Giacomo Balla and the Futurist Order of things

Giacomo Balla, Speeding Automobile, 1912

Working across multiple genres the Italian Futurists of the 1920s embodied an all-absorbing ambition to promote modernity and futurist ideologies that encompassed a variety of fields ranging from the visual arts to design, music, advertising, fashion and food. Its canonical influence often overlooked due to the movement’s complicated history with fascism, its glorification of war and its inherent misogyny, had despite this an immense influence on art history and the 20th Century. Amongst its most celebrated artists, Giacomo Balla was considered a central figure to the movement. His studies on technology and movement highly informed the Futurist Manifesto and its ideals which to this day evoke a highly saturated avant-garde that existed beyond the visual arts and was moreover considered a lifestyle with an aim to “reconstruct the universe”.

“Indeed, all things move, all things run, all things are rapidly changing. A profile is never motionless before our eyes, but it constantly appears and disappears. On account of the persistency of an image upon the retina, moving objects constantly multiply themselves, their form changes like rapid vibrations, in their mad career. Thus, a running horse has not four legs, but twenty, and their movements are triangular”. (Giacomo Balla)

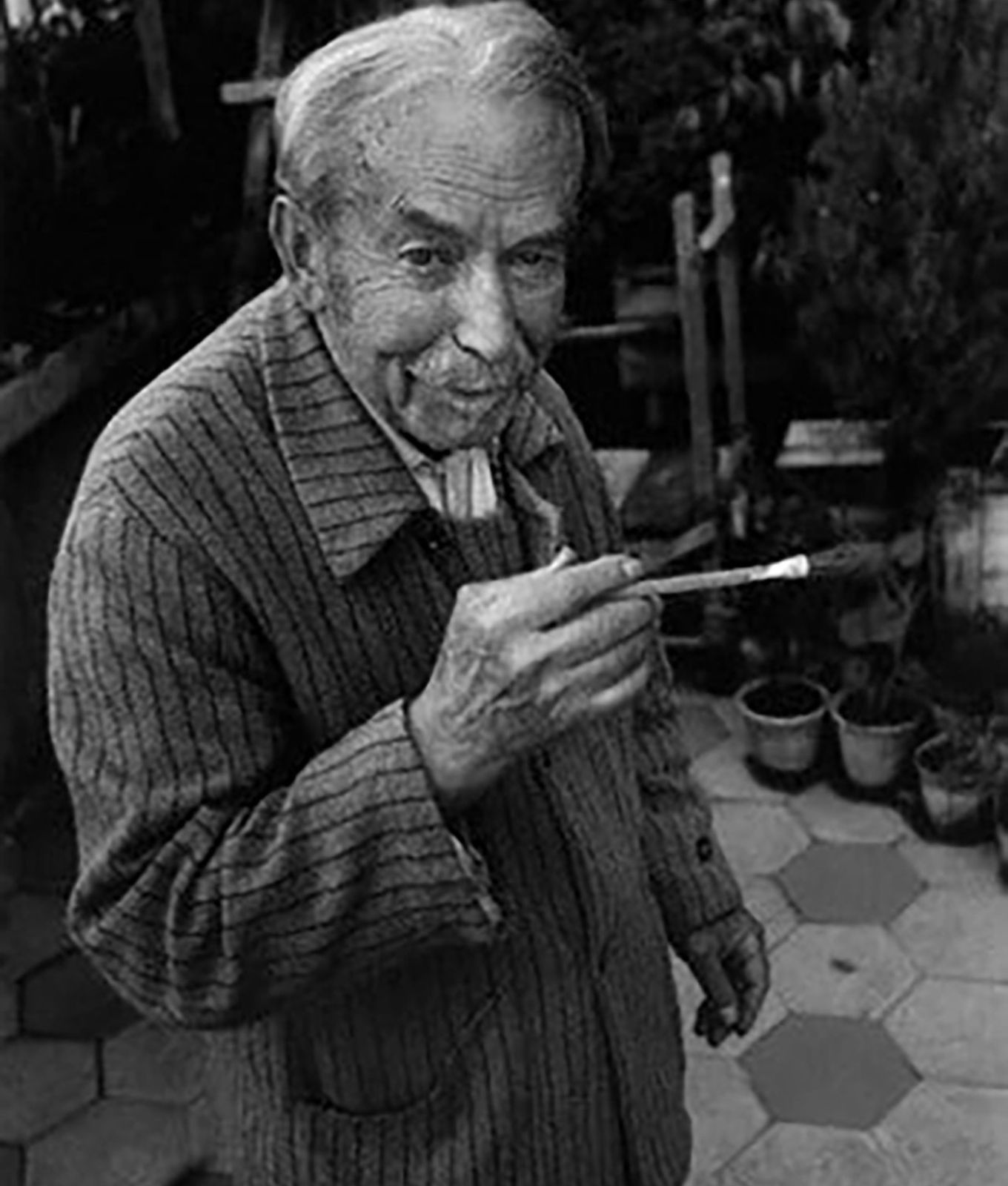

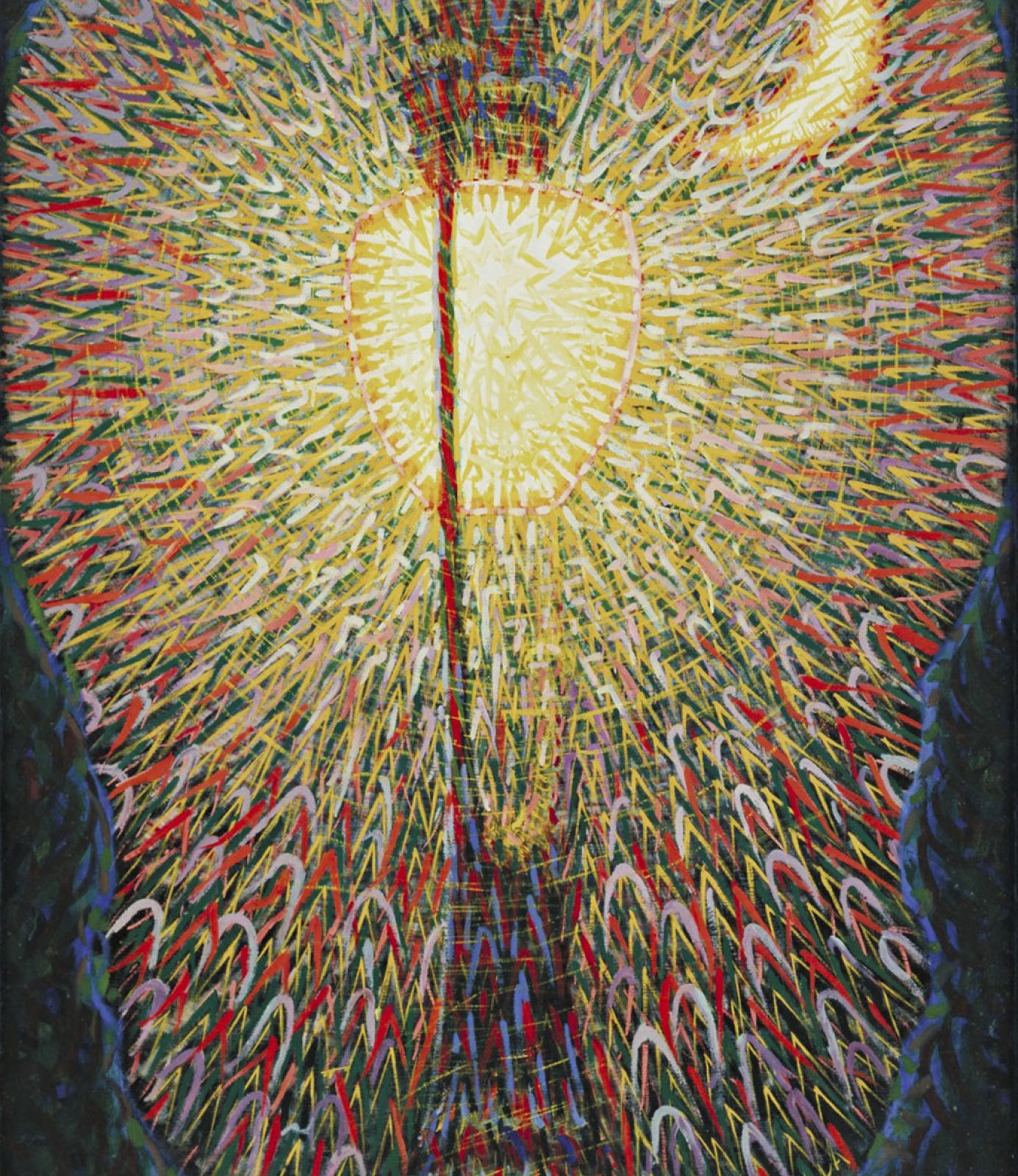

As a key figure of Italian modernism, Giacomo Balla (1871–1958) is considered one of the most important representatives and founders of Italian Futurism. Born in Turin, the artist attended the Accademia Albertina di Belle Arti and the University of Turin, before relocating to Rome in 1895. Balla worked across multiple artistic genres such as illustration, caricature and portrait painting. In 1899, following his Venice Biennale participation and the exhibition “Esposizione internazionale di belle arti” in Rome, Balla began to show regularly in established galleries around Italy. Informed by Pointillism and Italian Divisionism, his particular interest in light and movement led him to begin instructing Futurists peers such as Gino Severini and Umberto Boccioni. His work “Street Light” (1909), displaying the image of an electric lamp, has been accredited as the very first Futuristic painting. Artificial light and mechanical movement soon became of primary interest for the painter. Balla’s contribution to the Futurism movement reached its peak however when he, alongside artists such as Carlo Carrà and Luigi Russolo signed the monumental second Futurist Manifesto in 1910.

The artist Giacomo Balla

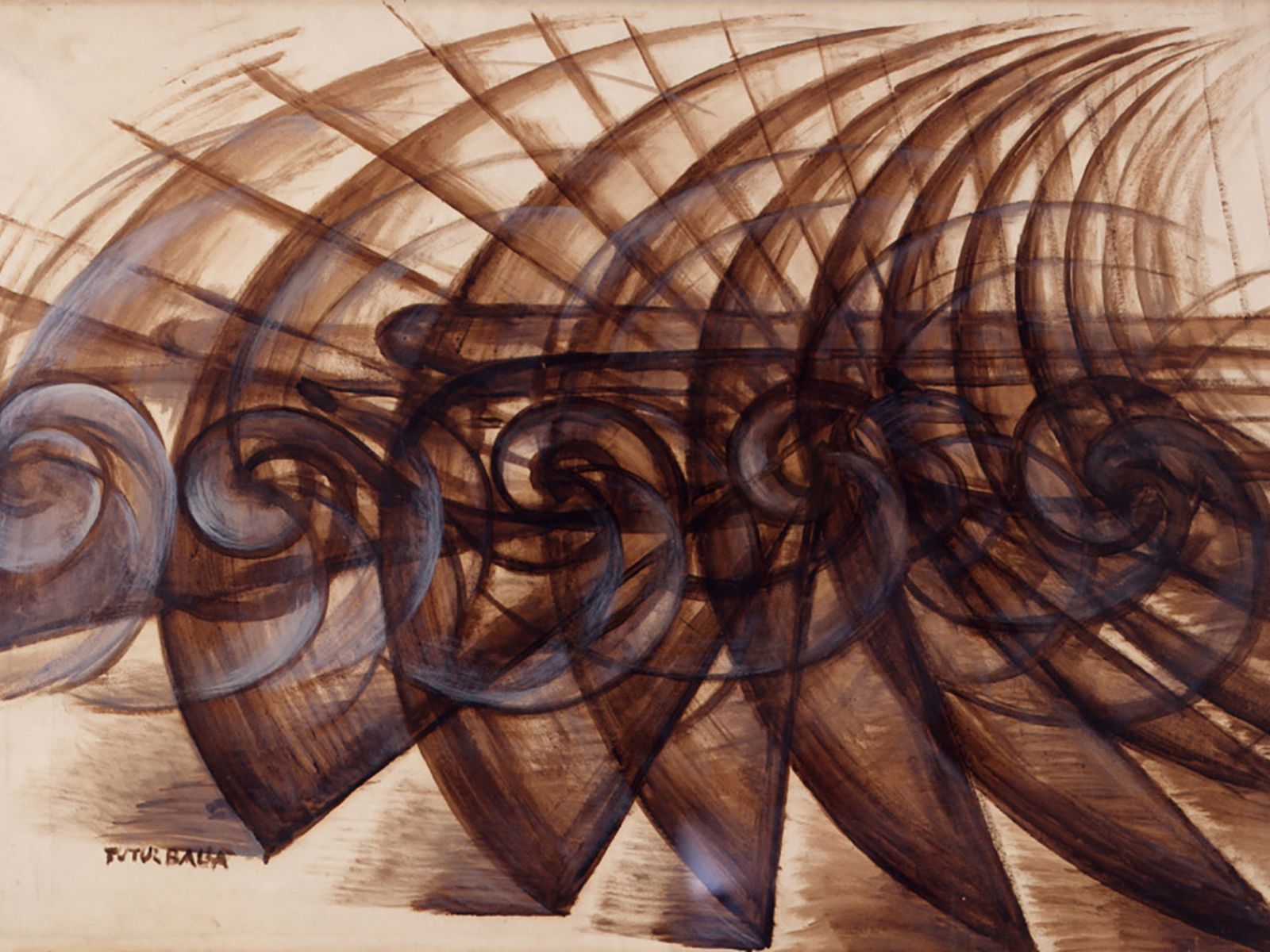

Detail of Giacomo Balla, Velocità di motocicletta, 1913

Detail of Giacomo Balla, The street light, 1909

“We want to fight ferociously against the fanatical, unconscious and snobbish religion of the past, which is nourished by the evil influence of museums. We rebel against the supine admiration of old canvases, old statues and old objects, and against the enthusiasm for all that is worm-eaten, dirty and corroded by time; we believe that the common contempt for everything young, new and palpitating with life is unjust and criminal.” (Filippo Tommaso Marinetti)

Balla’s oeuvre embodied the driving leitmotif and source of inspiration for the Futurists which was the recognition of the machine as beauty, as something that was heralded as “more beautiful than the Nike of Samothrace”. Part of Balla’s key body of work was a series of paintings and drawings which explored the visual sensibilities of velocity and mechanical speed. The work “Velocità d’automobile” (1912-14), presented through Cardi Gallery at this year’s Art Basel Miami presentation, is part of this critically important body of work of the Futurism movement. The members declared an exploration and promotion of modernity through the celebration of technology and the demonstration of the machine as an object of beauty.

Giacomo Balla, Velocità di motocicletta (the speed of the motorcycle), 1913

Giacomo Balla, Abstract Speed + Sound, 1913-1914

Balla had established the moving car as a symbol for a modern world, and that was, according to the Futurist Manifesto, “more beautiful than the Nike of Samothrace”. The artist extensively studied the modern vehicle which served as a perfect survey for the formal exploration of mechanical movement and velocity, in light of the theoretical concepts of the Futurists. Forms that embodied the danger and the dynamic of the motor became prevalent in the Futurist aesthetic. Geometric forms such as spirals, fragmented, broken shapes, and dizzying perspectives dominated the canvas of the time.

In an attempt to convey these new dynamic mechanics, Balla deconstructed each skeletal fragment to a purely geometric form. Rectangular lines are superimposed with round shapes of wheels that in dynamic succession are repeated across the canvas. The abstracted automobile is a reoccurring motif in the artist’s oeuvre that not only perfectly encapsulated the Futuristic ideology, but is also rendered pictorially through cubistic influences on form and style. From the motor machine to the coffee machine, the Futurists engaged in the rejection of all that was deemed classical, traditional and not industrial. In 1915 Balla and Fortunato Depero signed another Futurist manifesto titled “The Futurist Reconstruction of the Universe”, declaring a cultural revolution across all parts of society. Inspired by the rapid industrialisation that was sweeping through Europe at the time, Balla and his peers celebrated the industrial city and all its futuristic innovations. They determined that Italy’s culture at the time was in decay, static in its traditionalism. Following the belief that human life would be ultimately liberated and enriched by the everyday presence of art, Futurist concepts often bridged the avant-garde and life, feeding the Futuristic notion of the “opera d’arte totale” (the total work of art).

“We will find abstract equivalents for all the forms and elements of the universe, and then we will combine them according to the caprice of our inspiration, to shape plastic complexes which we will set in motion”.

(“The Futurist Reconstruction of the Universe”, 1915)

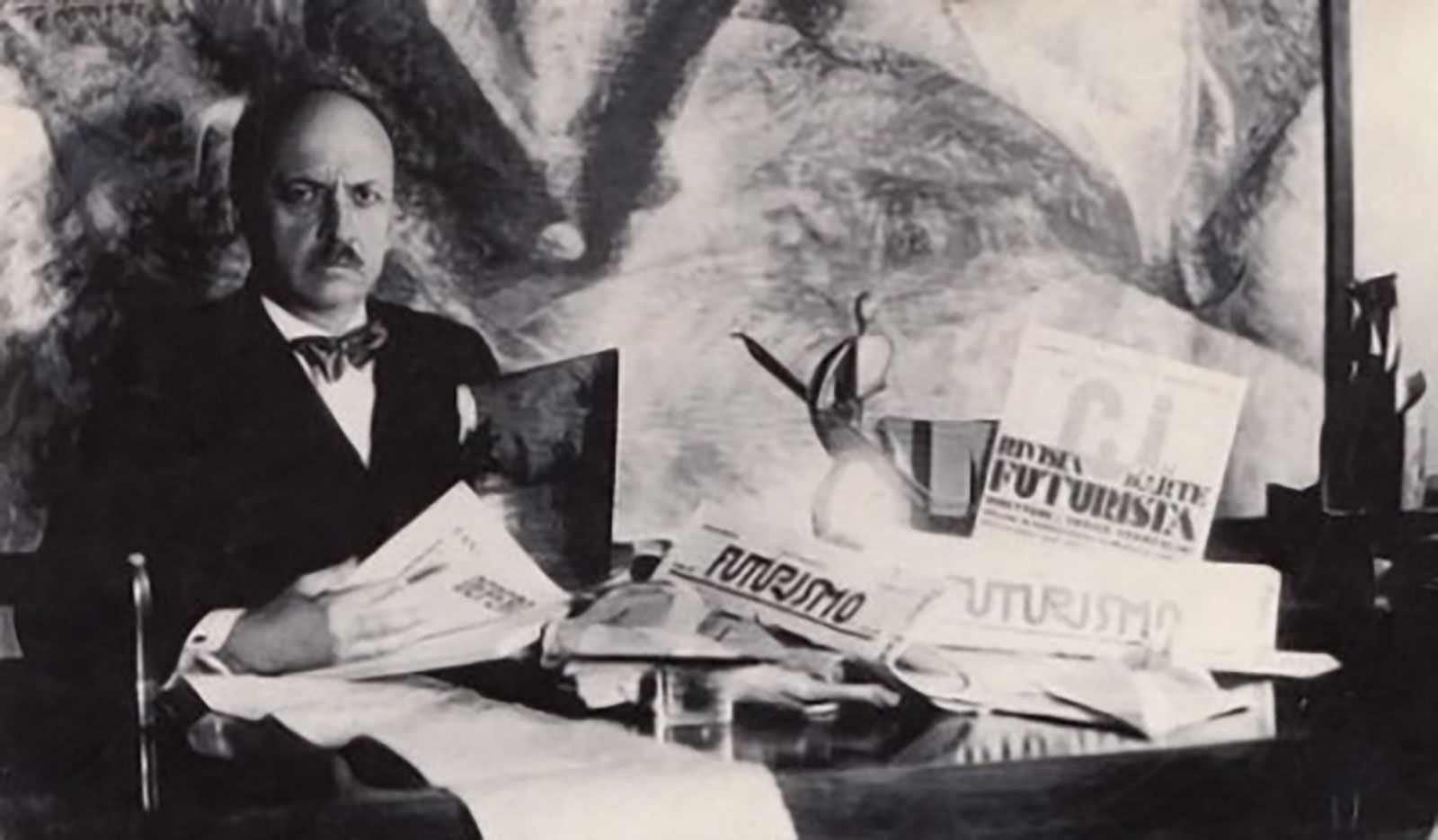

Filippo Tommaso Marinetti

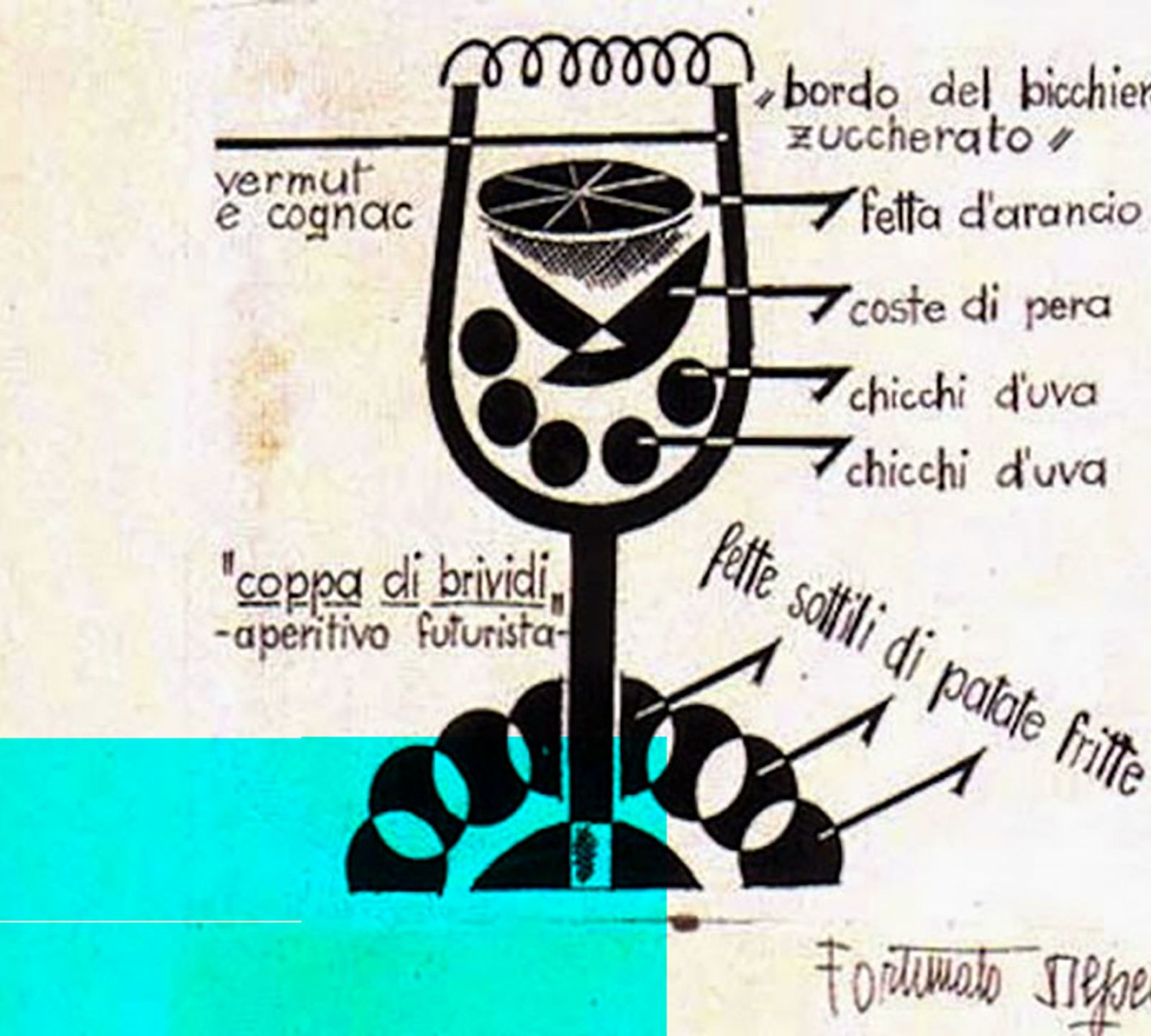

The Futurist cocktail: Coppa di brividi (Aperitivo Futurista)

Filippo Tommaso Marinetti

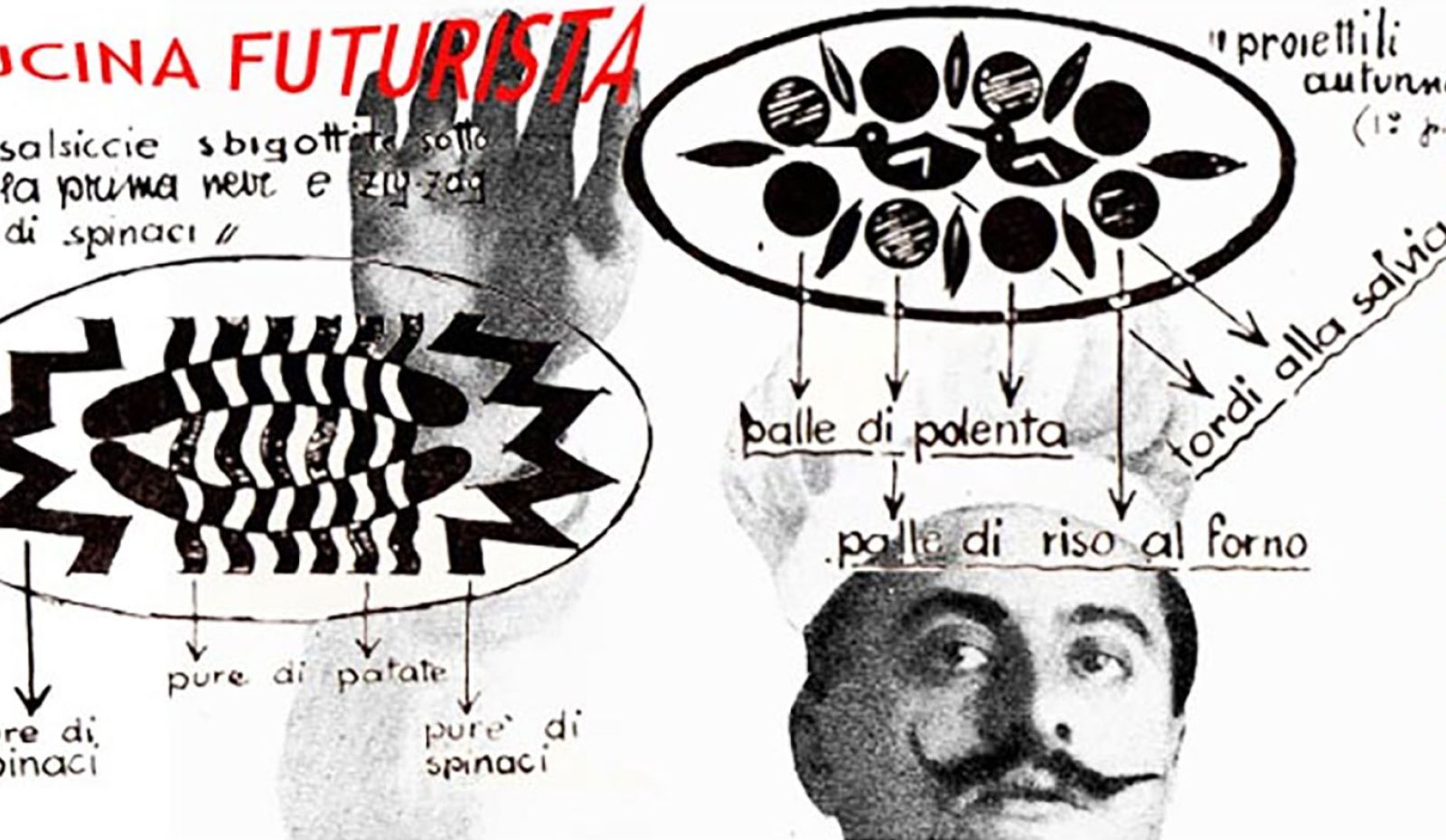

Futurism’s founder and leading figure Filippo Tommaso Marinetti led this cultural revolution which through its influences on decorative art, design and fashion, also impacted the kitchen and Italy’s famous cuisine. Marinetti raged against starchy food, specifically pasta which he found to be the cause of society’s “laziness”. Although this war against pasta proved to be incredibly unpopular, the Futurists efforts to reject traditional Italian establishment across all forms eventually informed the beginnings of gourmet experimentation in the Italian culinary establishment.

Here Cardi Gallery invites you to explore the Futurist Lifestyle beyond its mesmerising art. Experiment with a few of these Futurists cooking guidelines below and prepare an unforgettable avant-garde dinner that will surely interrupt the mundane routine of lockdown dining.

“This futurist cuisine of ours, regulated like the engine of a high-speed seaplane, will seem crazy and dangerous to some trembling passatists: instead, it finally wants to create harmony between the palate of men and their lives today and tomorrow”.

Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, Fillia – “La cucina futurista” (1932)

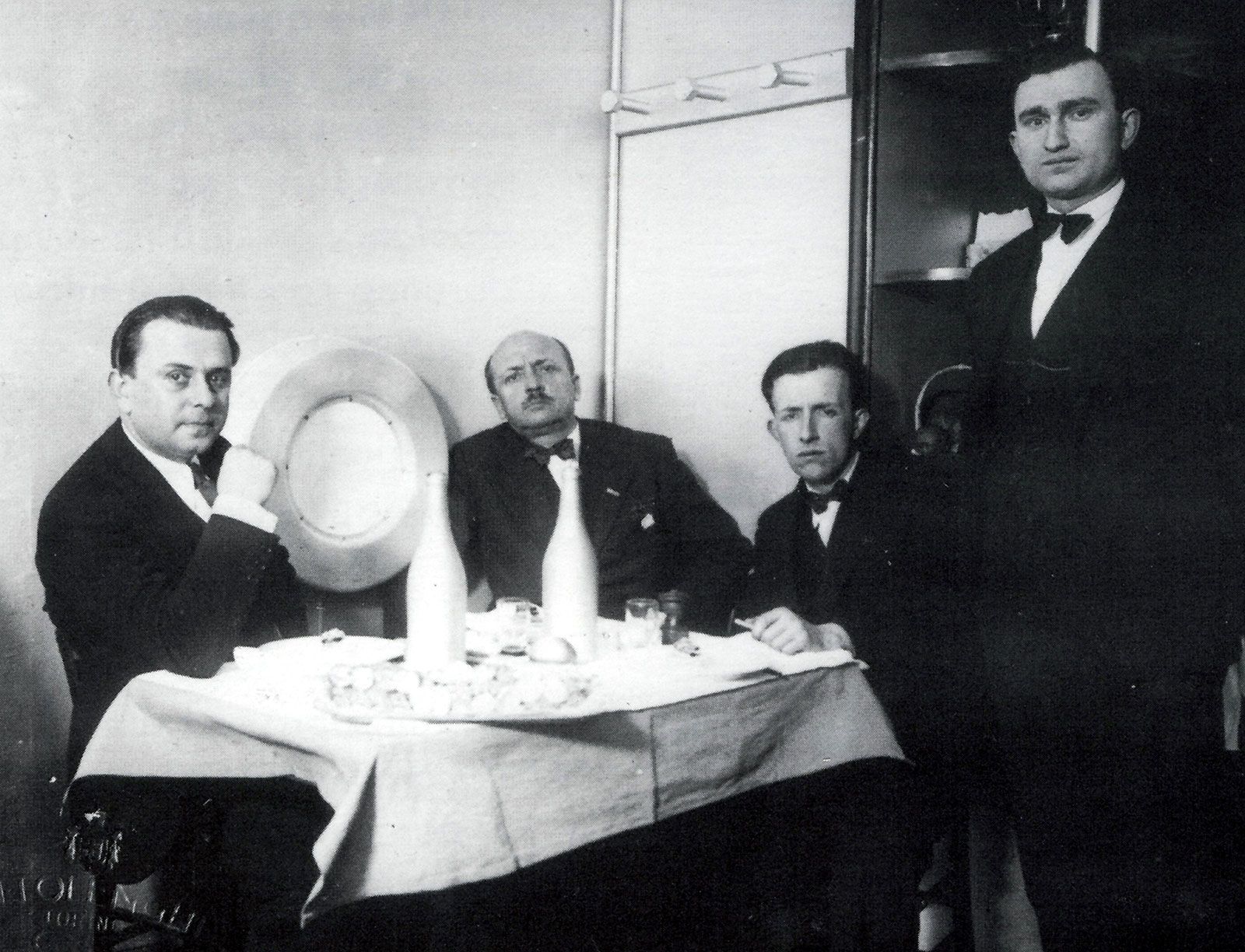

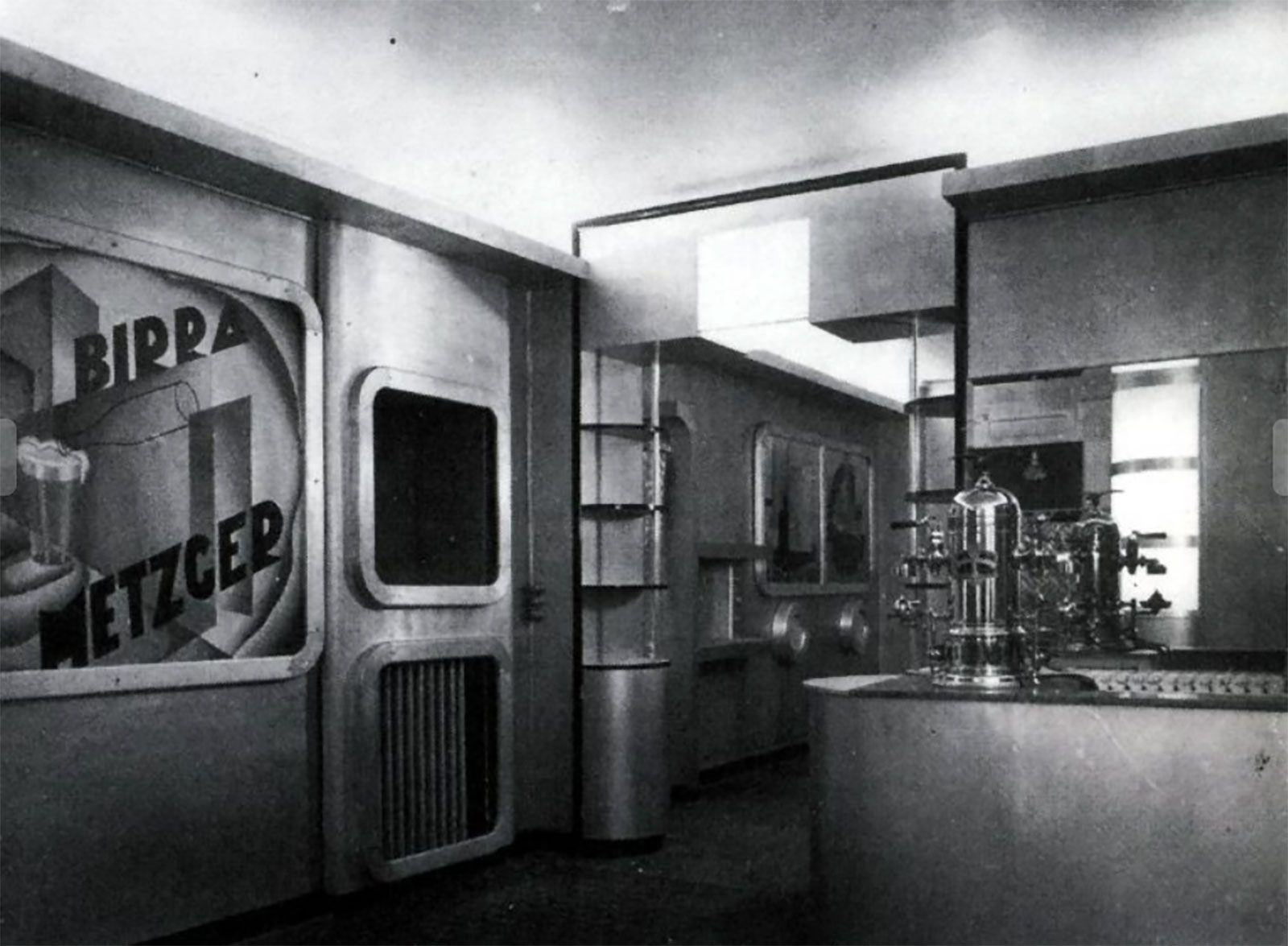

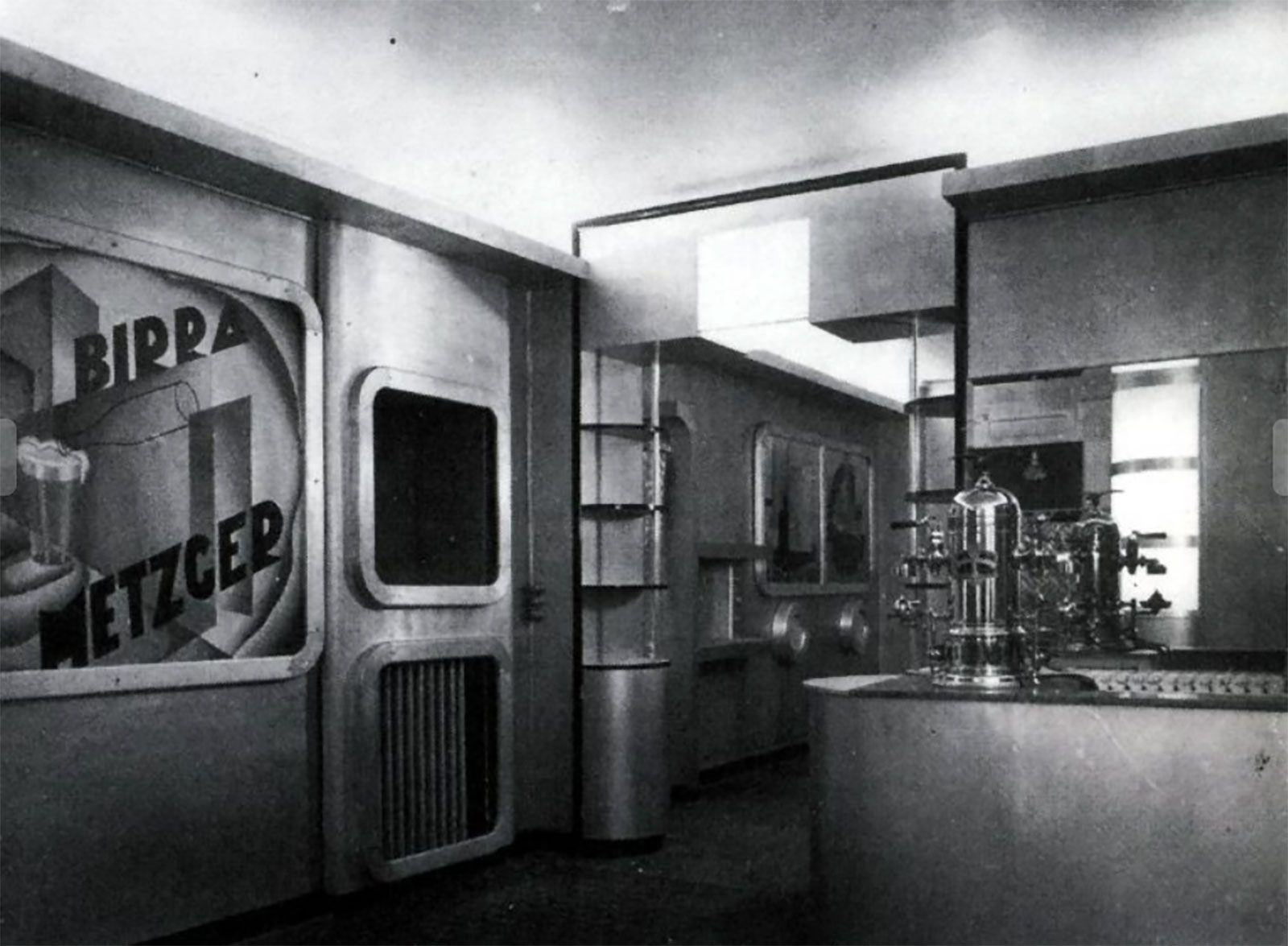

“SantoPalato”: the first Italian Futurists restaurant in Turin

“SantoPalato”: the first Italian Futurists restaurant in Turin

“SantoPalato”: in “Via Vanchiglia” in Turin, the first Italian Futurists restaurant

“SantoPalato”: in “Via Vanchiglia” in Turin, the first Italian Futurists restaurant

Futurist Cooking Guide

- An original harmony of the table (crystal ware, crockery and glassware, decoration) with the flavors and colors of the dishes.

- Utter originality in the dishes.

- The invention of flexible flavorful combinations (edible plastic complex), whose original harmony of form and color feeds the eyes and awakens the imagination before tempting the lips.

- The abolition of knife and fork in favor of flexible combinations that can deliver prelabial tactile enjoyment.

- The use of the art of perfumery to enhance taste. Each dish must be preceded by a perfume that will be removed from the table using fans.

- A limited use of music in the intervals between one dish and the next, so as not to distract the sensitivity of the tongue and the palate and serves to eliminate the flavor enjoyed, restoring a clean slate for tasting.

- Abolition of oratory and politics at the table.

- Measured use of poetry and music as unexpected ingredients to awaken the flavors of a given dish with their sensual intensity.

- Rapid presentation between one dish and the next, before the nostrils and the eyes of the dinner guests, of the few dishes that they will eat, and others that they will not, to facilitate curiosity, surprise, and imagination.

- The creation of simultaneous and changing morsels that contain ten, twenty flavors to be tasted in a few moments. These morsels will also serve the analog function […] of summarizing an entire area of life, the course of a love affair, or an entire voyage to the Far East.

- A supply of scientific tools in the kitchen: ozone machines that will impart the scent of ozone to liquids and dishes; lamps to emit ultraviolet rays; electrolyzers to decompose extracted juices etc. in order to use a known product to achieve a new product with new properties; colloidal mills that can be used to pulverize flours, dried fruit and nuts, spices, etc.; distilling devices using ordinary pressure or a vacuum, centrifuge autoclaves, dialysis machines. The use of this equipment must be scientific, avoiding the error of allowing dishes to cook in steam pressure cookers, which leads to the destruction of active substances (vitamins, etc.) due to the high temperatures. Chemical indicators will check if the sauce is acidic or basic and will serve to correct any errors that may occur: lack of salt, too much vinegar, too much pepper, too sweet.

From “The Futurist Cookbook” by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti