Azioni povere with Jannis Kounellis

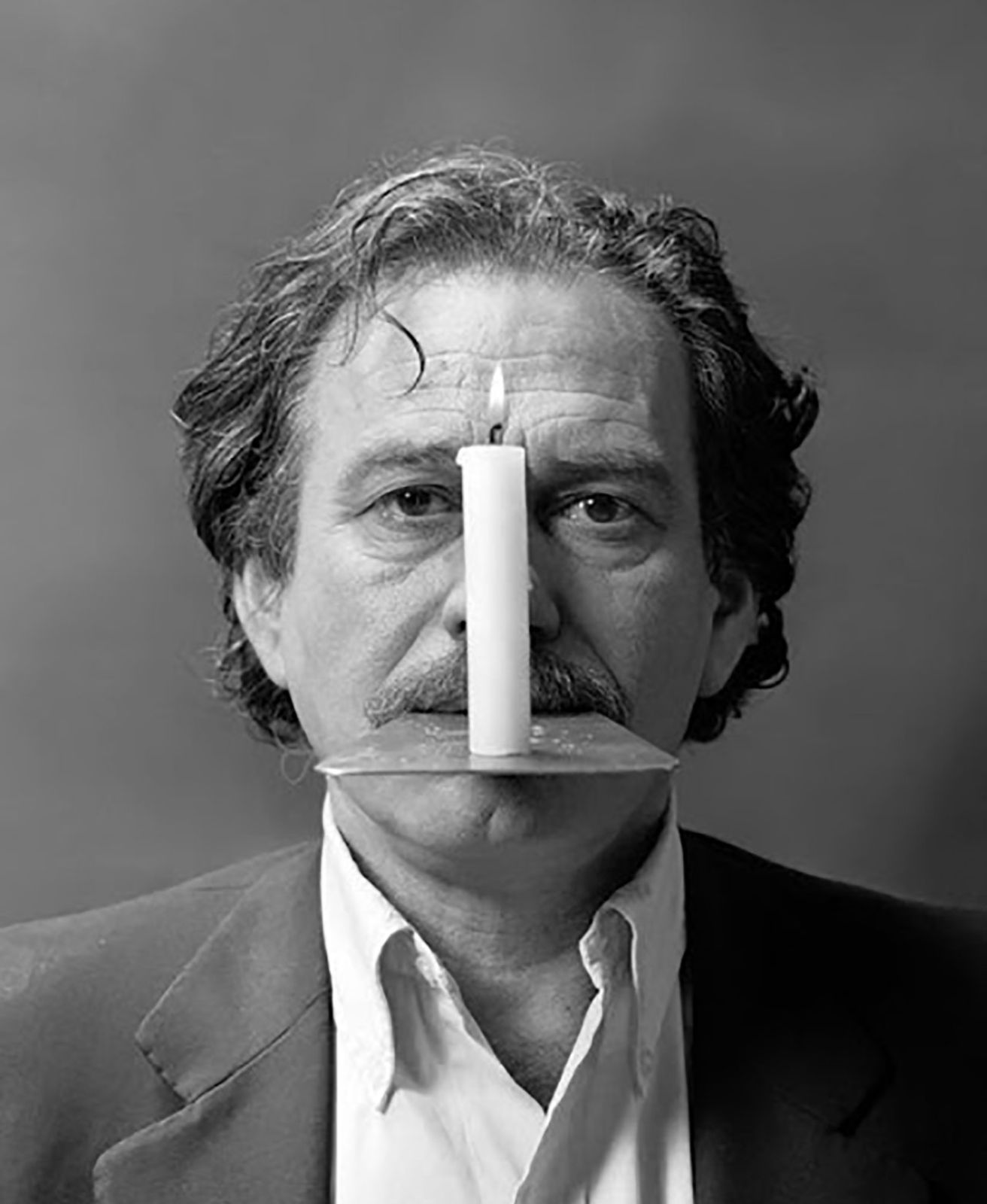

Germano Celant, Arte Povera: Notes on a Guerrilla War, published in Flash Art n. 5, 1967. Copyright Flash Art Archive

“If you take drama away from form you are left with formalism. Without drama, art becomes merely an industrial affair”. Leading figure of Arte Povera Jannis Kounellis is perhaps the most prolific representative of the movement. His practice, saturated by both ephemeral work as well as the creation of material objects, perfectly exemplified the radical age of Arte Povera in which the work of art existed in rejection of the representative form. Instances of ephemeral participatory works and happenings were provoked by the desire to promote individual subjectivity, to blur the lines between the spectator and the art.

The origins of “Arte Povera” lie within the performative. As Kounellis once said it himself, the term was born in the theatre, “connected with [Jerzy] Grotowski’s idea of a teatro povero.”. Its founder Germano Celant first met Jannis Kounellis as a young curator at the age of 23. The essential idea behind the Teatro Povero was a rejection of all that was deemed unessential within the theatrical practice. Grotowski’s theatre was to be reduced to the bare primary entities, the audience and the performer. Similarly, a group of artists dispersed between the major art hubs in Italy were independently adapting to a similar practice within the visual arts. In September of 1967 Celant published an essay for the exhibition Arte Povera – Im Spazio at the Galleria La Bertesca in Genoa. His efforts to contextualise the art practice he witnessed during the time lasted in the legacy of his term “Arte Povera” which to this day remains to be one of the most influential European art movements.

Translated the term refers to “poor art”: visual art forms that favoured simple materials, as well as simple gestures. At the time a radical subversion, the artists indirectly and directly rejected the institution, the rich and the traditional forms of art-making. In some ways, the actions of the Arte Povera artist existed in response to the growing commodification of art, represented through the rise of Pop Art in Europe. As an absolute counter movement, Pop Art spoke to the maintenance of capitalistic structures in the economy, enhancing the language of commodification and adapting visual art practices that mirror techniques within mass industrial production. The interventions of Arte Povera artists represented the exact opposite actions: “taking away, eliminating, downgrading things to a minimum, impoverishing signs” in the words of Celant, “to reduce them to their archetypes”.

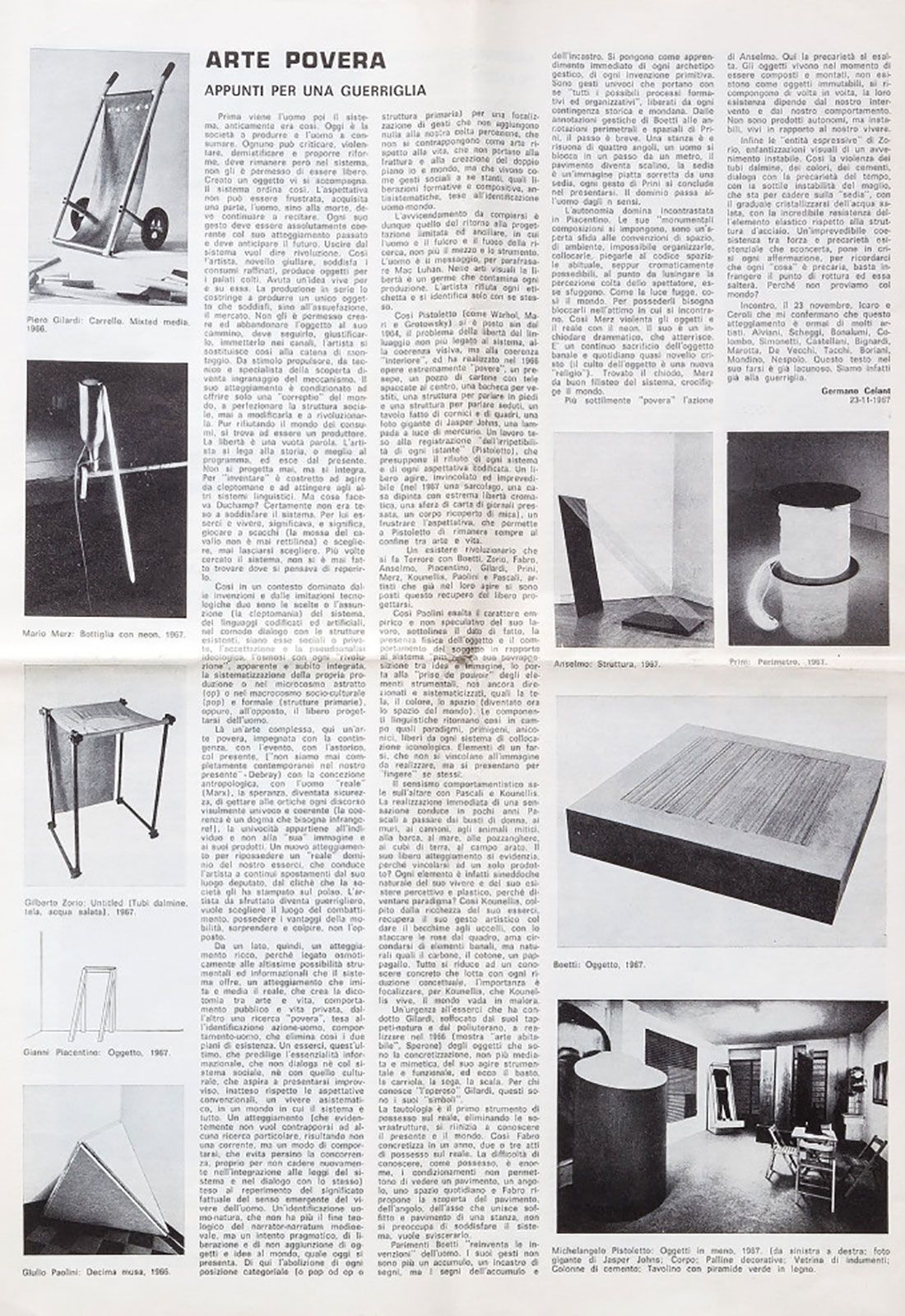

Michelangelo Pistoletto, The Minus Objects, 1966. Photography by Bressa

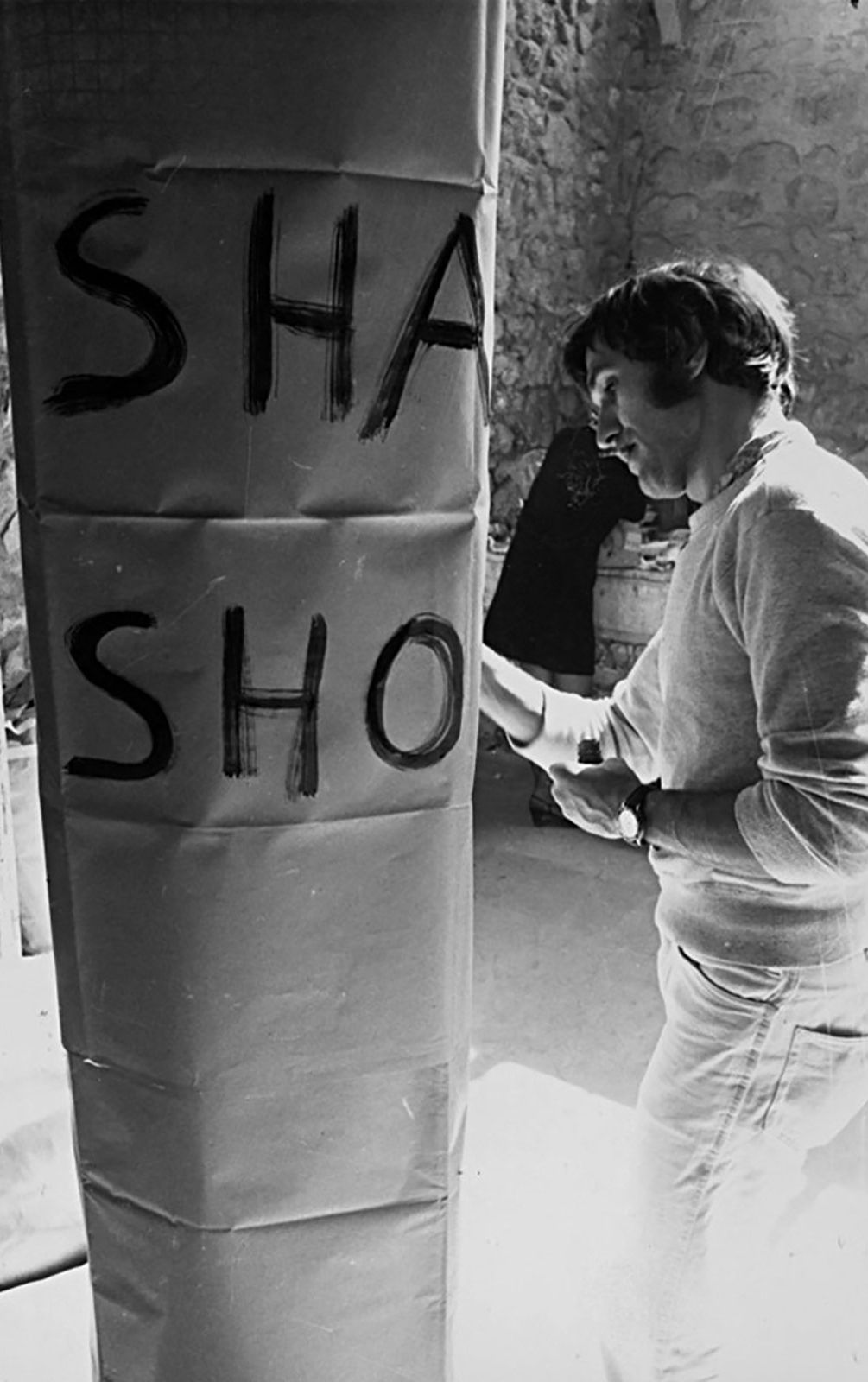

Alighiero Boetti working on Shaman-Showman at Arte Povera, 1968. Photo by Bruno Manconi. Courtesy of Archivo Lia Rumma.

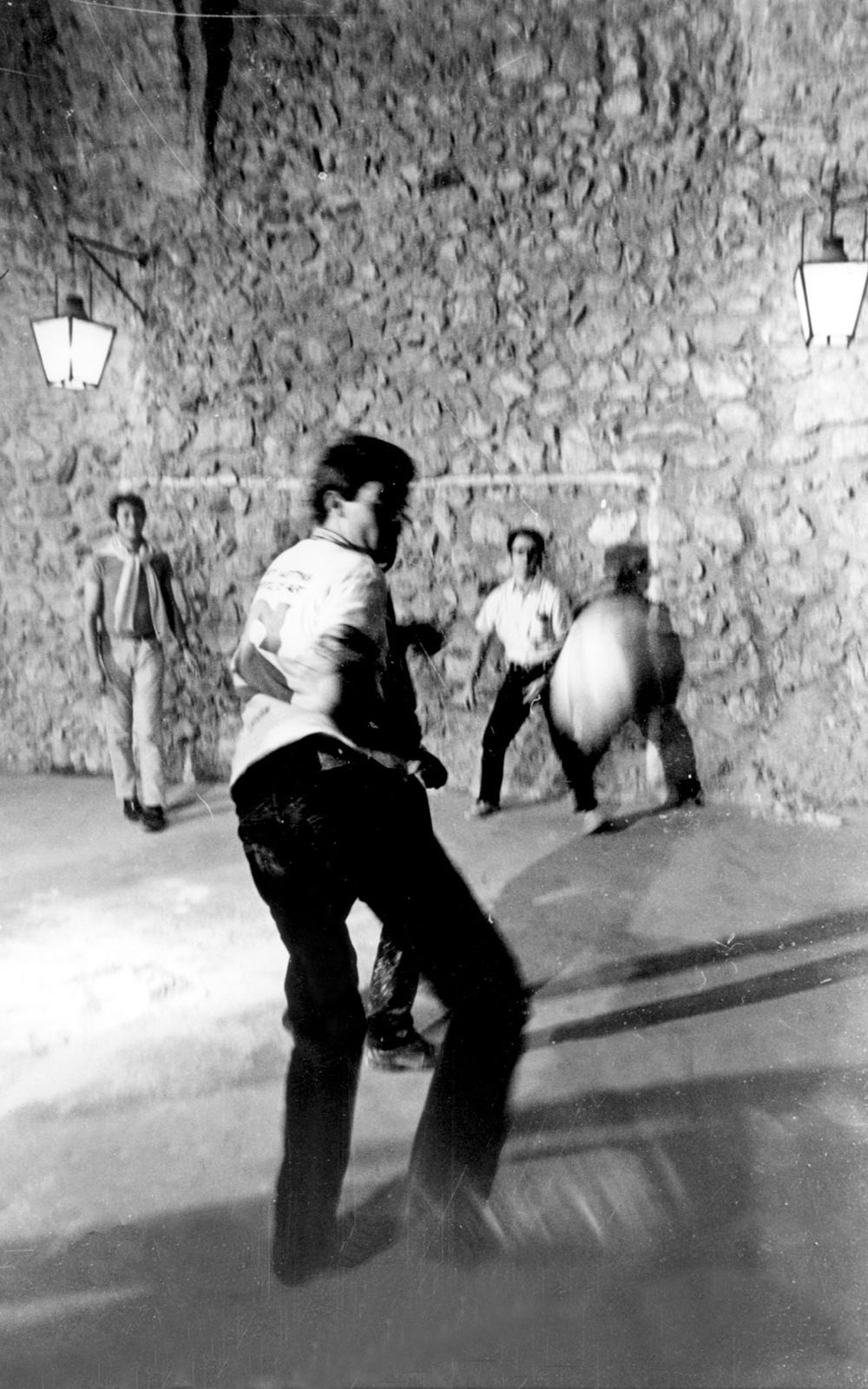

Richard Long, Paolo Icaro, and Francesco Gozzano playing football in the Arsenale. Photo by Bruno Manconi. Courtesy of Archivo Lia Rumma.

While material and object are key concepts within the movement, Arte Povera artists were interested in activating the objects through action, presence and participation. It is important to note that the term did not describe a specific art form or a specific group of artists that were organised like a collective. It loosely referred to particular exhibitions and artworks being created at the time, rejecting the normative art terminology such as “Conceptual Art”, “Landscape Art”, “Performance Art” or “Process Art”. Happenings such as Arte povera più azioni povere, a three- day event curated by Celant in 1968 shaped the way the movement was perceived and is remembered as one of its founding moments. Gathered in Amalfi, a group of artists followed the invitation of Marcello and Lia Rumma who asked Celant to curate an event that would redefine the “exhibition-happening”. It is at this moment where the attention within the group shifts from the object toward performative and ephemeral practices. Overall, around twenty artists are included in the event: Carmine Ableo, Giovanni Anselmo, Alighiero e Boetti, Anne Marie Sauzeau Boetti, Jan Dibbets, Paolo Icaro, Jannis Kounellis, Richard Long, Gino Marotta, Mario Merz, Marisa Merz, Pino Pascali, Michelangelo Pistoletto, Emilio Prini and Gilberto Zorio.

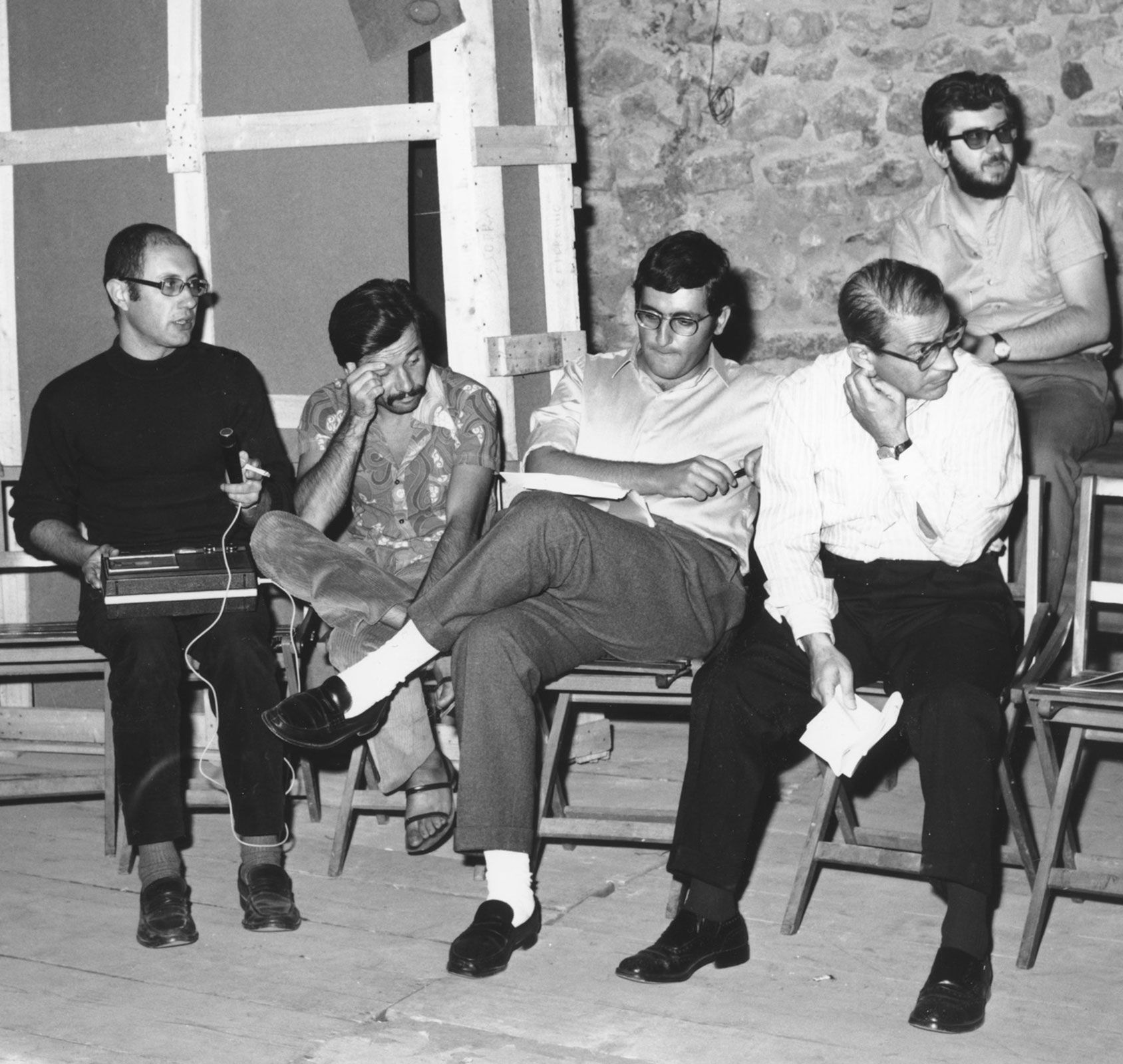

The assembly during the exhibition Arte Povera + Azioni Povere, Amalfi, Italy, 1968. From left: Tommaso Trini, Achille Bonito Oliva, Germano Celant, Filiberto Menna, Marcello Rumma (top right). Courtesy of Archivio Lia Rumma, Naples.

While some of the artist, such as Michelangelo Pistoletto, have over the course of time dedicated themselves to a signature element, others such as Jannis Kounellis continued to transform into the 21st century, experimenting with various subject and media. The greek-born artist transferred from Piraeus in Greece to Rome in 1956, following the Second World War and Greek Civil War. For Kounellis, identity and origin were connected to “an opinion” rather than an actual place. His relationship with both Greece and Italy can be contextualised within a Mediterranean identity prevalent with many artist of the region. When he attended Rome’s “Accademia di Belle Arti”, the artist was explicitly fascinated with the works of avant-garde Italians such as Alberto Burri or Piero Manzoni. For first solo exhibition, Kounellis presented a series of plain white canvasses which displayed stencilled letters and numbers. Potentially inspired by Manzoni’s radically minimalistic white paintings the work represented a vitality of signs, ready to be activated and to transcend from the plain canvas. At exhibition openings Kounellis would often “perform” these paintings in a suit made out of white linen canvas, calling the phonetic poems.

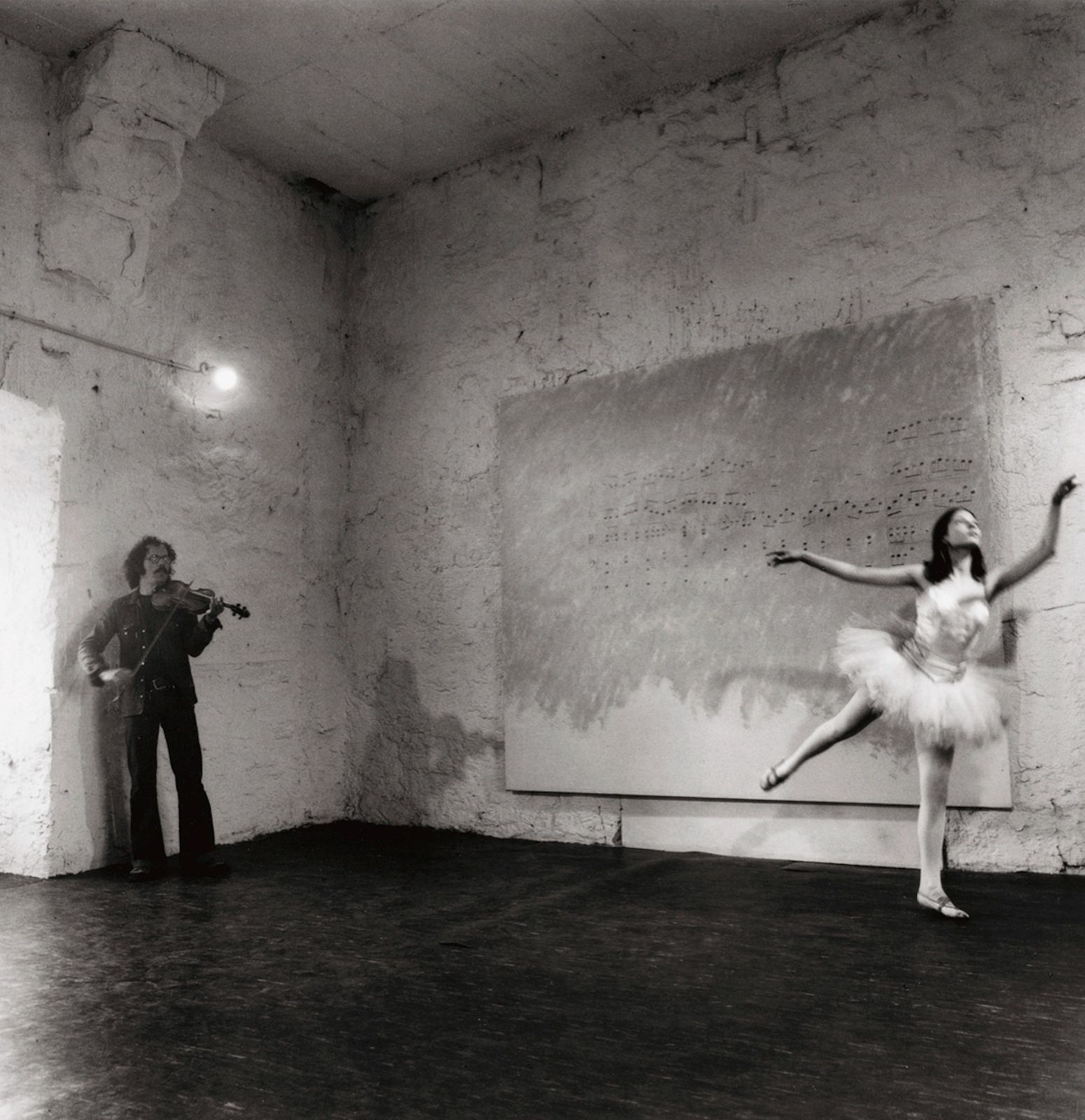

Presentation of Jannis Kounellis Da inventare sul posto (To Invent on the Spot), 1972 at Documenta V, Kassel 1972, 1972

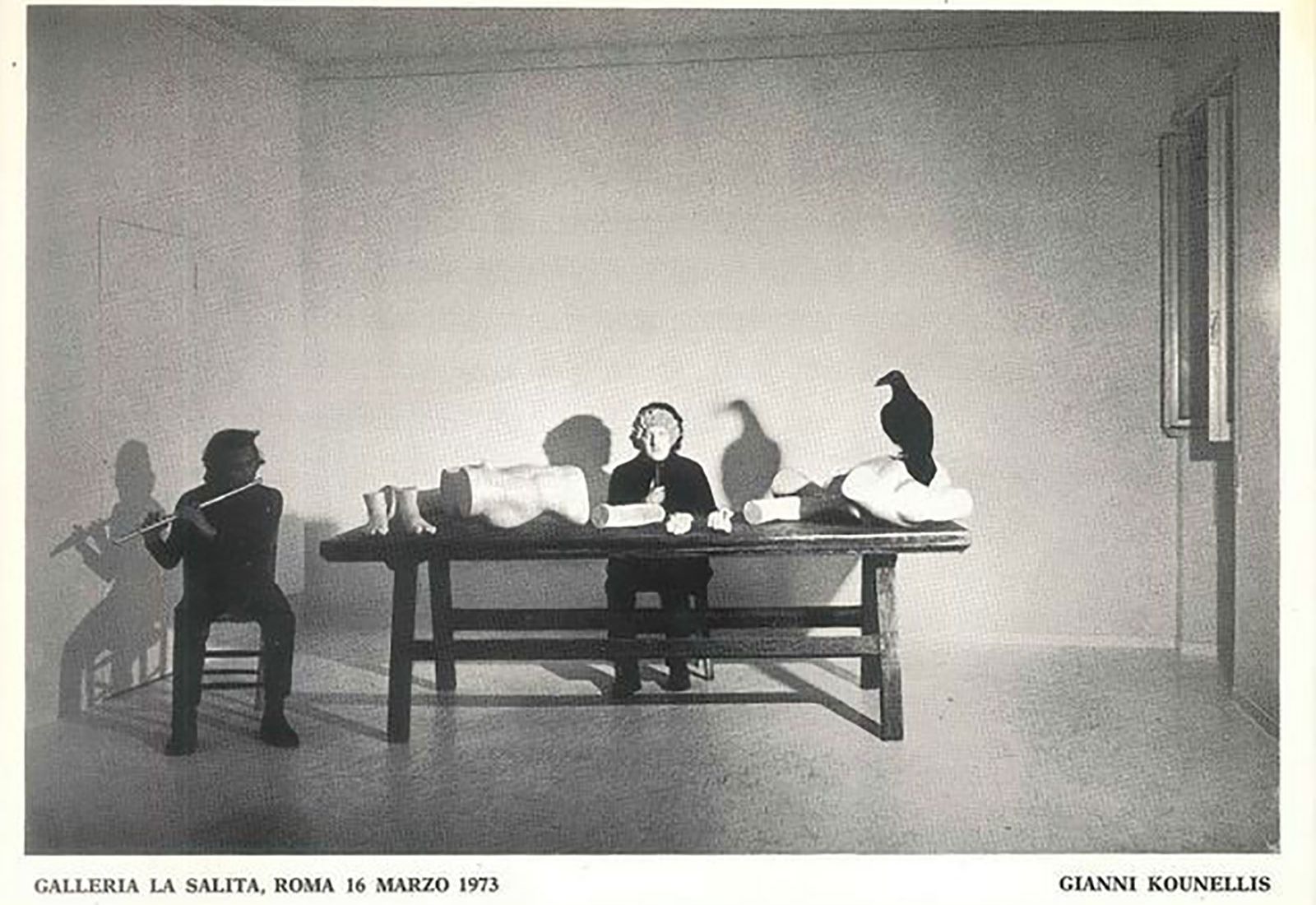

Kounellis Performance at Galleria La Salita, 1973

Throughout his artistic career, Kounellis was able to push the boundaries of visual art practices while taking part in the discovery of a new material culture informed by Arte Povera. His performative oeuvre is characterised by an introduction or participation of the body which reexamined the possibilities of art-making by synthesising the performed with historical and contemporary references. In the acclaimed work Da inventare sul posto (To Invent on the Spot), 1972 for example, the artist fully removed himself as a participant or even author of the work. Framing an abstract painting of his that features loose pink brushstrokes displaying a passage of Igor Stravinsky’s score for La Pulcinella (1920), is a violinist and a ballerina, standing on both ends of the painting. While the violinist plays a short musical sequence, the dancer improvised a choreography “on the spot”. Each iteration of the performance becomes unique.

Another famous performance of Kounellis is the staging at Galleria La Salita in 1973 where Kounellis himself sat behind a large desk covered in white scattered fragments of a seemingly ancient sculpture. Sat on top of the sculpture’s bust next to the artist, is a stuffed black crow, his head turned to the right towards a musician sitting next to the table playing a melody by Mozart on the flute. Kounellis, in the meantime, is covering his face with the mask of Apollo. This stage- like setting is meant to evoke a sense of sacrifice of a fragmented body that can only be resurrected through the presence of the crow, symbol of death. Kounellis noted that the work is not meant to symbolise reincarnation, but moreover the reincarnation of ideas and aims. Here the sourcing of the material and its staging is quite similar to the setting of a theatre stage; each “prop” is chosen carefully as it symbolises an element of the story narrated on stage. The table stands as an emblem for everyday life, the place where everyone assembles each day, where life takes place. Next, the musician playing Mozart as a symbol for enlightenment, juxtaposed with the presence of the history (the antique), Nature (crow as death) as well as mythology (Apollo).

Presentation of Jannis Kounellis Da inventare sul posto (To Invent on the Spot), 1972 at Documenta V, Kassel 1972, 1972

Presentation of Jannis Kounellis Da inventare sul posto (To Invent on the Spot), 1972 at Documenta V, Kassel 1972, 1972

At the Roman L’Attico gallery in 1969, Kounellis staged one of his most famous performances, Untitled (12 horses), 1969. As suggested by the title, the work consisted of the placement of twelve live horses tethered alongside the walls of the gallery. Its straightforward idea was developed by Kounellis in the interest to explore the structural identity of the space: “What interested me”, the artist said, “was that the horse was part of the wall”. Later in 2015 at the re- staging of the exhibition at Gavin Brown’s Enterprise in New York, the gallery owner Gavin Browner proclaimed: “I don’t think it’s about anything”, claiming that the coverage and reaction of the show itself would reveal the meaning of the work.

The horses evoke an incomparable presence, a tension that expresses awe and fear at the same time. The visitor may not be accustomed to encountering horses in a gallery space, and in respect for the animal will turn quiet, walking throughout the exhibition with care, keeping a distance from the horses. Similar to a space with highly valuable art, the typical gallery or museum visitor will adapt to a lower speaking voice and avoid to approach the walls too closely. The utilisation of live animals was not new; in fact it played a vital role in the movement’s participatory element and new materiality that mirrored the raw and the natural. Artists such as Paolo Calzolari also often featured living animals in their installation. Overall this work has been re-staged six times and remains a critically essential work within the oeuvre of Arte Povera. Small in gesture, simple in arrangement, this intervention into the gallery space exemplifies the work’s aim to humbly interfere while subverting radically.