Alexander Calder: Master of movement

“Just as one can compose colors, or forms, so one can compose motions.”

Alexander Calder

It is difficult to escape the sensual spell of Calder’s signature mobile sculptures. Their recognisable nature provokes fascination and wonder about gravity, craft and form. With a background in mechanical engineering, the artist developed an unprecedented understanding of the interplay between geometric structures, biomorphic forms and contours that evoke surrealistic imagery that come to life through three-dimensional engineering. The confrontation between viewer and sculpture established Calder’s legacy as one that almost singularly dominated the market landscape of American kinetic and modernist sculpture during his lifetime. The recently inaugurated Calder Archive of the Calder Foundation provides an extraordinary insight into the artist’s remarkable life and bibliography.

Calder and his sister, Margaret “Peggy” Calder, Oracle, Arizona, 1906 via © 2021 Calder Foundation, New York.

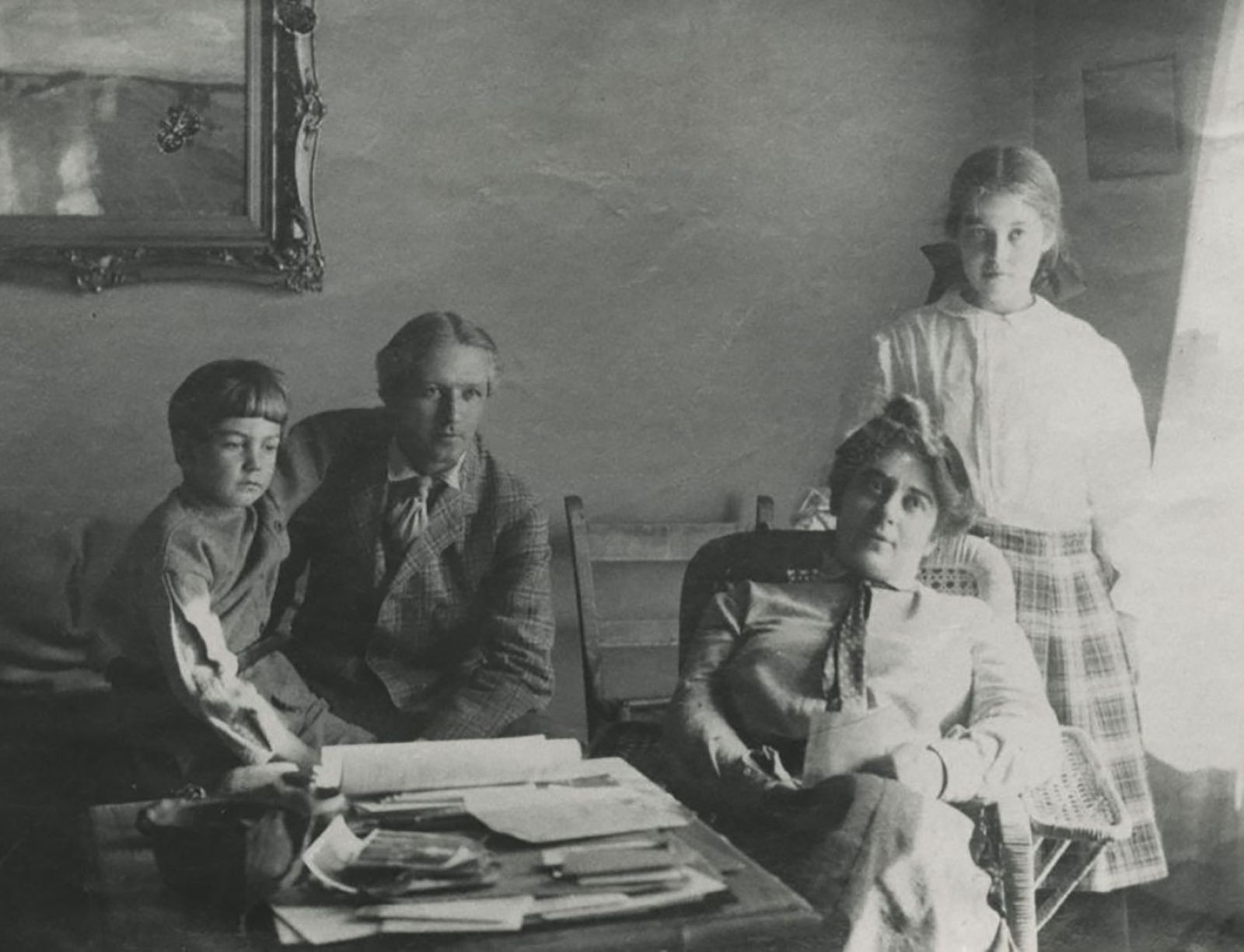

The Calders at home in Pasadena, c. 1908 via © 2021 Calder Foundation, New York.

Calder in front of Alexander Stirling Calder’s Fountain of Energy, Panama-Pacific International Exposition, San Francisco, 1915 via © 2021 Calder Foundation, New York.

“To an engineer, good enough means perfect. With an artist, there’s no such thing as perfect.”

Born in 1898 in a small town in Lawnton, Pennsylvania, Alexander Calder grandfather and father were both well-known sculptors and his mother a professional portrait artist. With this early artistic influence and creative environment, Calder created artworks throughout his childhood, experimenting with sheets of brass, for example. During the artist’s high school years, the Calder family relocated to both California and New York, where his parents provided him with his own studio space to accelerate his creativity. Despite this encouragement, his parents did not want him to become an artist, and Calder consequently decided to study mechanical engineering. About this decision, the artist was quoted saying: “I was not very sure what this term meant, but I thought I’d better adopt it”, “I wanted to be an engineer because some guy I rather liked was a mechanical engineer, that’s all”.

After receiving his degree, the artist held various jobs, including being a hydraulic engineer or working as a mechanic on a passenger ship in 1922. After taking a job back on land, as a timekeeper at a logging camp in Aberdeen, Washington, Calder was inspired by the mountain landscape, and his passion for the arts began to reignite. In New York, he enrolled at the Art Students League, where he studied alongside artists such as George Luks. After relocating to Paris in 1926, Calder created some of his leitmotifs featuring key subjects such as the circus.

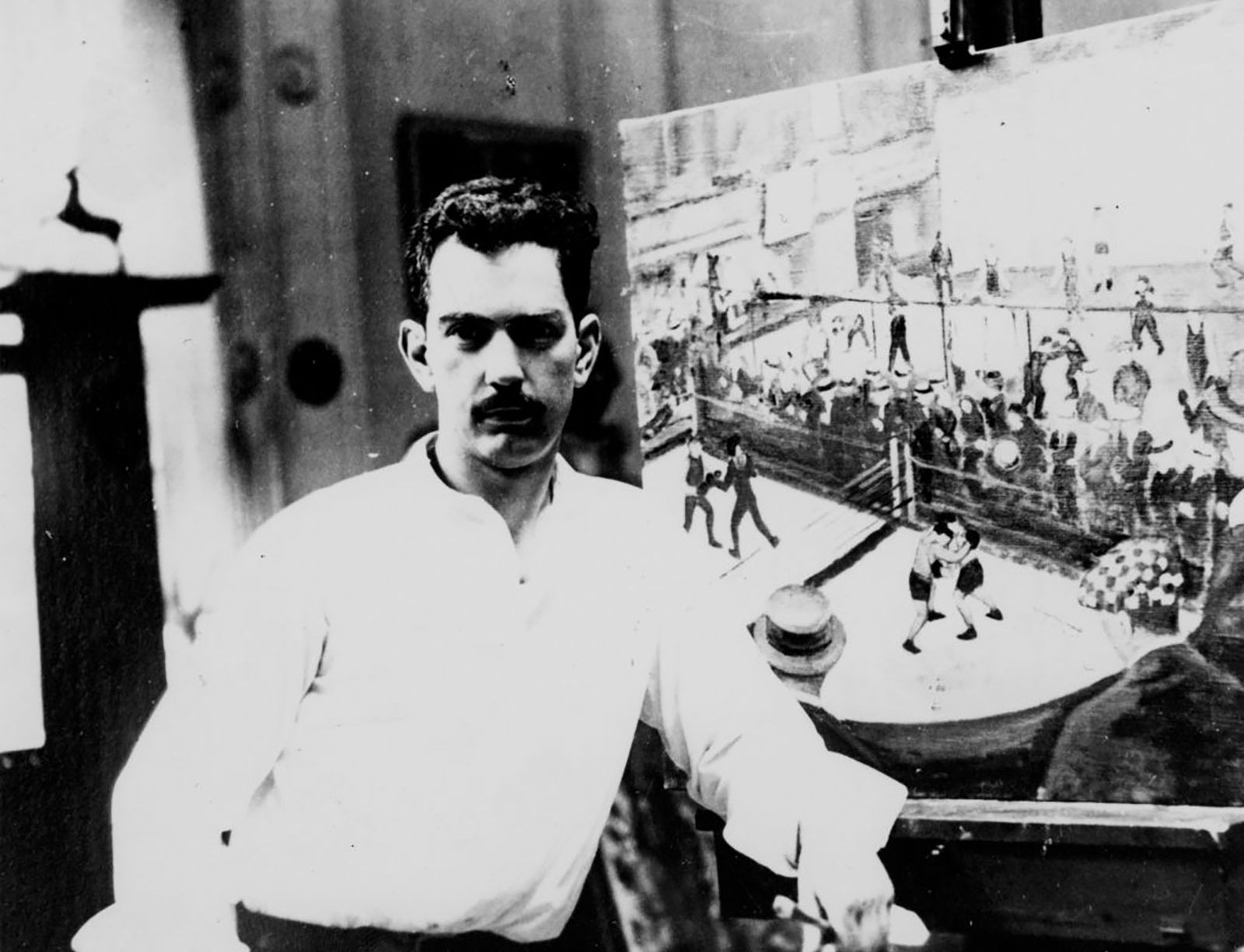

Calder photographed in front of his painting, Untitled (Boxing at the Madison Square Garden Gymnasium), New York, 1924 via © 2021 Calder Foundation, New York.

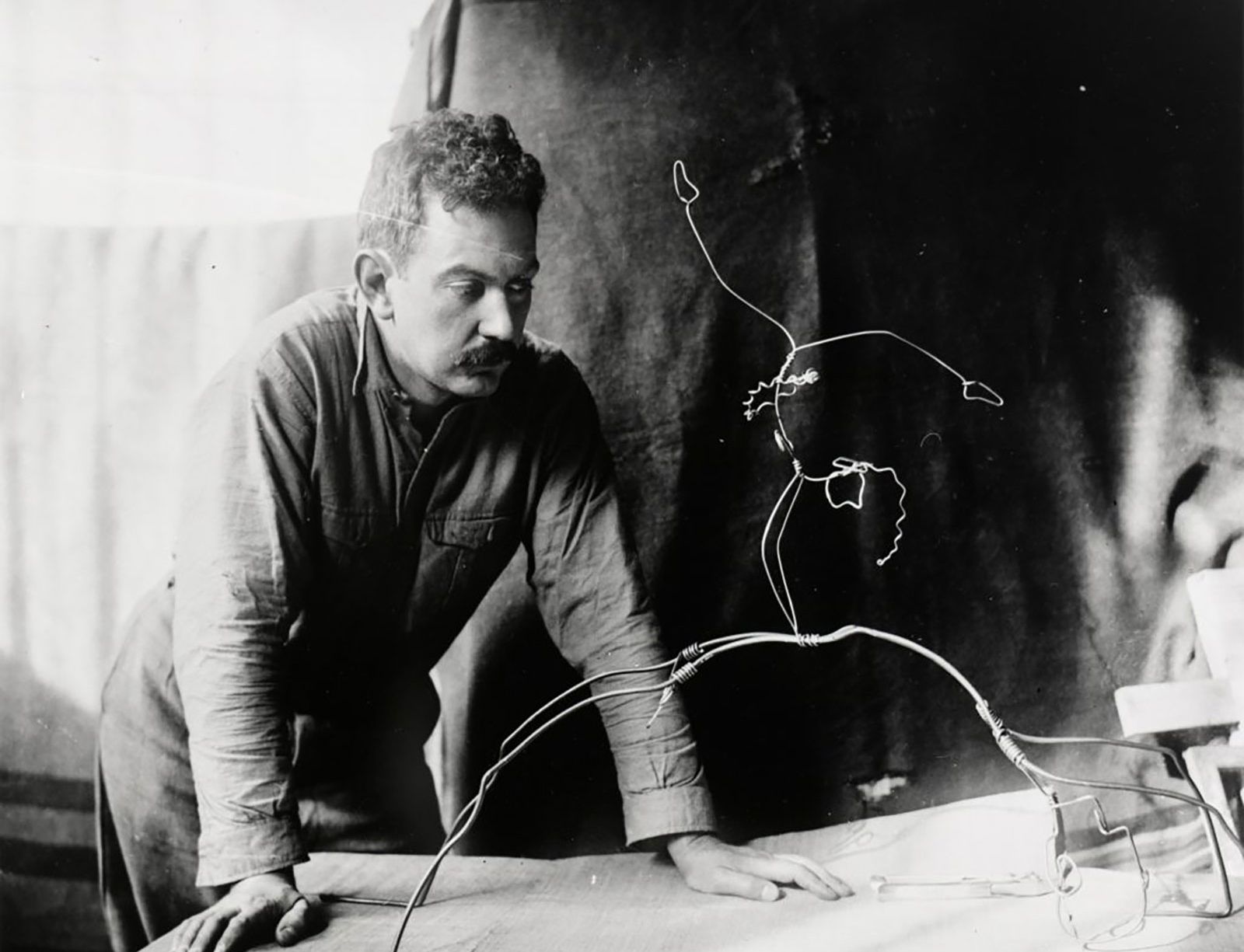

Calder with Acrobats, 1929 via © 2021 Calder Foundation, New York.

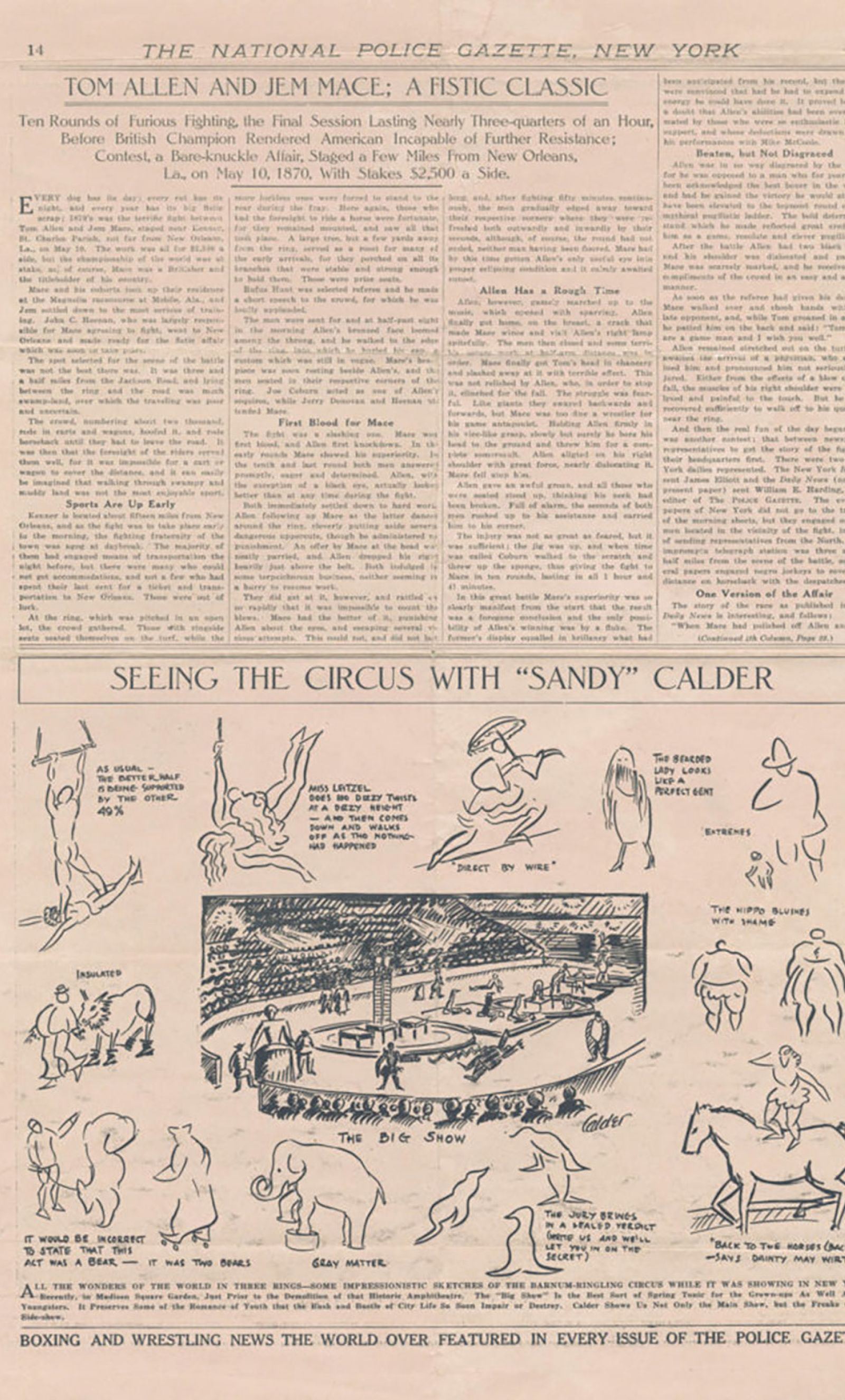

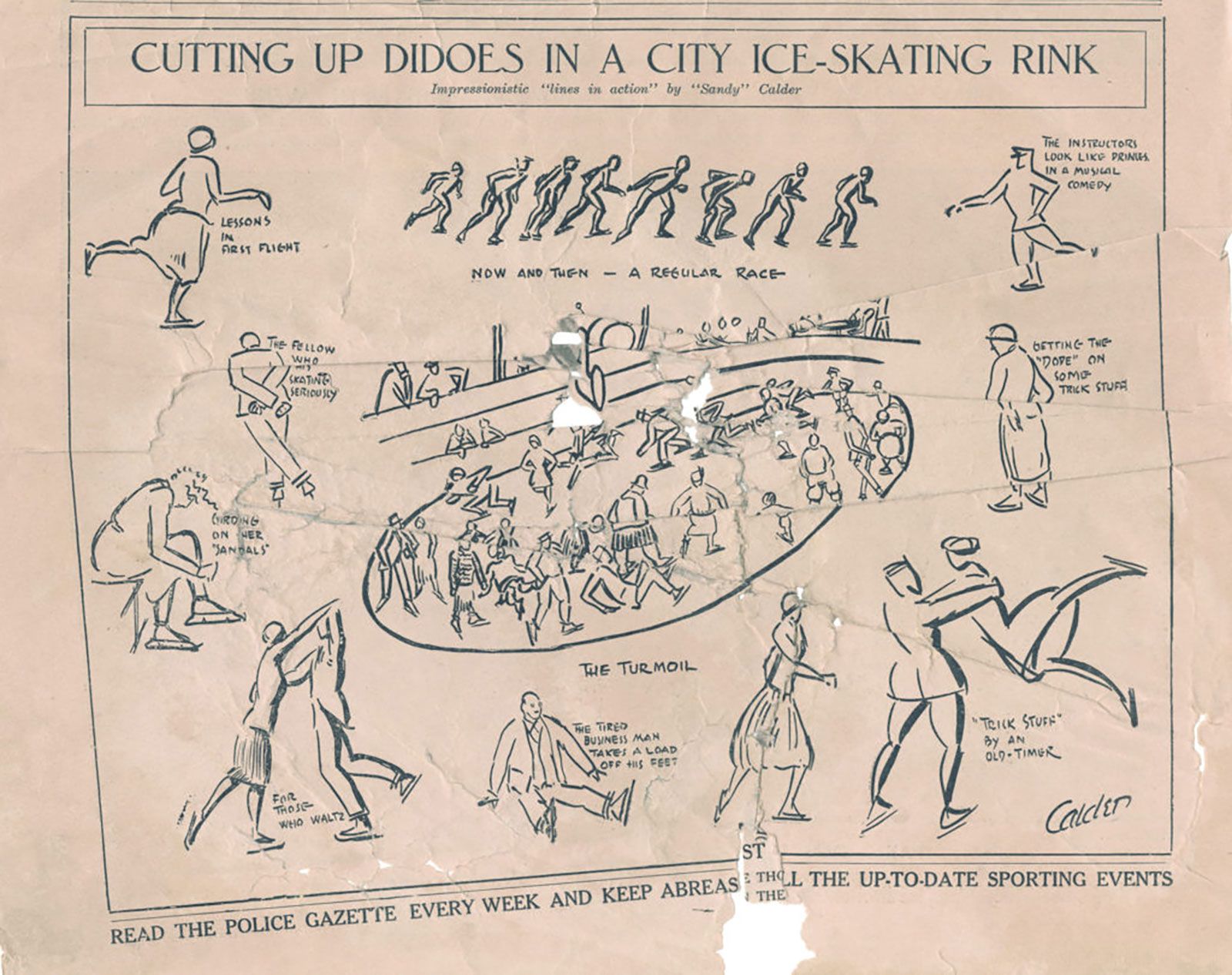

“On a Sketching Stroll Through New York’s Central Park.” National Police Gazette, 17 October 1925. via © 2021 Calder Foundation, New York.

“On a Sketching Stroll Through New York’s Central Park.” National Police Gazette, 17 October 1925. via © 2021 Calder Foundation, New York.

“ Oh, these are stylized silhouettes, but astonishing in their miniature resemblance, obtained by means of luck, iron wire, spools, corks, elastics… A stroke of the brush, a stroke of the knife, of this, of that; these are the skillful marks that reconstruct the individuals that we see at the circus.”

A year prior, back in New York, Calder worked for the Police Gazette illustrating events and sketching scenes of the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus. Additionally the artist spend lengthy times drawing hundreds of animals at the Bronx and Central Park zoos.

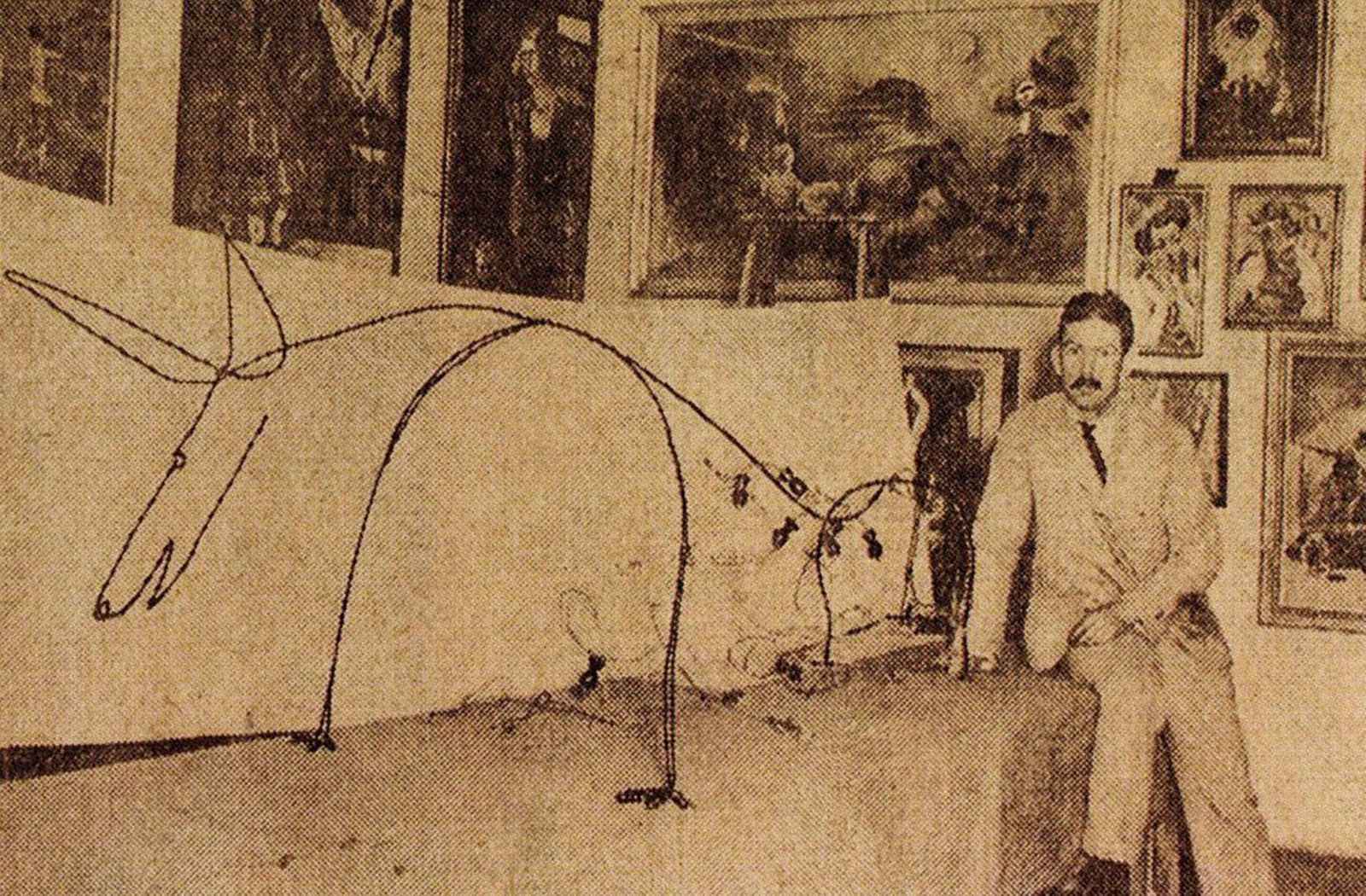

Alexander Calder, Romulus and Remus, 1928.

Calder with Romulus and Remus, Twelfth Annual Exhibition of The Society of Independent Artists, Waldorf-Astoria, New York, 1928 via © 2021 Calder Foundation.

“The first inspiration I ever had was the cosmos, the planetary system.”

While in Paris, Calder frequented amongst European avant-garde artists, befriending prominent figures such as Fernand Léger, Marcel Duchamp and Jean Arp. In 1931 the artist’s first exhibition was held at Galerie Percier, for which Léger wrote the preface of the show’s catalogue. In 1933 Calder and his wife return to the US. The next decades the artist spent travelling and rejected from joining the troops during the Second World War, he continued to develop his sculptural practice due to the scarcity of aluminium during the war, returning to carved wood as a medium.

Calder arriving with a bundle of his wire sculptures to present at Galerie Neumann-Nierendorf, Berlin, 1929 via © 2021 Calder Foundation, New York.

Calder assembling Five Rods and Nine Discs (1936), Roxbury, summer 1938 Photograph by Herbert Matter © Calder Foundation, New York via © 2021 Calder Foundation, New York.

Calder assembling Five Rods and Nine Discs (1936), Roxbury, summer 1938 Photograph by Herbert Matter © Calder Foundation, New York via © 2021 Calder Foundation, New York.

Calder assembling Jacaranda (1949) at the exhibition Calder, New Gallery, Charles Hayden Memorial Library, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, 1950 via © 2021 Calder Foundation, New York.

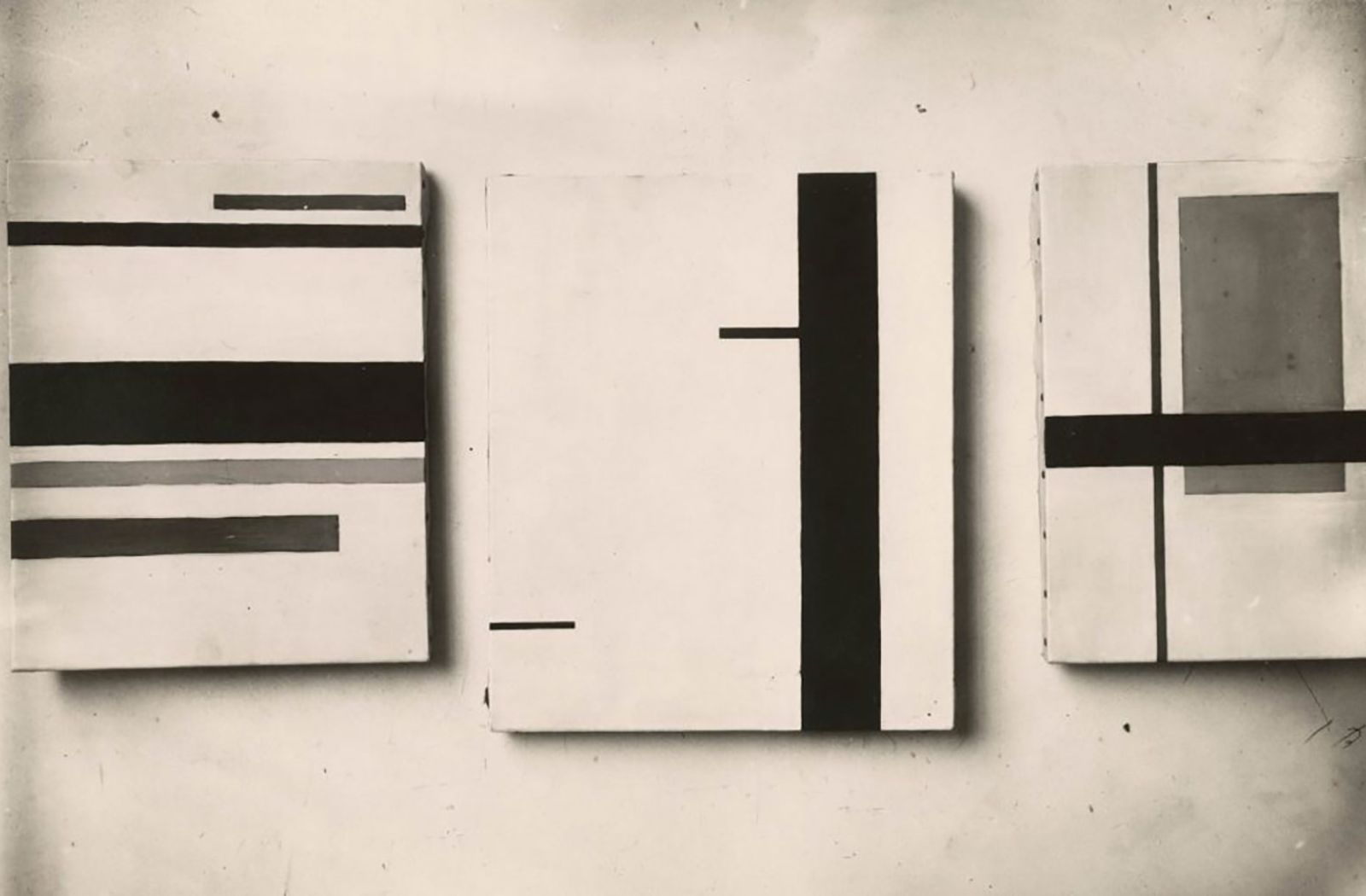

Alexander Calder’s 1930 oil paintings, 1931 Photograph by Marc Vaux © Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Centre Georges Pompidou, Marc Vaux Collection.

“I paint with shapes.”

Calder never considered himself a painter. His painterly body of work exposes artistic studies that explore geometric forms and bold colours. These two-dimensional works investigated composition on a flat surface, exploring colour and line. In addition to his prominent sculptural body, Calder painted throughout his artistic career. After a period of drawing in the 1920s in New York, the artist’s painterly practice developed into pure abstraction. Protesting the Vietnam war later in his career, in the late 1960s, Calder developed his print practice producing posters.

“If you can imagine a thing, conjure it up in space then you can make it… The universe is real but you can’t see it. You have to imagine it. Then you can be realistic about reproducing it.”

Detail of: Alexander Calder, Untitled, 1930.

Calder was famously inspired by a visit to the studio of Dutch painter Piet Mondrian in 1930. Following this seminal encounter, Calder’s practice shifted towards abstraction, adapting compositions and innovative actuations of space. During those years, the artist invented the first kinetic sculpture that he referred to as “mobile”, a term first coined by Marcel Duchamp. This terminology encompasses both “motive” and “motion”. His earliest experimentations included mechanical motors, which the artist quickly abandoned, devoting the aura of his works to the interplay with natural forces such as humidity, light, air currents and human interaction.

“It was a very exciting room. Light came in from the left and from the right, and on the solid wall between the windows there were experimental stunts with colored rectangles of cardboard tacked on. Even the victrola, which had been some muddy color, was painted red. I suggested to Mondrian that perhaps it would be fun to make these rectangles oscillate. And he, with a very serious countenance, said: “No, it is not necessary, my painting is already very fast.” This one visit gave me a shock that started things. Though I had heard the word “modern” before, I did not consciously know or feel the term “abstract.” So now, at thirty-two, I wanted to paint and work in the abstract. And for two weeks or so, I painted very modest abstractions. At the end of this, I reverted to plastic work which was still abstract.”

Alexander Calder, Untitled, 1934.

Alexander Calder, Tightrope, 1936.

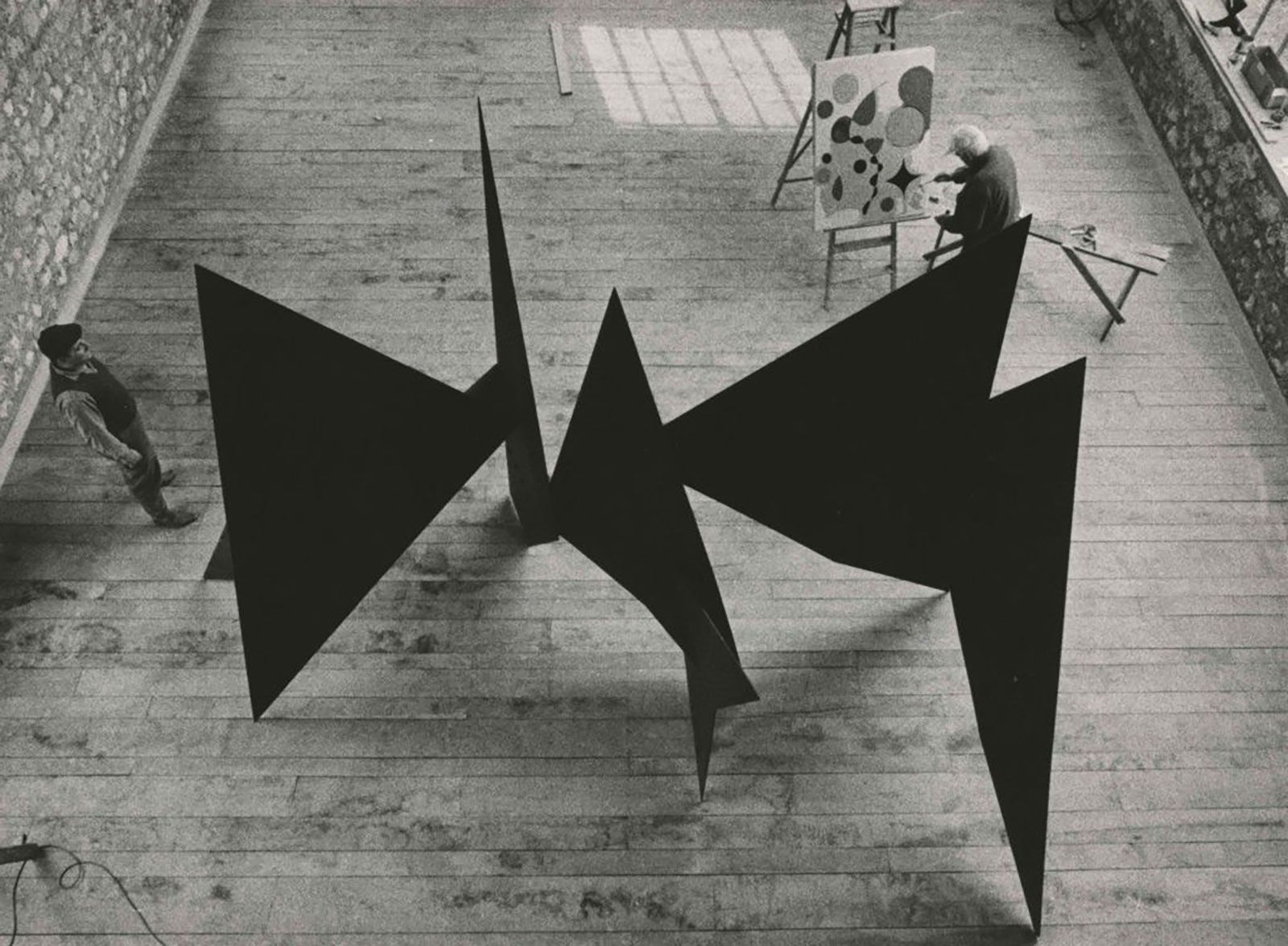

In 1963 Calder created series of works that included some of his most monumental sculptures. The artist created his first outdoor sculptures as early as 1934 in his Roxbury, Connecticut studio. Within his sculptural oeuvre, the large-scale sculptures are constructed with the same materials and techniques as Calder’s smaller, fragile mobile structures. In the late 1930s after committing to work on a smaller scale, the artist’s devoted himself to the creation of his “maquettes”, which were later translated to monumental size.

These monumental works were undoubtedly inspired by his father’s and grandfather’s practice who worked as traditional sculptors. Specifically, Calder drew inspiration from traditional technique when seeking a way to enlarge his compositions that were drawn on craft paper and enlarged by using a grid system, staying in line with the exact specifications.

Calder painting Untitled with Les Triangles in the foreground, Le Carroi studio, Saché, 1963 Photograph by Ugo Mulas © Ugo Mulas Heirs via © 2021 Calder Foundation, New York.

Southern Cross, 1963 via © 2021 Calder Foundation, New York.

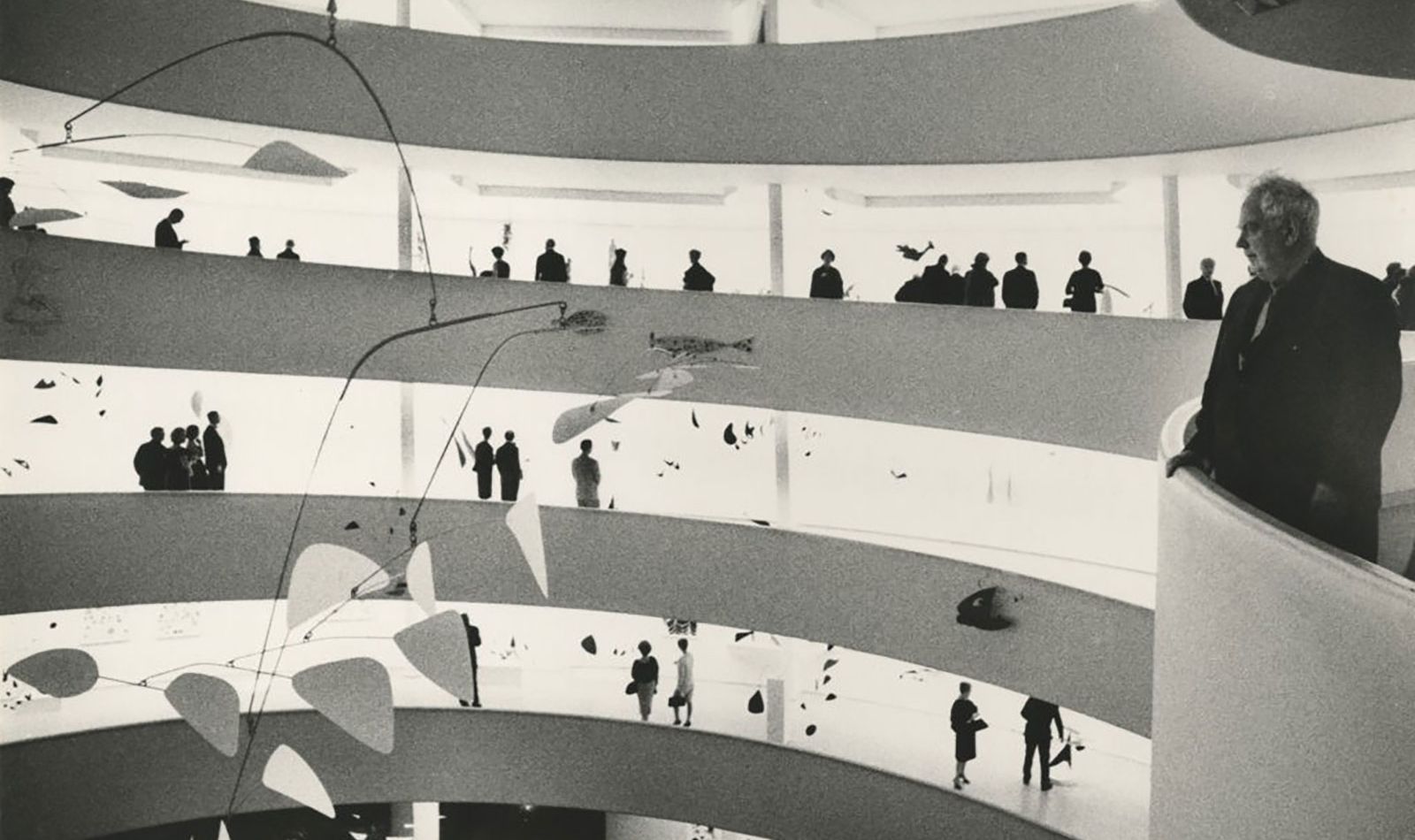

Calder at the opening preview for Alexander Calder: A Retrospective Exhibition, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, 1964 Photograph by Ugo Mulas © Ugo Mulas Heirs via © 2021 Calder Foundation, New York.

Calder at the installation of Calder, Musée National d’Art Moderne, Paris, 1965 Photograph by Gjon Mili via © 2021 Calder Foundation, New York.

Flamingo, 1973 via © 2021 Calder Foundation, New York.

In the years leading up to his death the artist would devote himself to the creation of public commissions that today, stand as landmarks marking a legacy of one of the most important American sculptors to date. Explore exhibition ephemera, videos, literature and a vast archive of imagery on the newly opened Calder Archive on the website of the Calder Foundation.