Mapping the cosmos: Alighiero Boetti

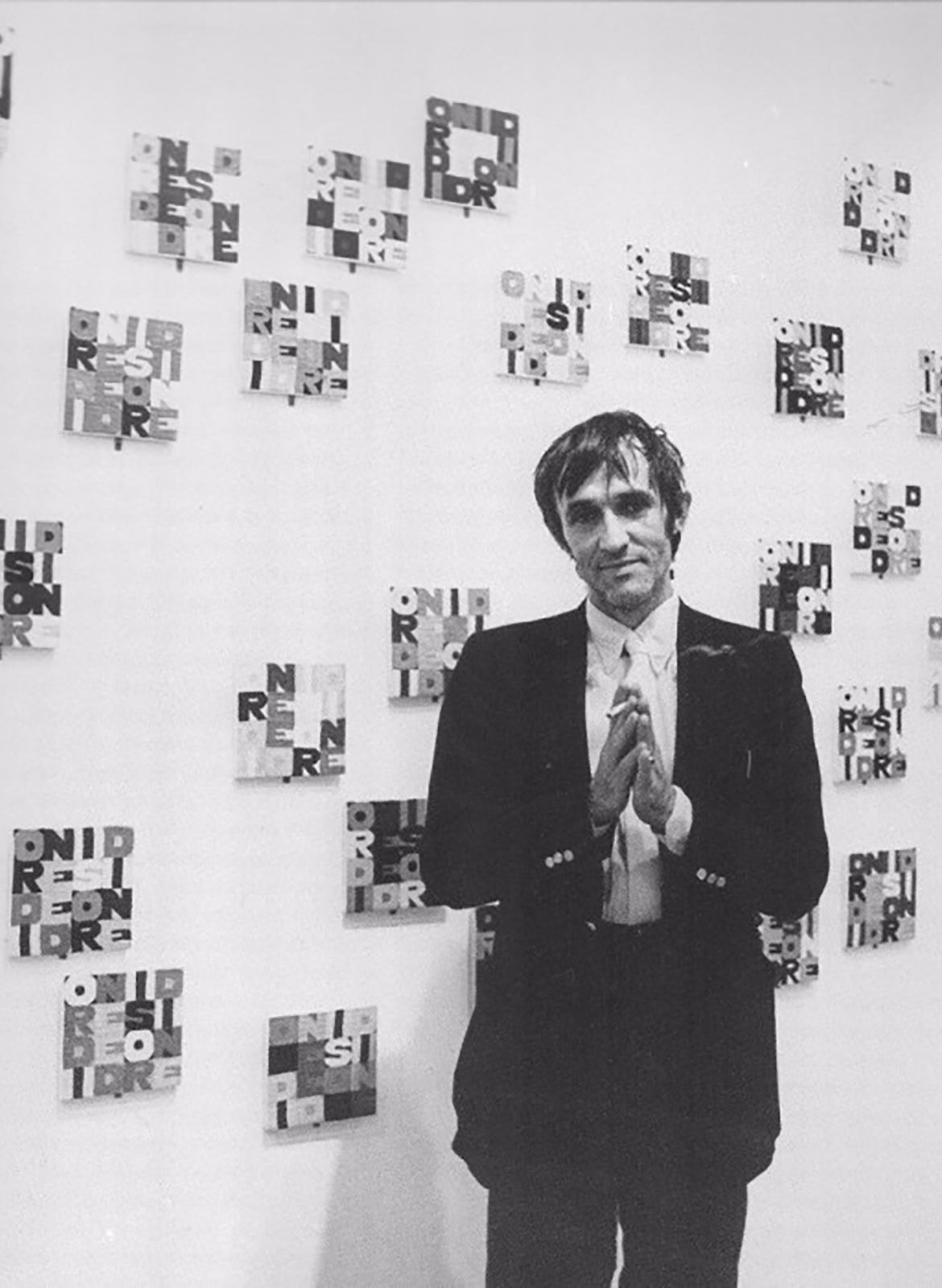

Alighiero Boetti Galleria Toselli, 1970 Photo © Paolo Mussat Sartor, Torino

“First of all I prefer thought. This is the basic thing. I really think manual skill is secondary. . . It’s taking things from reality. Everything, however small and humble, always has a beginning and stems from reality.”

This week Italian artist Alighiero Boetti would have turned 80 years old. His ambivalent life and artistic practice remain fundamentally important as one of the most important exponents of conceptual art and as a leading figure of the Arte Povera movement. Saturated by the continued exploration of opposites, Boetti’s oeuvre traces the tension between positive and negative, order and disorder, or east and west. Introducing new ways of making art the artist promoted an emerging realisation amongst the Arte Povera group that art can be made of anything. His unique interest in the visual investigation of language, mathematics, process and humour, however, distinguished him greatly from his peers and solidified a spectacular artistic legacy.

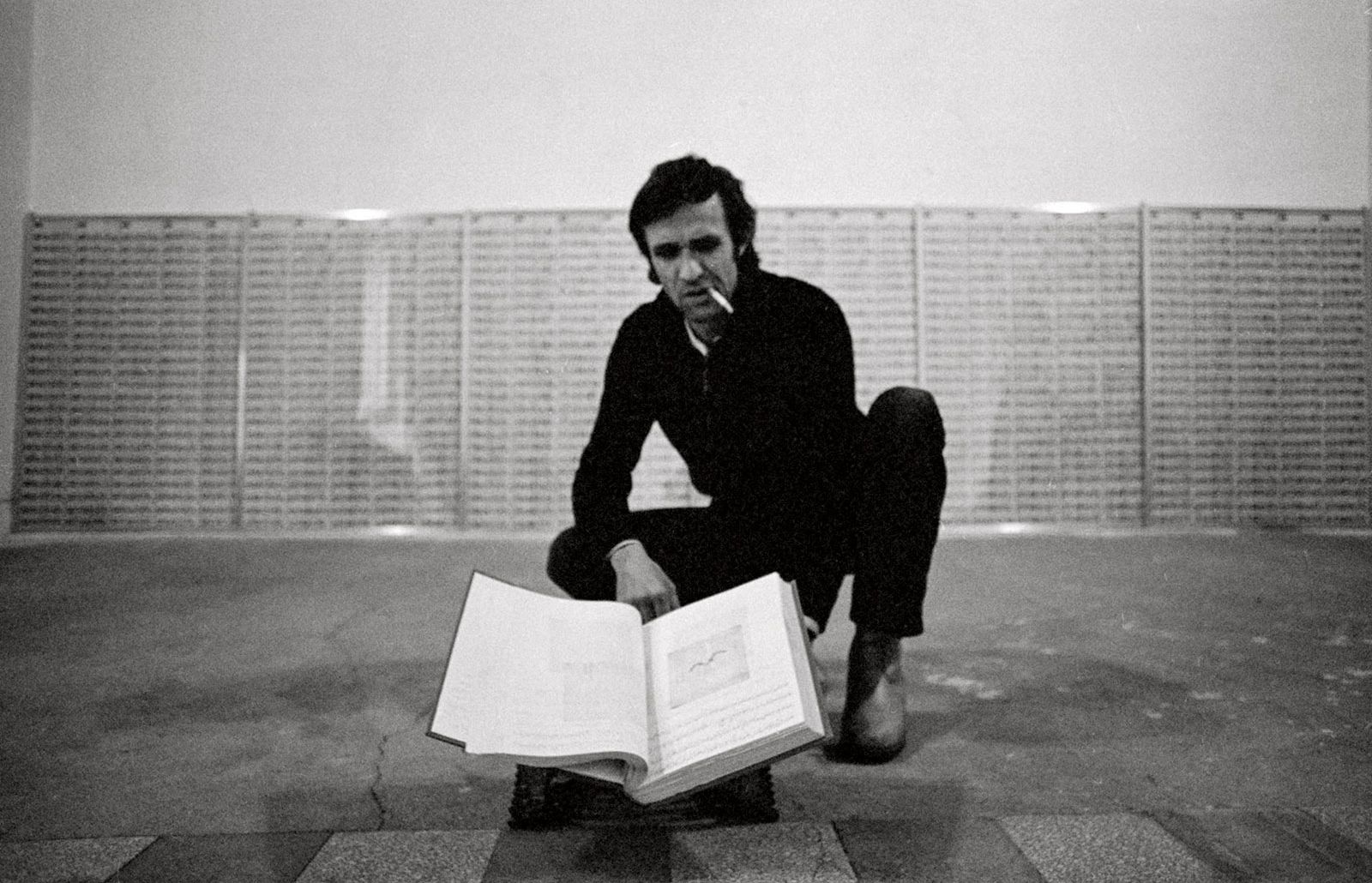

Alighiero Boetti installing “720 letters from Afghanistan” at the Kunsthalle Basel, 1978. Foto from Gianfranco Gorgoni

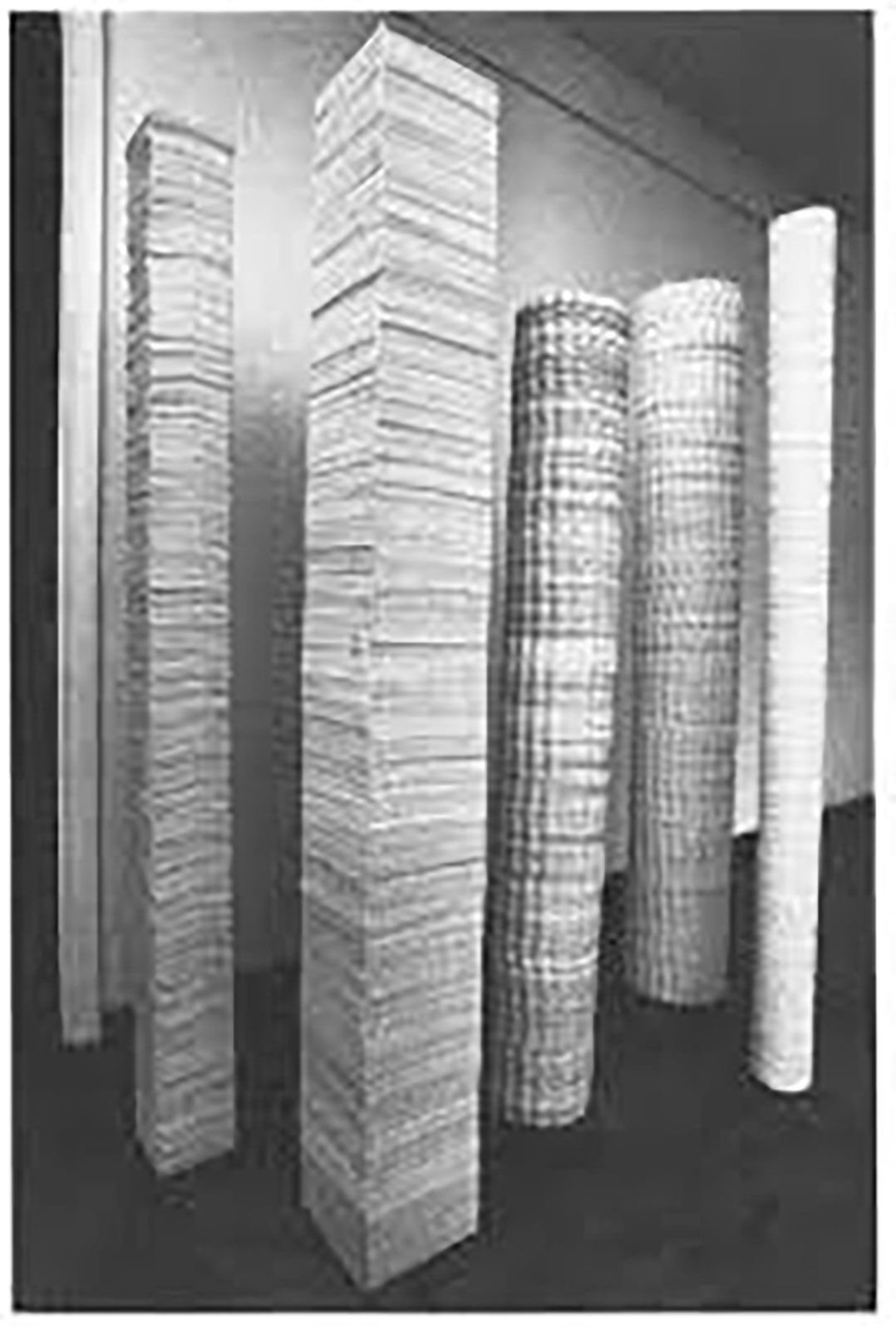

Alighiero Boetti, “5 elementi” (1968)

Alighiero Boetti working on “Collonna”

As the son of an attorney and violinist, Alighiero Boetti was born into a wide-ranging field of creative influences that include philosophy, alchemy, mathematics and music. Aside from his passion for the arts, the young Boetti emerged as artist entirely self- taught, dropping out of University in Turin to completely devote himself to becoming an established artist. Exhibiting alongside peers such as Lucio Fontana, Michelangelo Pistoletto, Giulio Paolini, Jannis Kounellis and Mario Merz, Boetti became associated with the Italian post-war movement Arte Povera.

“Some of the best moments in Arte Povera were hardware shop moments.”

Within his artistic practice, Boetti often referred to himself with the pseudonym “Alighiero e Boetti”, in English “Alighiero and Boetti”. Less of a word game, this given title represented a serious reflection and expression of a confrontation with his identity. The added Italian “and” directly suggested an implication of two separate identities in communication and contrast with each other. This duality reappears in the various body of works, but specifically in the form of the visual representation of orderly and disorderly forms.

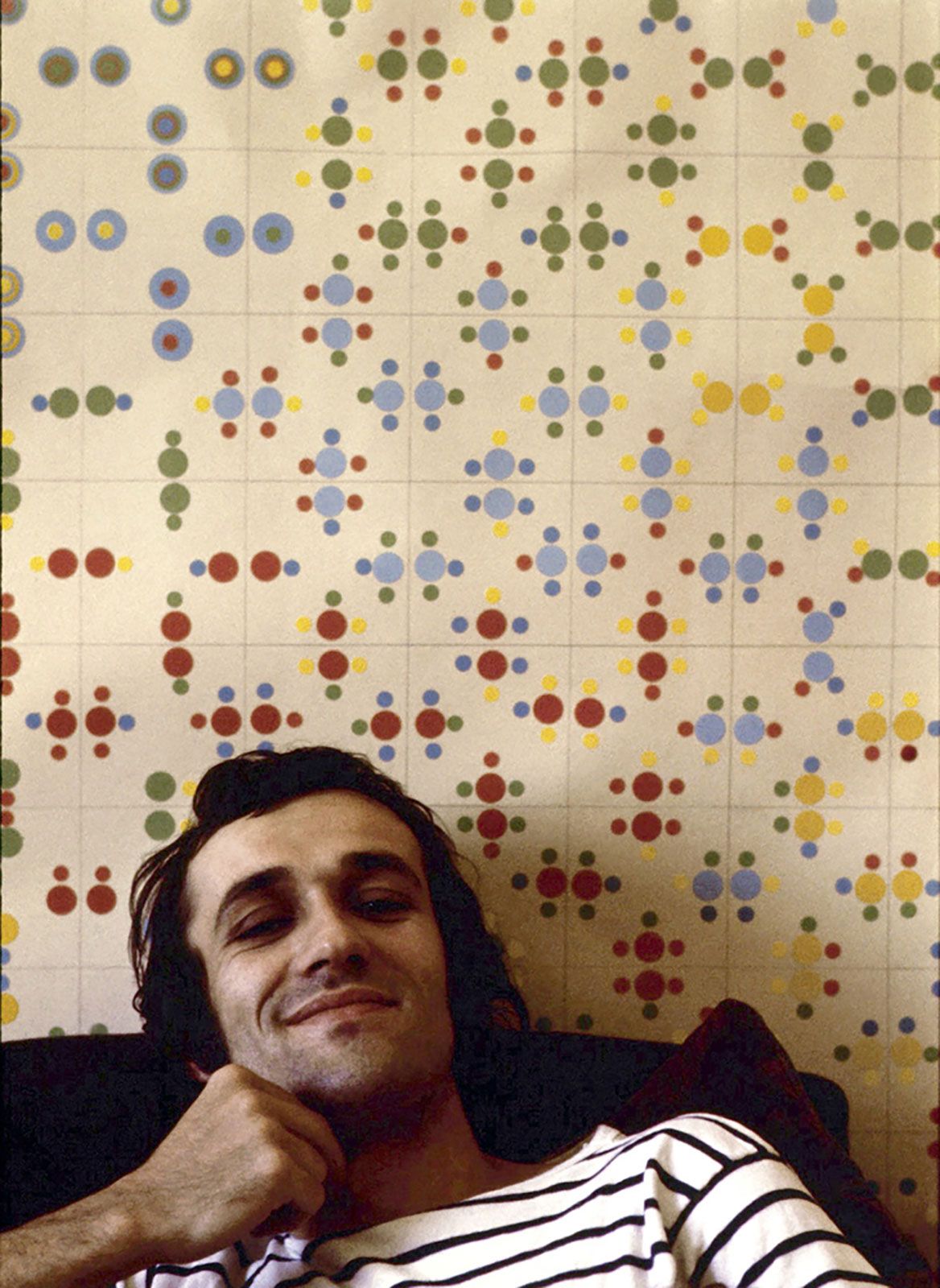

Alighiero Boetti Galleria Toselli, 1970 Photo © Paolo Mussat Sartor, Torino

“I have done a lot of work which presents a visual disorder that is actually the representation of a mental order. It’s just a question of knowing the rules of the game. Someone who doesn’t know them will never see the order that reigns in things. It’s like looking at a starry sky. Someone who does not know the order of the stars will see only confusion, whereas an astronomer will have a very clear vision of things.”

Alighiero Boetti working in his studio in Rome. From the book “Boetti by Afghan People”, RAM Publications, September 2011, Photo by Randi Malkin Steinberger, Courtesy Fondazione Nicola, Milan

Afghan craftswoman working. From the book “Boetti by Afghan People”, RAM Publications, September 2011, Photo by Randi Malkin Steinberger, Courtesy Fondazione Nicola, Milan

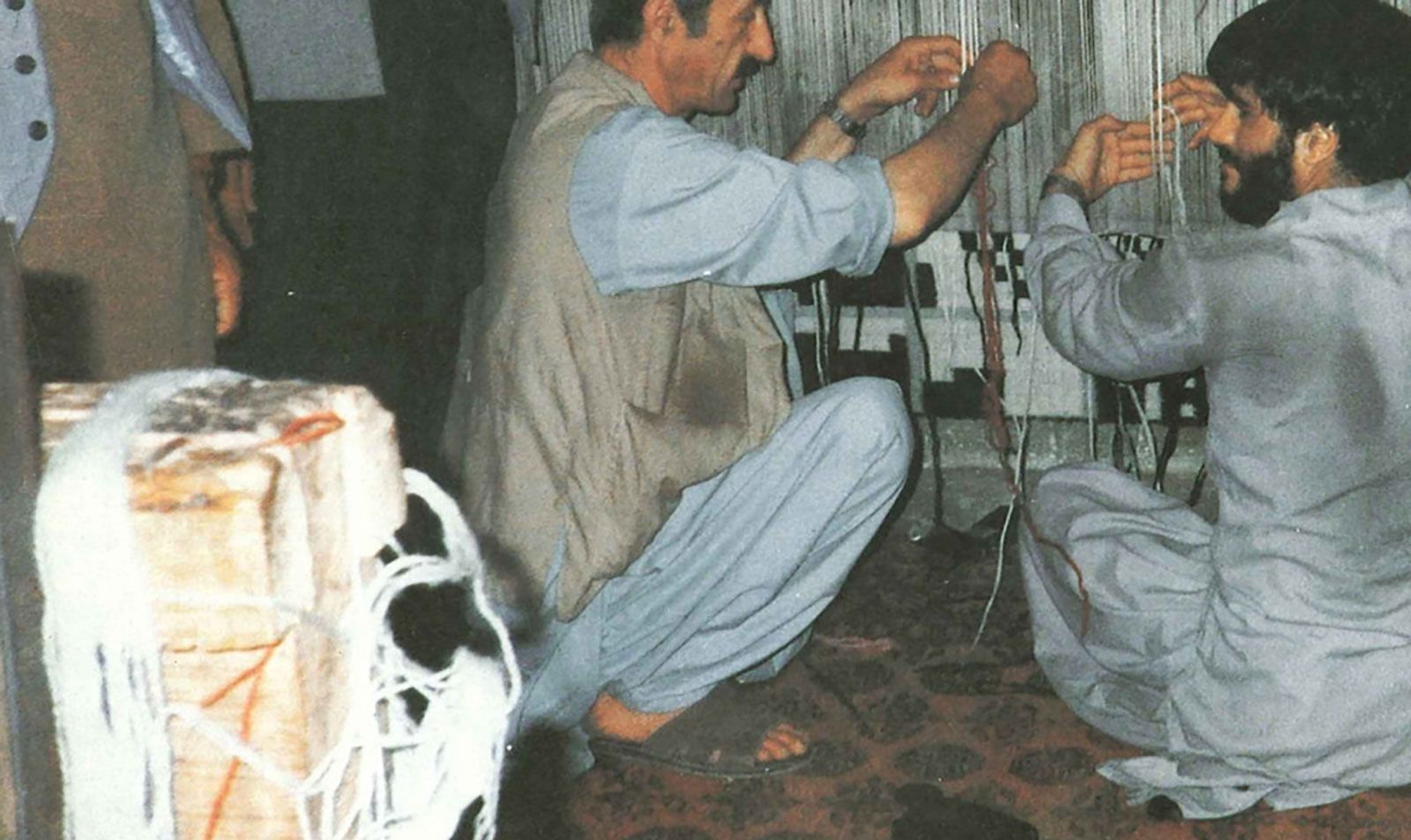

Boetti’s works across all media trace a particular reading of the world. Saturated by his worldly experiences gathered during his travels across the globe, the artist introduced his nomadic spirit into both subject and medium. At the beginning of the 1970s, Boetti travelled extensively to countries such as Ethiopia, Guatemala, Pakistan or Sudan. Afghanistan however, would manifest itself as the most influential place for Boetti’s practice as he developed an incredibly paramount affection to its people and history. Years of war, social and political turmoil instigated the artist to explore these matters by investigating them through the visual properties of the map. These hand-embroidered maps have since become one of Boetti’s most recognisable motifs and most important body of work. Upon his first visit to Afghanistan, the artist started to commission local weavers to create these maps, at times using the traditional “Suzanni” embroidering technique.

From 1971 to 1994 Boetti would collaborate with the Afghan craftswoman. Laying out the design with its abstract and figurative elements comprised of symbols, geographical maps, language and text on canvas, Boetti invited the weavers to finalise the colouration of their embroidered. Within the first decade of production, 150 “Mappe” of various size and colour were created. The maps outline ten years of global political tension and shift. A passage of time that is visually represented in the subtle variations between each map demonstrates the prevailing global nationalism in the form of borders and flags.

“Peshawar”, April 1993. Pakistani men working on a kilim for the show “Alighiero Boetti De Bouche A Oreille” (Magasin, Grenoble, 1993-1994). Courtesy Adelina von Fürstenberg

“I considered traveling from a purely personal, hedonistic point of view. I was fascinated by the desert… the bareness, the civilisation of the desert.”

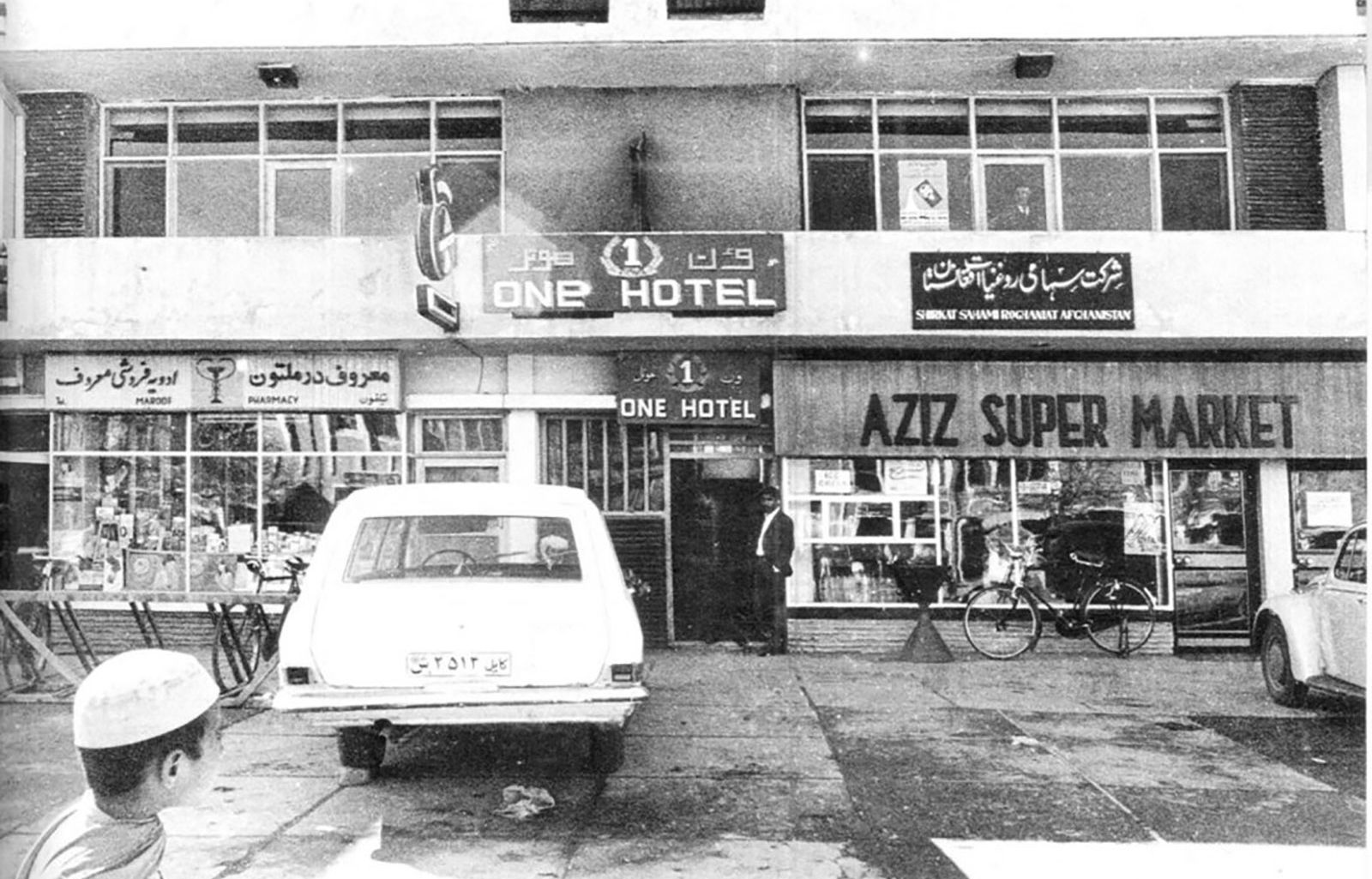

The various written manifestations that frame the maps are indicative of Boetti’s wide reaching influences, at times declaring that the tapestry was created during the time of Pablo Picasso’s death or communicating philosophical thoughts such as “Between ten and twelve, the eleven is like Afghanistan…impossible to double, to trace, a last stratosphere.”. Boetti’s favourite number, 11, appears in many of his works, as well as his personal life. In Kabul, the artist ran a hotel for a few years that had exactly eleven rooms to book, one of which, room 11, became Boetti permanent stay whenever he found himself in the country.

His deep connection to the country went beyond travelling and exploring Afghan life as an outsider. During his first travels to Kabul in 1971, he befriended Gholam Dastaghir, whose dream it had been to run his own hotel in the city. Boetti decided to work with him, renting the building for five years and running it together, calling it “One Hotel”. Up until 1979 when the border to Afghanistan permanently closed due to the Soviet invasion, Boetti regularly worked and travelled through the country. His hotel, which eventually closed remained in many ways a precursor of future art practices in which the medium of the artwork becomes even more ambivalent, existing within the social context between human and human. In Boetti’s words: “Creativity also means opening a hotel.”

One Hotel, Kabul, Afghanistan. 1971–77 Photograph. 9 x 12″ (22.9 x 30.5 cm). Courtesy Archivio Alighiero Boetti © 2012 Estate of Alighiero Boetti/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/SIAE, Rome

Alighiero Boetti at the Kunsthalle Basel, 1978. Foto from Gianfranco Gorgoni