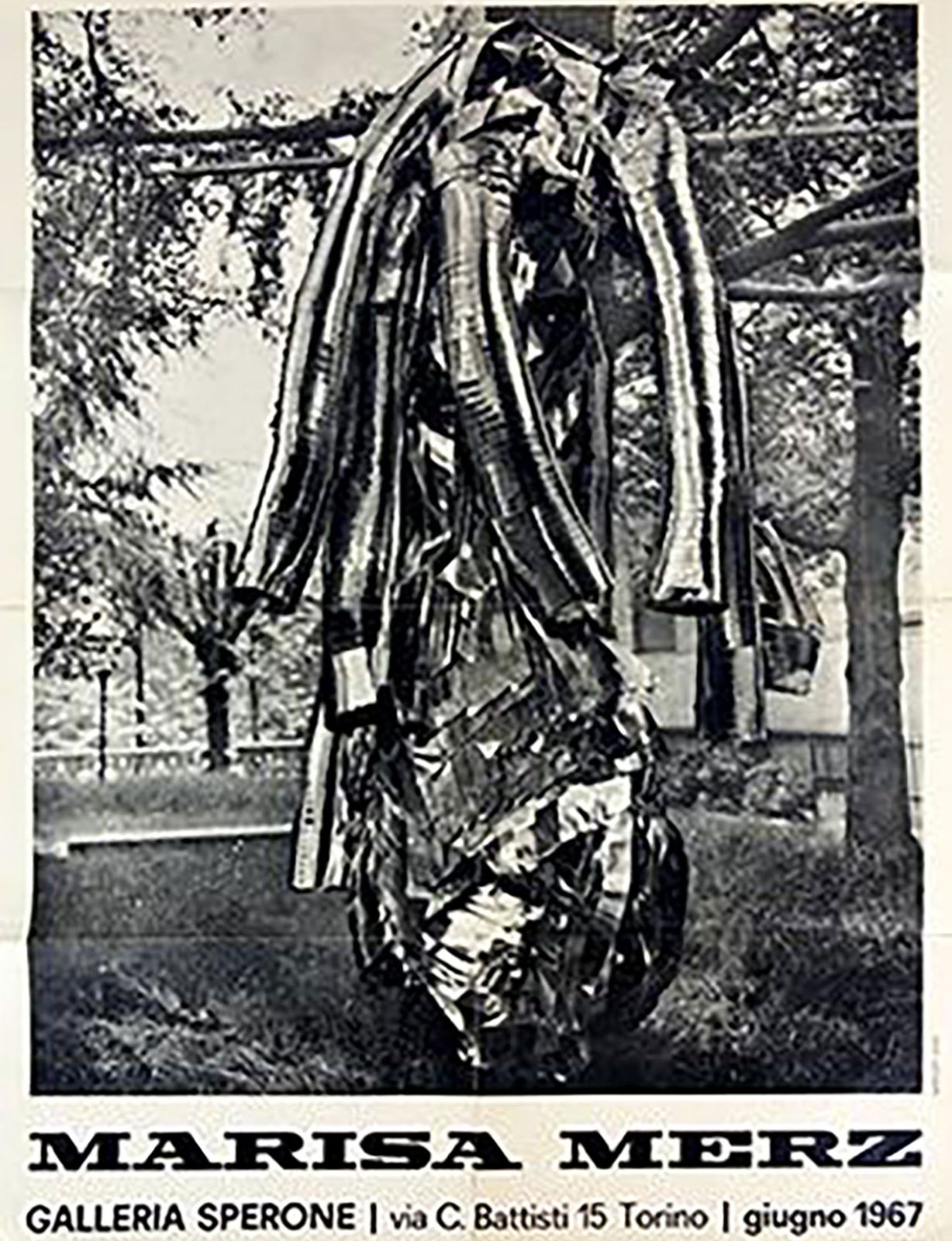

In Italy’s mid-1960s when the arts were entirely male-dominated, Turin-based artist Marisa Merz asserted herself within an avant-garde that trail-blazed new ideas and forms of art-making. Experimenting with inventive “poor” materials, she was known for her minimalistic body of work that included both sculpture and painting, embodying abstraction, as well as figuration. At her first exhibition in 1967 at Gian Enzo’s gallery “Galleria Sperone” in Turin, Merz presented a site-specific, floating installation hung from the ceiling, entirely made of folded aluminium strips. The biomorphic structure is regarded as one of the strongest works of this era and its particular genre. At the time, she created this work in her home, a small apartment that the artists shared with her husband and artistic colleague Mario Merz. Together they shared their living space as studio space in which both of their remarkable fifty-year careers took off.

Following her artistic debut in 1967, Merz quickly earned herself cultural recognition and began exhibiting more frequently. Her career developed alongside the developments of the Arte Povera movement, founded by art critic Germano Celant. At his landmark exhibition “Arte Povera + Azioni Povere” in Amalfi, Southern Italy, Celant brought together an essential group of artists that challenged the status quo of traditional, contemporary art-making of the time. According to Celant, the “Poveristi” denounced the institutionalised high culture by employing “poor” material as their medium, replacing traditional elitist resources such as bronze or marble. In Amalfi, both Marisa and Mario Merz participated in this monumental happening that would see the beginning of one of Europe’s most influential avant-garde post-war movements. Marisa presented “Scarpette (little shoes)” a striking, yet delicate intervention on the exhibition’s beach site. A pair of ballerina-like slippers that resemble the structure of natural sea sponges, but are made of synthetic nylon and copper wire. Recalling a fairy-tale-like spirit, referencing Cinderella’s glass slipper, Merz’s pair is placed dangerously closed to the sea, waiting to be swept away at any moment.

Exhibition Invite “Galleria Sperone”, 1967

Exhibition Invite “Galleria Sperone”, 1967

Marisa Merz in her home kitchen with “Living Sculpture” installed

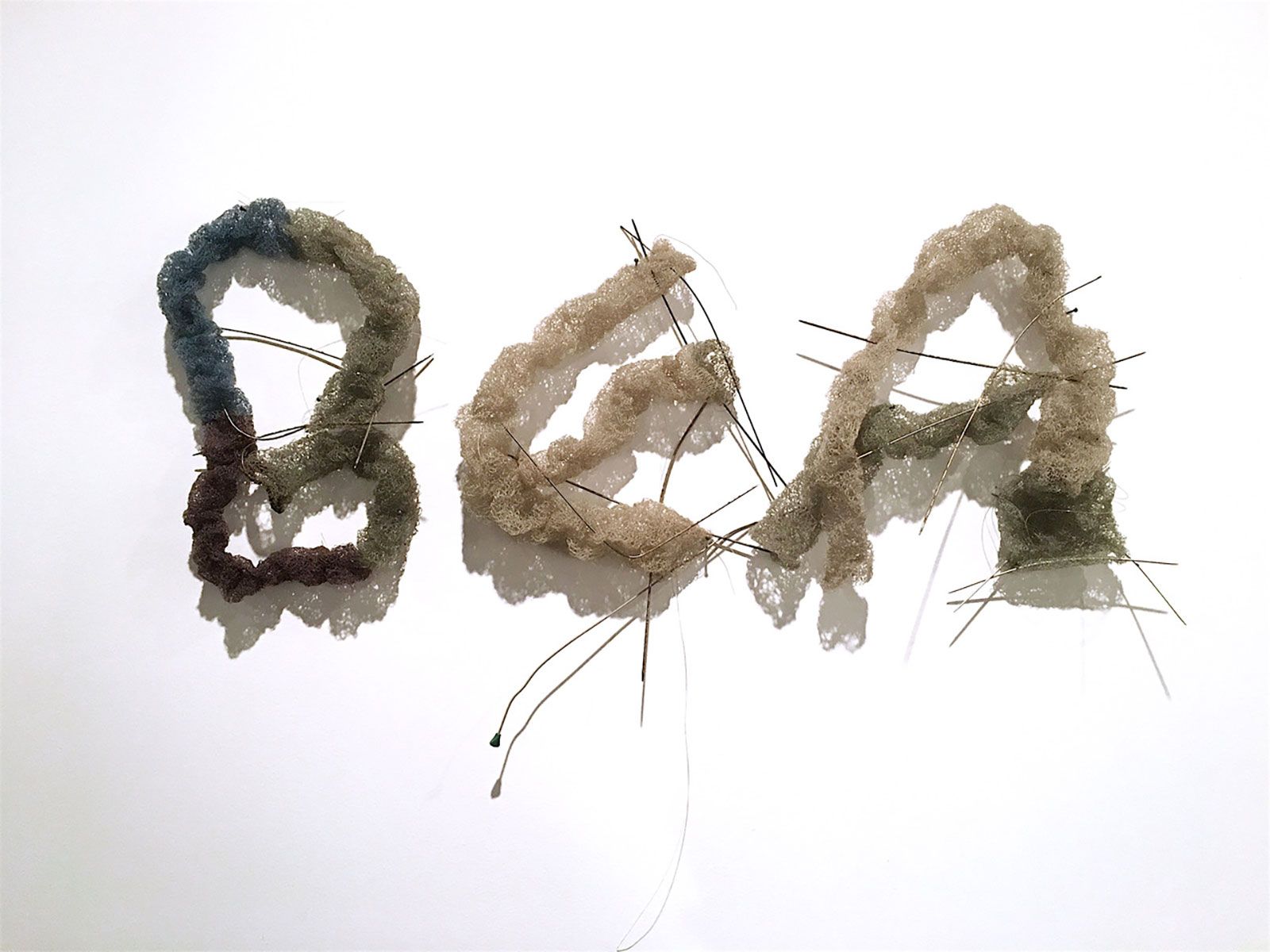

Marisa Merz “Bea” (1968)

Very little is known about Marisa’s personal life prior to her marriage to Mario Merz. Her father worked as a factory worker for Fiat in Turin, where she grew up and studied classical ballet. Working as a model for the figurative painter Felice Casorati, she started to socialise in the city’s artistic circles when she met Mario Merz. Within a year they married, and Marisa became pregnant with their daughter Beatrice Merz, who was born in Switzerland where the family lived for three years. Upon their return to Italy they decided to commit to becoming practising artists in the Turin art scene.

Marisa Merz “Untitled” (1966)

Marisa Merz “Living Sculpture (part.)” (1966)

Much of the spirit of Germano Celant’s Arte Povera is directly connected to the Merz family. Celant’s fundamental writing “Arte Povera: Notes for a Guerrilla War” was conceived and written in their small kitchen in their Turin apartment. The prominent art critic once described Marisa’s oeuvre as a portrait which stands in constant reflection of her personal life, deeply intimate stories that are told through works such as “Bea” (1968) , titled after her daughter. Following Arte Povera’s conceptual principles, the gap between life and art was closed through the utilisation of everyday material and in Merz’s case intensified by her marginalised position within the movement itself. Works such as “Living sculpture”, which originated from her kitchen, subtly navigated a domestic standpoint through a sea of hyper male-dominated studio work. Despite this contemporary contextualisation Merz, like many other female artists of the time, rejected the term feminist or

any different ideological definition of their individual struggle. While the feminine, or feminist rhetoric that many associated with Merz’s practice mainly referred to the materiality of her work in which she often employed traditional craft, this utilisation of “poor” material and the favouring of simplistic resources and processes remain highly evocative of the Arte Povera activities of the time.

For her first participation at Documenta in Kassel Merz had to wait until 1982. Decades later in 2013, she was awarded the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale. Although exhibited regularly and honoured amongst the connoisseurs of the Arte Povera, Merz’s first big solo exhibition would only inaugurate in 2017 when the Met Breuer dedicated a large-scale retrospective to her life’s work. In light of this event, art critic Peter Schjeldahl proclaimed her to be the superior Arte Povera artist to contrast her male counterparts’ often intellectually overloaded works with a lightness and unique magic. Her legacy reminds the art world in its various entities that many marginalised perspectives within art history remain to be told and accounted for.

“I’m not interested in power or in career; only myself and the world interest me. I can do little, very little. I am battling against malice and competition. I cannot escape the reality I see.”

“There has never been a separation between my life and my work”

Marisa Merz with Mario Merz at Galleria Francois Lambert, 1971

Beatrice, Mario and Marisa at the 37th Biennale di Venezia 1976